Spinal Pain and Co-occurrence with Stress and

General Well-being Among Young Adolescents:

A Study Within the Danish National Birth CohortThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Journal of Pediatrics 2017 (Jun); 176 (6): 807–814 ~ FULL TEXT

Sandra Elkjær Stallknecht & Katrine Strandberg-Larsen & Lise Hestbæk & Anne-Marie Nybo Andersen

Department of Public Health, Section of Social Medicine,

University of Copenhagen,

Øster Farimagsgade 5, 1014, Copenhagen, Denmark.

stallknecht.se@gmail.com

This study aims to describe the patterns in low back, mid back, and neck pain complaints in young adolescents from the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) and to investigate the co-occurrence of spinal pain and stress and general well-being, respectively. Cross-sectional data from the 11-year follow-up of DNBC were used. As part of a web-based survey, a total of 45,371 young adolescents between 10 and 14 years old completed the Young Spine Questionnaire, the Stress in Children Questionnaire, and a one-item question on general well-being. Associations between spinal pain and, respectively, stress and general well-being were estimated by means of multiple logistic regression models. Almost one fifth of boys and one quarter of girls reported spinal pain. Compared with adolescents who reported no stress, adolescents reporting medium and high values of stress had odds ratios (OR) of 2.19 (95% CI 2.08-2.30) and 4.73 (95% CI 4.28-5.23), respectively, of reporting spinal pain (adjusted for age, gender, and maternal education). Adolescents who reported poor general well-being had an OR of 2.50 (95% CI 2.31-2.72) for reporting spinal pain compared to adolescents with good general well-being.

CONCLUSION: Spinal pain in childhood and adolescence is strongly associated with spinal pain and generalized pain in adulthood. [2, 7, 11]. Therefore, it is of great importance to seek to treat and prevent spinal pain in children both to prevent discomfort for the child but also to reduce the individual and social costs of spinal pain in adulthood. If spinal pain among children and adolescents involves psychosocial well-being, then treatment as well as preventive initiatives might include psychosocial approaches, e.g., psycho education and development of appropriate coping strategies.

There are more articles like this @ our: Pediatrics Section KEYWORDS: Back pain; Lumbar pain; Neck pain; School children; Thoracic pain

What is Known: What is New:

The prevalence of spinal pain increases rapidly during childhood and adolescence, but different measurement instruments result in great variation in the estimates of spinal pain in children and adolescents.

Some studies have shown that different psychosocial measures are associated with spinal pain in children and adolescents.

Spinal pain, as measured by the newly developed and validated Young Spine Questionnaire, is a common complaint in young adolescents aged 10–14 years.

Spinal pain in young adolescents co-occurs with stress and poor general well-being.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

Low back pain is a public health concern as it is the leading cause of years lived with disability, while neck pain ranks fourth [29], and spinal pain has enormous costs to both the individual and society due to disability pensions and treatment costs. [19] Spinal pain often presents early in life and the prevalence increases rapidly during adolescence to reach adult levels at the age of 18 years. [7, 14] A meta-analysis from 2013 found a point prevalence of low back pain of 12% among adolescents aged 9–18 years, whereas the 12-month prevalence was 34%. [3] However, the included studies showed great variation in the estimates of the prevalence. Estimates from the Nordic countries showed a weekly occurrence of spinal pain around 20% [28], and a small Danish study showed a lifetime prevalence of spinal pain of 86% in a population of adolescents aged 11–13 years with neck pain being the most prevalent. [1] However, little is known about pattern of spinal pain among adolescents.

The extent to which the individual is able to cope with the pain is of great prognostic importance. It is believed that the individual’s experience of the pain, in addition to somatic conditions, might depend on coping strategies and psychological and psychosocial conditions. [7, 26] In studies of adult populations, a clear relationship between psychosocial factors and spinal pain has been demonstrated [10, 17, 22], suggesting that psychosocial factors are important predictors of spinal pain. In children and adolescents, there is sparse evidence on the potential co-occurrence of psychosocial well-being and spinal pain. However, some studies have examined how emotional problems, measured with five questions from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), were associated with spinal pain in school children aged 11–14 years. [21, 30] Furthermore, spinal pain has been associated with perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and other social, psychological, and emotional factors in adolescents. [6] In addition, poor general well-being has previously been associated with spinal pain, in the lower back, in school children of different ages. [9, 27] The identified studies generally contain only small study populations and use very diverse measures of spinal pain.

The aim of this study was to describe the patterns in low back, mid back, and neck pain as reported by young adolescents, using the newly developed Young Spine Questionnaire in the 11-year follow-up of the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC), and to investigate the association between spinal pain and stress and general well-being, respectively.

Participants and methods

The Danish National Birth Cohort is a nationwide study of children, enrolled via their mothers, and followed from intrauterine life and onwards. [24] The 11-year follow-up commenced in July 2010, by inviting the part of the cohort older than 11 years to participate, and from then and until October 2014, the children were invited to participate on their 11-year birthday. A total of 87,322 mother-child pairs were invited to complete web-based questionnaires that focused on the child’s lifestyles, social life, well-being, physical activity, diet, and health. In the present study, we used data from the child-completed questionnaire and our study is therefore by design cross-sectional. The young adolescents could sign in and out of the questionnaire, and thus, they were not forced to answer the entire questionnaire at once and, if needed, the questions could be read aloud by the computer.

Spinal pain

The 11-year follow-up questionnaire included a sub-division of the Young Spine Questionnaire (YSQ) [15] that describes life time experience of pain in the low back, mid back, and neck regions separately. The first question was “How often have you had pain in the neck?” and response options were “Often,” “Once in a while,” “Once or twice,” and “Never”. If the young adolescent reported to have experienced neck pain, they were asked to note the intensity of the worst pain ever in the neck using the revised version of the Faces Pain Scale (rFPS) [13], which is a scale based on six faces with expressions illustrating progressively worse pain. The questions were repeated for the mid back and low back regions. An illustration with the three spinal regions clearly shaded and labeled was shown alongside these questions (Figure S1). Finally, questions on limitations in sport participation (“Has neck or back pain sometimes stopped you from doing sports?”), absence from school (“Have you stayed home from school because of neck or back pain?”), and treatment-seeking behavior (“Have you been to a doctor, chiropractor or physiotherapist because of neck or back pain?”) due to spinal pain were included. The response options for these questions were also “Often,” “Once in a while,” “Once or twice,” and “Never”.

For the regression analyses, spinal pain was categorized in a number of binary variables. Low back pain was defined as a report of pain in the lower back “often” or “once in a while” and a score on the rFPS of 3 or above. Pain in the mid back and neck regions was defined similarly. Overall spinal pain was defined if the child fulfilled the definition for either low back pain, mid back pain, or neck pain.

In addition, two variables on limitations and treatmentseeking behavior due to spinal pain were coded. Limitations due to spinal pain were defined as reported limitations in sport participation or reported absence from school “Often”, “Once in a while”, or “Once or twice” and were conditioned on overall spinal pain. Thus, limitations in sport participation and absence from school were combined in one measure for limitations. Treatment-seeking behavior due to spinal pain was coded in a similar manner.

Psychosocial measures

The psychosocial measures we used were stress level and general well-being. Adolescents were asked to complete the Stress in Children (SiC) Questionnaire [25] about physical, psychological, and behavioral responses to stress load, stressors, and perceived stress. The questionnaire contains 21 statements with four possible response options for each statement: “Never”, “Sometimes”, “Often”, and “Very often”. Advised by the author of the questionnaire [25], we constructed a scale by summing the answers and dividing the total score by the number of statements, giving an average score. The eight statements that are encoded reversely were recoded before the statements were added up. The average scale score (SiC score) ranges from 1 to 4. Also, advised by the author of the questionnaire, we used the predefined cutoff points to categorize stress into “No stress” (SiC scores <2), “Medium stress” (SiC score 2 to <2.5), and “High stress” (SiC score ≥2.5).

Additionally, adolescents were asked how they feel about their life at present on a scale of 11 points from “worst” (=0) to “best” (=10) life. This measure is an adapted version of the Cantril Ladder for use in adolescents. [4] We used a cutoff point of 6, which has previously been used elsewhere [5], to dichotomize into the following: “good general well-being” (score of 6 or more) versus “poor general well-being”.

Covariates

The analyses were adjusted for the following covariates: age (10–11, 12, 13–14 years) and gender of the child, and the highest completed or ongoing maternal educational level at child age 7 (primary education, secondary education, tertiary education, or higher) as registered in Statistics Denmark.

Restriction of sample

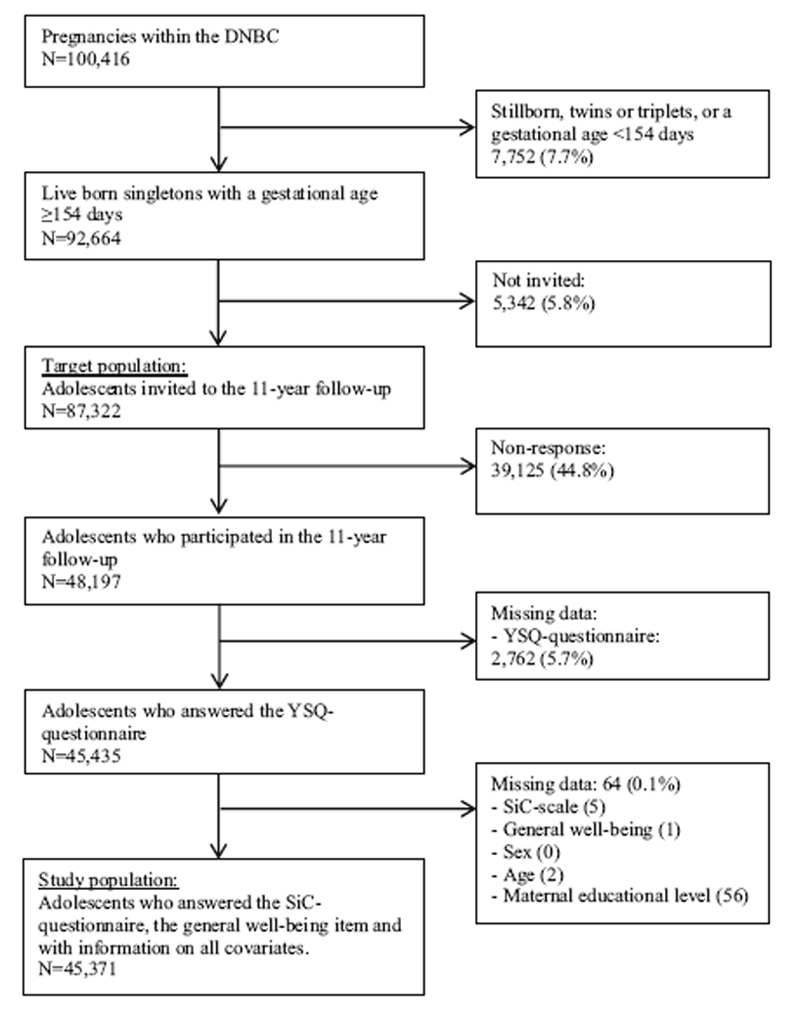

Figure 1 A total of 87,322 children were invited to the 11-year followup questionnaire, of which 39,125 (44.8%) did not respond. The analysis sample was restricted to adolescents who answered all questions regarding spinal pain, stress, well-being, gender, and age and with information on maternal educational level. There were 2,762 (5.73%) who did not answer the YSQ and an additional 64 (0.14%) with missing information on the SiC Questionnaire, the general well-being variable, or any of the covariates. Thus, the study population consisted of 45,371 young adolescents (Figure 1).

Statistical analyses

Chi-square and Student’s t test were used to examine gender differences in the distribution of spinal pain and pain intensity, respectively.

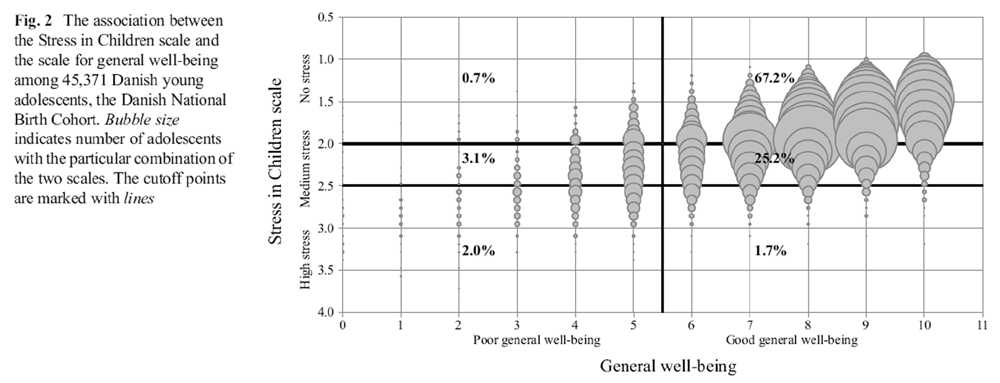

We calculated the Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient between the SiC scale and the scale for general well-being and compared the distribution in a bubble plot to examine the correlation of these two psychosocial measures.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate the crude and adjusted associations, expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95%confidence intervals (95% CI), between the psychosocial measures and various measures for spinal pain. The analyses were not stratified by gender, as testing for effect modification did not show any significant (P < 0.05) interaction with gender and the psychosocial measures in any of the models. The presented estimates are from models where stress and general well-being were included separately, but we also analyzed data by including them simultaneously in the models. All statistical analyses were carried out in SAS version 9.4.

Results

Table 1

Table 2

Figure 2

Table 3

Table 4 Nearly one fifth of boys (17.9%) and one quarter of girls (23.8%) reported spinal pain in one or more regions, and increasing frequency of spinal pain was associated with rising child age and lower maternal educational level (Table 1). The most prevalent pain area for both girls and boys was the neck, followed by the mid back and lastly the low back, and spinal pain was more frequent in girls in all three regions (Table 2). Furthermore, girls reported higher pain intensity than boys in all spinal regions (Table 2). Among young adolescents with spinal pain in one or more regions, one third reported limitations in doing sports (girls, 35.1%; boys, 31.8%), every sixth reported absences from school (girls, 17.8%; boys, 14.5%), and one in four reportedly sought medical care (girls, 26.0%; boys, 24.2%).

The SiC scale correlated moderately with the scale for general well-being with a Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient of 0.56 (P < 0.001). The correlation is illustrated in Figure 2. The figure also illustrates that not all young adolescents classified with poor general well-being were classified with medium or high stress level or vice versa. Using the SiC scale cutoff point of ≥2.5, 3.7% of included young adolescents were classified with high stress level, of which more than half (2.0% points) also had poor general well-being. There was 5.8% of the included young adolescents who were classified with poor general well-being and the majority of these adolescents (5.1% points) had medium or high stress levels. No notable gender differences were observed in the way the SiC scale correlated with the scale for general well-being.

We observed a stepwise association between stress and spinal pain in one or more regions, which was only slightly weakened after adjustment for age, gender, and maternal education. In the adjusted analyses, young adolescents who reported medium and high values of stress had an OR of 2.19 (95% CI 2.08–2.30) and 4.73 (95% CI 4.28–5.23), respectively, of reporting spinal pain compared to young adolescents without stress (Table 3).Young adolescents who reported poor general well-being had an OR of 2.50 (95% CI 2.31–2.72) for reporting spinal pain compared to young adolescents with good general well-being (Table 3). For both the stress level and general well-being, the same pattern was seen for limitations and treatment-seeking behavior due to spinal pain (Table 4) and additionally the same pattern was seen for all three separate spinal pain regions, with the associations being strongest for the neck and mid back (Table S1 and Table S2).

Stratified analyses on gender showed similar associations for spinal pain in relation to stress and general well-being among boys and girls, respectively. Modeling stress and general well-being simultaneously, weakened the associations, and this was most pronounced for general well-being, but both associations remained statistical significant.

Discussion

Spinal pain was frequently reported by Danish young adolescents. Around one fifth of boys and one quarter of girls reported spinal pain in one or more regions, and the most prevalent area where both girls and boys reported pain was the neck. Among young adolescents with spinal pain, one third reported limitations in doing sports, every sixth reported absences from school, and one in four reportedly sought medical care. Both stress and poor general well-being were associated with spinal pain as well as with limitations and treatment-seeking behavior due to spinal pain. The association between stress and spinal pain displayed a stepwise increasing pattern.

A meta-analysis from 2013 found great variability in estimates of how prevalent low back pain is among children and adolescents. [3] The variability may be due to differences in sample selection, age and gender distribution, definition of low back pain, reporting method, and recall period. The occurrence of spinal pain found in the present study is consistent with previously detected weekly incidence of spinal pain among 11–15-year-old Danish children. [28] To our knowledge, there is only one study besides the present using the newly developed instrument YSQ. This study showed a high lifetime prevalence of spinal pain (86%) in Danish adolescents aged 11–13 years, but if limiting the definition to spinal pain BOften” or BOnce in a while,” as in the present study, the prevalences were reduced to 36%, 24%, and 20% for neck pain, mid back pain, and low back pain, respectively. [1] It is likely that adding a criterion for pain intensity to the spinal pain definitions would further reduce the prevalence rates to a level similar to the present study. Also, Aartun et al. found neck pain to be the most common spinal pain site and low back pain the least frequent, which is distinct from adult populations where pain in the lower back followed by the neck are the most common regions with spinal pain. [18] A number of studies showed, similarly to the present study, that girls are more likely to report spinal pain compared to boys. [1, 30]

We could not identify any studies using the same instruments to examine the association between spinal pain and stress or general well-being as the present study. However, the sparse evidence that exists on the relationship between spinal pain and psychosocial factors is consistent with the results of this study. [6, 9, 21, 27, 30]

This study has several strengths. It is one of the first studies using the instrument YSQ to estimate the occurrence of spinal pain in a large population of young adolescents. The YSQ has been shown to be feasible, have content validity, and be well understood in children aged 9 to 11 years. [15] Also, the instruments used to measure stress and general well-being were validated in young adolescents. [16, 25] It was only necessary to exclude a few adolescents from the analyses due to missing values and we had access to background factors for confounder control. We decided to include relatively few potential confounders to prevent over adjustment and avoid including variables that were part of the SiC instrument. Finally, all questions were pilot-tested, and the questions were found to be easily understood among the target population.

However, this study does comprise some limitations. Firstly, this cross-sectional study cannot determine whether spinal pain is caused by stress and poor general well-being or vice versa. The cause-effect relationship between spinal pain and stress and general well-being, respectively, is likely to be mutually dependent. Likewise, it is not possible to conclude anything about the underlying mechanisms and there might be different mechanisms between the two psychosocial measures and the various measures for spinal pain, including spinal regions, and limitations in sport participation, absence from school, and treatment-seeking behavior due to spinal pain.

Secondly, the participants of the 11-year follow-up are a selected sample. Only 30% of eligible pregnant women were enrolled in the DNBC cohort [24] and only 55% of the invited young adolescents responded to the 11-year follow-up. Pregnant woman who participated in the DNBC were generally healthier and had higher socioeconomic status than woman who did not participate [23] and this selection has continued in the follow-ups. [8] The differential drop out pattern could induce non-participation bias, as children of parents with lower socioeconomic status and shorter length of education have higher incidence of spinal pain. [12, 22] Thus, it is anticipated that this study may underestimate the occurrence of spinal pain among Danish young adolescents. Furthermore, it is conceivable that adolescents with spinal pain, high levels of stress, and poor general well-being to a greater extent did not participate in the 11-year follow-up due to lack of energy or interest. If this hypothetical scenario is correct, the effect estimates will potentially be underestimated.

Thirdly, there might be a potential effect of parents’ possible presence when the child answered the questionnaire at home, since one in three of the adolescents sat with one of their parents while completing the questionnaire. However, if the potential influence by parents should have biased our findings, the adolescents’ responses to both the YSQ as well as the SiC and well-being questions should depend upon systematic differences in completion of the questionnaire, which we find unlikely.

This study indicates that spinal pain may involve, or at least co-occur with, psychosocial well-being among young adolescents. It is plausible that in some cases children’s complaints about spinal pain may be an expression of frustration with psychosocial failure to thrive which the child cannot otherwise express. Psychosomatic symptoms are frequent among children and adolescents [20] and can be manifested in different ways, e.g., headache, abdominal pain, and musculoskeletal pain, including spinal pain. On the other hand, the pain itself might also lead to some degree of social or emotional distress, resulting in poor scores on the stress and wellbeing parameters.

Spinal pain in childhood and adolescence is strongly associated with spinal pain and generalized pain in adulthood. [2, 7, 11]. Therefore, it is of great importance to seek to treat and prevent spinal pain in children both to prevent discomfort for the child but also to reduce the individual and social costs of spinal pain in adulthood. If spinal pain among children and adolescents involves psychosocial well-being, then treatment as well as preventive initiatives might include psychosocial approaches, e.g., psycho education and development of appropriate coping strategies.

Acknowledgements

The Danish National Research Foundation established the Danish Epidemiology Science Centre, where the Danish National Birth Cohort was initiated. The cohort is furthermore a result of a major grant from this foundation. Additional support for the DNBC is obtained from the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Augustinus Foundation, and the Health Foundation. The DNBC 11-year follow-up was supported by grants from the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF) and the Lundbeck Foundation.

Authors’ contributions

Sandra Elkjær Stallknecht: Ms. Stallknecht analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Katrine Strandberg-Larsen: Ms. Strandberg-Larsen made substantial contributions to conception and design as well as analysis and interpretation of data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Lise Hestbæk: Ms. Hestbæk developed the Young Spine Questionnaire, made substantial contributions to interpretation of results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Anne-Marie Nybo Andersen: Ms. Andersen made substantial contributions to interpretation of results and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors conceptualized and designed this study. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This particular work was supported by the University of Copenhagen, the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF), and the Lundbeck Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

DNBC = Danish National Birth Cohort

OR = Odds ratio

rFPS = The revised version of the Faces Pain Scale

SD = Standard deviation

SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

SiC = Stress in Children

References:

Aartun E, Hartvigsen J, Wedderkopp N, Hestbaek L (2014)

Spinal Pain in Adolescents: Prevalence, Incidence, and Course:

A School-based Two-year Prospective Cohort Study in 1,300 Danes Aged 11-13

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014 (May 29); 15: 187Brattberg G (2004)

Do pain problems in young school children persist into early adulthood?

A 13-year follow-up.

Eur J Pain 8(3):187–199Calvo-Munoz I, Gomez-Conesa A, Sanchez-Meca J (2013)

Prevalence of Low Back Pain in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis

BMC Pediatr. 2013 (Jan 26); 13: 14Cantril H (1965)

The pattern of human concerns.

Rutgers University Press, New BrunswickCurrie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, Currie D, de Looze M, Roberts C, Samdal O, Smith O, Barnekow V (2012)

Social Determinants of Health and Well-being Among Young People

Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study:

international report from the 2009/2010 survey.

WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 6),

CopenhagenDiepenmaat AC, van der Wal MF, de Vet HC, Hirasing RA (2006)

Neck/shoulder, low back, and arm pain in relation to computer use, physical activity,

stress, and depression among Dutch adolescents.

Pediatrics 117(2):412–416Dunn KM, Hestbaek L, Cassidy JD.

Low Back Pain Across the Life Course

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013 (Oct); 27 (5): 591-600Greene N, Greenland S, Olsen J, Nohr EA (2011)

Estimating bias from loss to follow-up in the Danish National Birth Cohort.

Epidemiology 22 (6): 815–822Gunzburg R, Balague F, Nordin M, Szpalski M, Duyck D, Bull D, Melot C (1999)

Low back pain in a population of school children.

Eur Spine J 8(6):439–443Hemingway H, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld S, Marmot M (1997)

Sickness absence from back pain, psychosocial work characteristics and employment grade

among office workers.

Scand J Work Environ Health 23(2):121–129Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche C (2006)

The Course of Low Back Pain from Adolescence to Adulthood: Eight-year Follow-up of 9600 Twins

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006 (Feb 15); 31 (4): 468–472L, Korsholm L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO (2008)

Does socioeconomic status in adolescence predict low back pain in adulthood?

A repeated cross-sectional study of 4,771 Danish adolescents.

Eur Spine J 17(12):1727–1734Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B (2001)

The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement.

Pain 93(2):173–183Jeffries LJ, Milanese SF, Grimmer-Somers KA (2007)

Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain: A Systematic Overview of the Research Literature

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 (Nov 1); 32 (23): 2630–2637Lauridsen HH, Hestbaek L.

Development of the Young Spine Questionnaire

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013 (Jun 12); 14: 185Levin K, Currie C (2013)

Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the Cantril Ladder for use with adolescent samples.

Soc Indic ResLinton SJ (2000)

A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain.

Spine 25(9):1148–1156Manchikanti L, Singh V, Datta S, Cohen SP, Hirsch JA (2009)

Comprehensive review of epidemiology, scope, and impact of spinal pain.

Pain Phys 12(4):E35–E70Martin, BI, Deyo, RA, Mirza, SK et al.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656–664Mohapatra S, Deo S, Satapathy A, Rath N (2014)

Somatoform disorders in children and adolescents.

German J Psychiatr 17(1): 19–24Murphy B, Buckle P, Stubbs D (2007)

A cross-sectional study of self-reported back and neck pain among English schoolchildren

and associated physical and psychological risk factors.

Appl Ergon 38: 797–804Mustard CA, Kalcevich C, Frank JW, Boyle M (2005)

Childhood and early adult predictors of risk of incident back pain:

Ontario Child Health Study 2001 follow-up.

Am J Epidemiol 162(8):779–786Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J (2006)

Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias?

Epidemiology 17(4): 413–418Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF et al (2001)

The Danish National Birth Cohort—its background, structure and aim.

Scand J Public Health 29(4):300–307Osika W, Friberg P, Wahrborg P (2007)

A new short self-rating questionnaire to assess stress in children.

Int J Behav Med 14(2): 108–117Pincus T, McCracken LM (2013)

Psychological factors and treatment opportunities in low back pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 27(5):625–635Szpalski M, Gunzburg R, Balague F, Nordin M, Melot C (2002)

A 2-year prospective longitudinal study on low back pain in primary school children.

Europ Spine J 11(5):459–464Torsheim T, Eriksson L, Schnohr CW, Hansen F, Bjarnason T, Valimaa R (2010)

Screen-based activities and physical complaints among adolescents from the Nordic countries.

BMC Public Health 10:324Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al.:

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010:

A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet. 2012 (Dec 15); 380 (9859): 2163–2196Watson K, Papageorgiou A, Jones G, Taylor S, Symmons D, Silman A, Macfarlane G (2003)

Low back pain in schoolchildren: the role of mechanical and psychosocial factors.

Arch Dis Child 88(1):12–17

Return to NECK AND BACK PAIN

Since 12-25-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |