Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation for Low Back Pain

of Pregnancy: A Retrospective Case SeriesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Midwifery Womens Health 2006 (Jan); 51 (1): e7-10 ~ FULL TEXT

Anthony J. Lisi

University of Bridgeport College of Chiropractic.

anthony.lisi@med.va.gov

Low back pain is a common complaint in pregnancy, with a reported prevalence of 57% to 69% and incidence of 61%. Although such pain can result in significant disability, it has been shown that as few as 32% of women report symptoms to their prenatal provider, and only 25% of providers recommend treatment. Chiropractors sometimes manage low back pain in pregnant women; however, scarce data exist regarding such treatment. This retrospective case series was undertaken to describe the results of a group of pregnant women with low back pain who underwent chiropractic treatment including spinal manipulation. Seventeen cases met all inclusion criteria.

The overall group average Numerical Rating Scale pain score decreased from 5.9 (range 2-10) at initial presentation to 1.5 (range 0-5) at termination of care. Sixteen of 17 (94.1%) cases demonstrated clinically important improvement. The average time to initial clinically important pain relief was 4.5 (range 0-13) days after initial presentation, and the average number of visits undergone up to that point was 1.8 (range 1-5). No adverse effects were reported in any of the 17 cases. The results suggest that chiropractic treatment was safe in these cases and support the hypothesis that it may be effective for reducing pain intensity.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain is a very common complaint during pregnancy. European studies have reported the prevalence rate of low back pain during the 9 months of pregnancy to be from 46% to 76%. [1, 2] Recent US studies found prevalence rates of 57% and 69%. [3, 4]

The incidence of low back pain with an onset during pregnancy has been reported to be 61%. [2] It has been shown that among women with low back pain of pregnancy, 75% reported no low back pain before pregnancy. [4] In a study of women with chronic low back pain, up to 28% stated that their first episode of back pain occurred during a pregnancy. [5]

Like most cases of low back pain in general, the etiology of low back pain of pregnancy is not known. It has long been considered to be related to maternal weight gain and resulting biomechanical changes in the spine; however, epidemiologic data provide a conflicting picture. Several studies have found no relationship between onset of pain and gestational age, [2, 3, 5] and indeed, the onset of low back pain of pregnancy is often earlier than week 6 of pregnancy, with the largest proportion often between weeks 13 and 30. [2, 5] Increased lumbar lordosis is commonly considered a cause of low back pain in pregnancy. However, it has been shown that lumbar lordosis does not categorically increase in every pregnant woman; moreover, when lordosis does increase, it is not clearly related to severity of low back pain. [6-8]

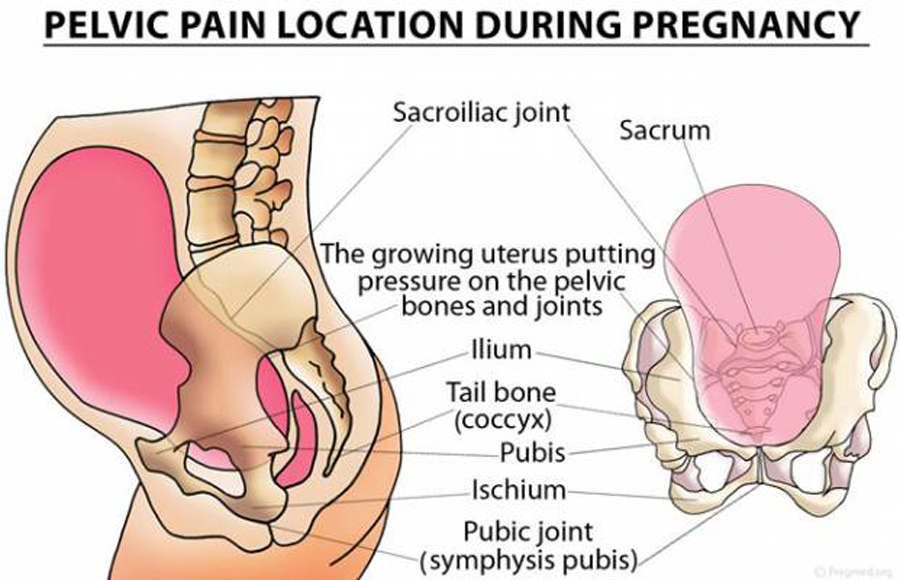

Increased joint laxity secondary to relaxin is a known phenomenon, but its relationship to onset of low back pain remains unclear. [9] However, one factor supported by preliminary work is that asymmetry of sacroiliac joint laxity, rather than absolute laxity alone, is related to low back pain of pregnancy. [10, 11]

In most instances, the average pain level is moderate, but severe pain has been reported in 15% of cases. [3, 4] Pain intensity often increases with duration and can result in significant disability. [2] Sleep disturbances have been reported by 49% to 58% of women and impaired daily living by 57% in women with low back pain of pregnancy. [3, 4]

Despite the apparent impact it has on women, many cases of low back pain of pregnancy go unreported to prenatal providers and/or untreated. Wang et al. found that just 32% of women reported their low back pain of pregnancy to their prenatal providers, and just 25% of these providers recommended a treatment.3 Skaggs et al. found that among women with low back pain of pregnancy, 80% thought that their providers had not offered treatment for their back pain. [4]

The clinical management of low back pain of pregnancy varies among prenatal providers, [2, 3] yet it seems clear that chiropractors are, at times, involved in the management of such cases. Chiropractors commonly manage low back pain and other musculoskeletal pain patients, [12] and although there are little clear data indicating what percentage of those patients are pregnant, a survey of US chiropractors reported 76% of respondents were involved in the management of pregnant women. [13] A recent population-based survey of Australian women found that 11% of women with low back pain of pregnancy underwent chiropractic treatment. [14] A survey of North Carolina certified nurse-midwives found that 93.9% of respondents recommend complementary and alternative medicine to their pregnant patients, and more than half of these recommended chiropractic treatment, mostly for low back pain of pregnancy. [15]

Table 1 Chiropractic treatment includes many therapeutic options, as outlined in Table 1. Spinal manipulation is typically considered the defining element of chiropractic practice. There is reasonable evidence supporting the safety and effectiveness of spinal manipulation for low back pain, [16] neck pain, [17] and chronic/recurrent headaches. [18] However, at present, there is only minimal evidence on the safety and effectiveness of spinal manipulation along with other alternative therapies for pregnant women. [3, 15] Scarce outcomes data on any chiropractic treatment of low back pain of pregnancy have been presented in the peer-reviewed literature. Two retrospective case series [19, 20] and one case report [21] describe pain reduction in the majority of cases; however, all three reports have methodological limitations. Particularly unclear is the role of spinal manipulation, the chiropractic treatment method presently supported by the most evidence of safety and effectiveness for general low back pain. [22] It has often been written that low back spinal manipulation should be avoided in low back pain of pregnancy cases, [23, 24] but no data have been presented to support this finding.

The purpose of this study, therefore, is to describe the response of a group of consecutive cases of women with low back pain of pregnancy who underwent chiropractic care including spinal manipulation.

METHODS

This study is a retrospective case series (Level IV Evidence) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Bridgeport College of Chiropractic. All cases of pregnant women presenting for chiropractic treatment to the author’s private practice in San Francisco, California, during 12 consecutive months were reviewed. Cases were retrieved by a search of the practice’s electronic database for instances of the ICD code V22.2 (pregnancy, incidental). The charts of these women were then reviewed for the following inclusion criteria: pregnant woman; complaint of low back pain; use of the 11-point Numerical Pain-Rating Scale, a pain measure of established reliability and validity, [25] by every woman at each visit; consistent description of treatments used; clear description of treatment frequency and duration; and clear description of occurrence or lack of adverse effects.

All records were reviewed by the author, and no identifiable subject information was disclosed during any part of this project. Data were extracted from charts that met the above inclusion criteria and were entered into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) for tabulation.

Diagnostic work-up included standard history and physical examination with regional orthopedic and neurological testing. All women were screened for signs and symptoms of serious pathology (fracture, malignancy, infection, cauda equina syndrome) presenting as low back pain.

All women were treated by the same clinician. Active care consisted of reassurance and education, advice on body mechanics, and exercise instruction. Passive treatments were manual myofascial release, manual joint mobilization, and manual spinal manipulation. The most commonly used spinal manipulation maneuvers were procedures aimed at the lumbar facet joints and/or the sacroiliac joints. This involves the subject lying in the lateral decubitus position with the hip and knee flexed, upper extremities folded, and forearms resting on the chest. The chiropractor stands facing the subject at approximately a 45° angle to the table. The chiropractor contacts the given region of the subject’s spine with the hypothenar region of one hand; the other hand contacts the subject’s crossed forearms. At first, relatively low offsetting forces are applied to bring the spinal region to the end range of passive motion. Next, the high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust is delivered. These procedures have been well described elsewhere. [26] For the women in this study, modifications in technique delivery were made to ensure comfort and avoid abdominal compression; and the clinician attempted to use the lowest amount of force necessary. However, the goal of each spinal manipulation procedure was grade V joint motion and articular cavitation or “popping,” and this occurred in most instances.

RESULTS

Table 2 The electronic search yielded 18 cases. On review, one was a case of headache and neck pain without low back pain and, therefore, was excluded. The remaining 17 were cases of low back pain. Of these, 8 complained of local pain at some point between the lowest rib and the gluteal fold; 5 had pain radiating to the posterior thigh; 2 to the inguinal region; and 2 to the posterior calf. In all women, straight leg raise testing was negative, and lower extremity motor strength, deep tendon reflexes, and sensation were intact. These 17 cases met all inclusion criteria and were analyzed. Baseline characteristics of these women are described in Table 2. Of these 17 women, 8 were self-referred, 7 were referred by obstetricians, and 2 by midwives.

The overall group mean Numerical Pain-Rating Scale score decreased from 5.9 (range 2–10) at initial presentation to 1.5 (range 0 –5) at termination of care. When considered individually, one of the 17 (5.8%) women did not demonstrate any clinically important improvement. For the Numerical Pain-Rating Scale, this has been reported to be a decrease of 2 or more points. [27] After eight visits in 21 days, the Numerical Pain-Rating Scale score in this woman changed from 6 to 5.

The remaining 16 of 17 (94.1%) women demonstrated clinically important improvement. The average time to initial clinically important pain relief was 4.5 (range 0–13) days after initial presentation, and the average number of visits undergone up to that point was 1.8 (range 1–5). At termination of care, the average Numerical Pain- Rating Scale score for these 16 women was 1.3 (range 1–4). The average time to termination of care was 24.4 days (range 5–62) after initial presentation, and the average number of total visits undergone was 5.6 (range 3–15). During the course of care, all women were questioned about the occurrence of adverse effects. None of the 17 women reported any adverse effects.

DISCUSSION

Whether low back pain of pregnancy is a unique pathology or is simply the occurrence of mechanical spinal pain during pregnancy remains controversial. [7, 9] Present understanding of the etiology of low back pain in pregnant women is as limited as the understanding of the etiology of low back pain in nonpregnant individuals. However, it is clear that many pregnant women suffer from low back pain, the pain can be severe and disabling in some, and a large proportion of cases go untreated.

There is no gold standard treatment for low back pain of pregnancy. Minimizing pharmacologic interventions is a common goal, but typical nonpharmacologic options are limited. Most physical agents commonly used in physical therapy (therapeutic ultrasound, electrical stimulation, etc.) are contraindicated in pregnancy. [28] A recent systematic review of physical therapy interventions for low back pain of pregnancy identified only three high-quality prospective controlled trials and found no evidence supporting effectiveness. [29]

Chiropractic treatment including spinal manipulation is sometimes used for pregnant women with low back pain. Currently, the mechanism of action of spinal manipulation is poorly understood. However, basic science studies have shown that manipulation results in increased joint range of motion, [30] modulated joint kinematics, [31] regional hypoalgesia, [32] and altered muscle tone. [33] Therefore, patients may benefit from increased joint motion and/or decreased joint or muscle pain. This may be relevant to low back pain of pregnancy, because preliminary evidence suggests that asymmetric stiffness of the sacroiliac joints is related to the presence of low back pain in pregnant women.

This retrospective case series presents outcome data on chiropractic treatment for women with low back pain of pregnancy. Yet, this is low level evidence, and there are limitations inherent in this study design. No conclusions on effectiveness can be drawn from any case series. However, because no adverse effects occurred during the treatment period, this work does provide preliminary evidence that chiropractic treatment was safe for this group of women.

About half of the women in this study were referred by prenatal providers, and half were self-referred. However, comparisons of expectations and outcomes of either group cannot be made because of the small number of subjects. In addition, multiple treatments were used in each case. Although this is typical of chiropractic practice in the field, there was no attempt to characterize the response to any individual treatment component. Furthermore, all treatment was delivered by one provider in one private practice location. Finally, there was no attempt to follow cases beyond the termination of care; therefore, the duration of apparent pain relief is not known.

Further work is needed to better understand the safety and effectiveness of chiropractic treatment for low back pain of pregnancy. A reasonable approach would be a prospective cohort study comparing two groups of women from one prenatal facility, with one group receiving chiropractic treatment and the other receiving standard medical care not involving chiropractic referral or treatment.

CONCLUSION

This study described the results of chiropractic treatment including spinal manipulation for 17 women with low back pain of pregnancy. Sixteen of the 17 cases (95%) demonstrated clinically important improvement in pain intensity throughout the course of treatment. No adverse effects occurred in any of the 17 cases. The results of this study suggest that chiropractic treatment was safe in these cases and support the hypothesis that it may be effective for reducing intensity of low back pain of pregnancy. Substantial prospective work is needed to test this hypothesis.

References:

Ostgaard HC.

Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy.

Spine 1991;16:549 –52.Kristiansson P, Svärdsudd K, von Schoultz B.

Back pain during pregnancy: A prospective study.

Spine 1996;21:702– 8.Wang SM, Dezinno P, Maranets I, Berman MR, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN.

Low back pain during pregnancy: Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes.

Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:65–70.Skaggs C, Nelson M, Prather H, Gross G.

Documentation and classification of musculoskeletal pain in pregnancy.

J Chiro Educ 2004; 18:83–4.Mens JMA, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, et al.

Understanding peripartum pelvic pain: Implications of a patient survey.

Spine 1996;21: 1363–70.Franklin ME, Conner-Kerr T.

An analysis of posture and back pain in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998;28:133– 8.Ostgaard HC.

Influence of some biomechanical factors on low back pain in pregnancy.

Spine 1993;18:61–5.Hirabayashi Y, Shimizu R, Fukuda H, Saitoh K, Furuse M.

Anatomical configuration of the spinal column in the supine position.

II. Comparison of pregnant and non-pregnant women.

Br J Anaesth 1995;75:6–8.Mogren IM, Pohjanen AI.

Low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy: Prevalence and risk factors.

Spine 2005;30:983–91.Damen L, Buyruk HM, Guler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ.

The prognostic value of asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints in pregnancy-related pelvic pain.

Spine 2002;27: 2820–4.Buyruk HM, Stam HJ, Snijders CJ, Lameris JS, Holland WP, Stijnen TH.

Measurement of sacroiliac joint stiffness in peripartum pelvic pain patients with Doppler imaging of vibrations (DIV).

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999;83:159–63.Coulter ID, Hurwitz EL, Adams AH, Genovese BJ, Shekelle PG.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 (Feb 1); 27 (3): 291–298Christensen MG, Kerkhoff D, Kollasch MW.

Job Analysis of Chiropractic 2000

Greeley (CO): National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, 2000.Stapleton DB, MacLennan AH, Kristiansson P.

The prevalence of recalled low back pain during and after pregnancy: A South Australian population survey.

Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;42:482–5.Allaire AD, Moos MK, Wells SR.

Complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy: A survey of North Carolina certified nurse-midwives.

Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:19 –23.van Tulder MW, Furlan AD, Gagnier JJ.

Complementary and alternative therapies for low back pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:639 –54.Gross AR, Hoving JL, Haines TA, Goldsmith CH, Kay T, Aker P, Bronfort G,

Cervical Overview Group.

A Cochrane review of manipulation and mobilization for mechanical neck disorders.

Spine 2004;29:1541– 8.Bronfort G, Nilsson N, Haas M, et al.

Non-invasive Physical Treatments for Chronic/Recurrent Headache

Cochrane Database Syst Review 2004; (3): CD001878Guadagnino MR.

Spinal manipulative therapy for 12 pregnant patients suffering from low back pain.

Chiro Tech 1999;11:108 –11.Diakow PR, Gadsby TA, Gadsby JB, Gleddie JG, Leprich DJ, Scales AM.

Back pain during pregnancy and labor.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991;14:116–8.Potter GE, Cassidy JD.

Diagnosis and manipulative management of post-partum back pain: a case study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1979;2:99 –102.Gatterman MI, Cooperstein R, Lantz C, Perle SM, Schneider MJ.

Rating specific chiropractic technique procedures for common low back conditions.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001;24:449 –56.DiMarco DB.

The female patient: Enhancing and broadening the chiropractic encounter with pregnant and postpartum patients.

J Amer Chir Assoc 2003;40:18 –24.Parsons C.

Back care in pregnancy.

Mod Midwife 1994;4:16–9.Flaherty SA.

Pain measurement tools for clinical practice and research.

AANA J 1996;64:133– 40.Triano JJ, Schulz A.

Loads transmitted during lumbosacral SMT.

Spine 1997;22:1955– 64.Farrar JT, Berlin JA, Strom BL.

Clinically important changes in acute pain outcome measures: A validation study.

J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:406 –11.Borg-Stein J, Dugan SA, Gruber J.

Musculoskeletal aspects of pregnancy.

Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:180 –92.Stuge B, Hilde G, Vollestad N.

Physical therapy for pregnancyrelated low back and pelvic pain: A systematic review.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003;82:983–90.Nilsson N, Christensen HW, Hartvigsen J.

Lasting changes in passive range of motion after spinal manipulation: A randomized, blind, controlled trial.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1996;19:165– 8.Lehman GJ, McGill SM.

Spinal manipulation causes variable spine kinematic and trunk muscle electromyographic responses.

Clin Biomech 2001;16:293–9.Vernon, H.

Qualitative Review of Studies of Manipulation-induced Hypoalgesia

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000 (Feb); 23 (2): 134–138Herzog W, Scheele D, Conway PJ.

Electromyographic responses of back and limb muscles associated with spinal manipulative therapy.

Spine 1999;24:146 –152

Return to PEDIATRICS

Return to FEMALE ISSUES

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to PREGNANCY AND CHIROPRACTIC

Since 1-16-2006

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |