A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the Role of

Fear-avoidance Beliefs in Chronic Low Back Pain and DisabilityThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain. 1993 (Feb); 52 (2): 157–168 ~ FULL TEXT

Gordon Waddell, Mary Newton, Iain Henderson, Douglas Somerville and Chris J. Main

Orthopaedic Department,

Western Infirmary,

Glasgow, Scotland UK.

Pilot studies and a literature review suggested that fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity and work might form specific cognitions intervening between low back pain and disability. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) was developed, based on theories of fear and avoidance behaviour and focussed specifically on patients' beliefs about how physical activity and work affected their low back pain. Test-retest reproducibility in 26 patients was high. Principal-components analysis of the questionnaire in 210 patients identified 2 factors: fear-avoidance beliefs about work and fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity with internal consistency (alpha) of 0.88 and 0.77 and accounting for 43.7% and 16.5% of the total variance, respectively.

Regression analysis in 184 patients showed that fear-avoidance beliefs about work accounted for 23% of the variance of disability in activities of daily living and 26% of the variance of work loss, even after allowing for severity of pain; fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity explained an additional 9% of the variance of disability. These results confirm the importance of fear-avoidance beliefs and demonstrate that specific fear-avoidance beliefs about work are strongly related to work loss due to low back pain. These findings are incorporated into a biopsychosocial model of the cognitive, affective and behavioural influences in low back pain and disability. It is recommended that fear-avoidance beliefs should be considered in the medical management of low back pain and disability.

Key words: Low back pain; Disability; Cognitive factors; Fear-avoidance beliefs; Psychometric properties; Cognitive-behavioural analysis; Biopsychosocial model; Medical management; Rehabilitationn

. The 15 items in PAIRS cover a broad range of functional limitations which the patient attributes to pain but only I item includes work.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain and disability are frequently treated by patients and clinicians as if they were synonymous but should be distinguished both conceptually and clinically. Pain is the most common presenting symptom in medical practice [Engel 1959; Penfield 1969]. It is now widely recognised that pain has both sensory and affective dimensions; the current neurophysiological view is that pain activates affective change directly through the reticular system and that this affective disturbance is an integral part of pain rather than a secondary effect [Panksepp et al. ‘1991]. This is reflected in the IASP definition of pain which includes its emotional and aversive qualities [Merskey 1979]. A more comprehensive concept of pain, derived from the gate-control theory of pain [Melzack and Wall 1965; Melzack and Casey 1968] and tested empirically by the McGill Pain Questionnaire [Melzack 1975; Turk et al. 1985; Lowe et al. 1991], includes sensory, affective and cognitive dimensions. From a different background, clinical psychology has further developed and focussed the cognitive- behavioural dimensions of chronic pain [Fordyce 1976; Turk et al. 1983; Turner and Roman0 1990]. In lay usage and clinical practice, however, pain is still regarded primarily as a sensory symptom. Patients and physicians generally think about pain, communicate about pain and treat pain in terms of tissue damage, injury and nociception, although in chronic low back pain there may no longer be any demonstrable structural impairment [Waddell et al. 1992]. Finally, since pain is subjective, clinical assessment of pain is dependent on the patient’s communication of pain whether by verbal report [Melzack 197.5, 1987] or overt pain behaviour [Keefe and Block 1982; Waddell and Richardson 1991].

Disability is restricted function and can be assessed reliably by clinical interview [Waddell and Main 1984], questionnaire [Fairbank et al. 1980; Roland and Morris 1983] or work loss. Disability is always defined as restriction resulting from an impairment [Waddell and Main 1984]. The World Health Organisation [1980] definition of impairment in general is “any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological or anatomical structure or function”. Physical impairment is “pathological, anatomical or physiological abnormality of structure or function leading to loss of normal bodily ability” [Waddell et al. 1992]. In practice the emphasis in clinical evaluation of physical impairment is again on tissue damage. In chronic low back pain, however, functional restriction due to pain, which may be regarded as physiological impairment, may be more important than any anatomical or structural impairment [Waddell et al. 1992]. In chronic pain the major problem lies in the interpretation of ‘psychological impairment’. Psychiatric illness meeting DSM-III criteria would constitute such an impairment [Mendelsson 1988]. More commonly, however, the affective dimension of chronic pain presents clinically as psychological distress in the form of anxiety, increased somatic awareness and depressive symptoms [Waddell et al. 1984; Main et al. 1992a]. This level of distress is not normally diagnostic of psychiatric illness. The extent to which distress can be said to constitute a psychological impairment, in the sense of the definition, then becomes a matter of debate.

In the absence of proportionate physical, physiological or psychological impairment, disability due to chronic low back pain requires further exploration of the patient’s cognitions and pain behaviour.

Pilot studies on the relationship between low back pain and disability

A historical review [Allan and Waddell 1989] suggested that low back pain has affected man throughout recorded history but that chronic disability due to simple backache is a relatively recent and peculiarly Western epidemic [Waddell 1987b]. The increase in low back disability appears to depend more on society’s and medicine’s understanding and management of low back pain than on any change in the biological disorder.

Re-analysis of data from a previous series [Waddell et al. 1992] showed that self-reported disability in activities of daily living was indeed related to severity of pain on a visual analogue scale and also to objective clinical evaluation of current physical impairment (Fig. 11, but the relationship was weak. Severity of pain only accounted for some 10% of the variance of physical impairment and disability. These results have been confirmed by Linton [1985], Waddell [1987a], Riley et al. [1988] and Slater et al. [1991]. Low back disability must therefore also depend on other factors than solely the severity of pain or objective physical impairment.

Regression analysis of a second series [Main and Waddell 1991] showed that a larger proportion of the variance of disability in activities of daily living could be explained by a combination of severity of pain, psychological distress (particularly depressive symptoms) and illness behaviour (Table Ia). The relative importance of pain, depressive symptoms and illness behaviour varied in different patient groups [Waddell et al. 1984] but similar results have also been reported by Reesor [1986] and Reesor and Craig [1988]. This confirms that low back disability also depends on the affective component of pain and on the pattern of illness behaviour which develops - both of which may become just as disabling as pain itself. Work loss due to low back pain is harder to explain and in this series severity of pain, depressive symptoms and illness behaviour explained a smaller proportion of the variance of work loss (Table Ib).

In a third unpublished study loss of time from work depended more on social and work-related factors such as the physical demands of work. In a separate prospective study [Waddell et al. 1986] return to work after spinal surgery was again influenced most by occupational factors. This is supported by other reports that socio-economic and work-related factors may be better determinants of low back disability than either biological or medical factors [Bigos et al. 1991; Volinn et al. 1991].

Jensen et al. [1991] have recently reviewed the relationships among and distinctions between beliefs, coping and adjustment to chronic pain. In our second series quoted above [Main and Waddell 1991] cognitive measures [Wallston et al. 1978; Rosensteil and Keefe 1983; Flor and Turk 1988; Main et al. 1992b] and particularly catastrophising [Rosensteil and Keefe 1983] explained 35% of the variance of the depressive symptoms associated with chronic low back pain, even after allowing for severity of pain. This is consistent with other observations that illness behaviour may depend just as much on cognitive factors as on severity of pain or any physical impairment [Mechanic et al. 1982; Turk et al. 1983; Smith et al. 1986; Philips 1987; Waddell et al. 1989]. It also supports the hypothesis that coping strategies may be an important mediator between pain and depression [Rudy et al. 1988] and hence also low back disability. In this second series [Main and Waddell 1991], however, these measures of coping strategies only accounted for 9% of the variance of work loss after allowing for severity of pain.

A fourth exploratory study of 120 patients found that 3 self-reports about low back pain were significantly related to work loss: pain aggravated by physical activity in general, by walking and by physiotherapy. Similar observations were made by Troup [1988].

From these pilot studies it was postulated that current cognitive measures are too general to explain adequately low back disability [Main and Waddell 1991]. The present study therefore attempted to explore further the clinical, experimental and theoretical nature of cognitions about pain.

Fear-avoidance beliefs

Pain is one of the most powerful aversive drives in animals and humans and is closely allied to fear. The present neurophysiological view is that the systems of fear and pain may interact in the reticular system [Panksepp et al. 1991]. Fear theory is now based on a powerful body of animal experimental work [Denny 1991]. For more than 40 years this has emphasised classical conditioning and the learned nature of fear and avoidance behaviour, though it is important to recognise also the innate, unconditioned nature not only of pain but also of fear and avoidance behaviour [Panksepp et al. 1991]. Fordyce [Fordyce et al. 1968; Fordyce 1976] applied learning theory to behavioural medicine, relating pain behaviour to operant conditioning. The initial emphasis was on positive re-inforcement of pain behaviour. Subsequently, however, he considered ‘avoidance-learning’, i.e., reduction of pain by avoidance behaviour resulting in negative re-inforcement [Fordyce et al. 1982]. He noted that avoidance behaviour was based on anticipated, consequences, so little re-inforcement was required to maintain the behaviour. Philips [1987] further explored the clinical role of avoidance behaviour. She found little evidence that avoidance behaviour reduces chronic pain either on a short- or long-term basis. From a limited mechanical view of pain, avoidance behaviour may at first appear to be adaptive but a broader cognitive-behavioural view shows that in chronic pain it is generally maladaptive. Philips [1987] also emphasised the importance of beliefs and cognitions in avoidance behaviour, unlike the predominantly behavioural emphasis of Fordyce [1976]. Lethem et al. [1983] and Troup et al. [1987] outlined the most specific “fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception” in chronic low back pain. This emphasised the central role of fear of pain and consequent pain-avoidance behaviour as the most important cognitive-behavioural dimension. Troup [1988] later noted that fear avoidance might be of specific relevance to incapacity for work.

It might be argued that fear-avoidance beliefs simply reflect the mechanical characteristics of low back pain and its relationship to physical activity, and this may indeed be the origin of such beliefs. However, other evidence suggests that patients’ perception of physical activity and its relation to pain and also their perception of their physical capabilities are often quite erroneous. Patients with low back pain do generally show lower physical performance levels than normal asymptomatic subjects but their perception of theit physical capacity is reduced more than actual performance [Fordyce et al. 1981; Linton 1985; Schmidt 1985]. Dolce et al. [1986~] showed that pain tolerance, exercise performance [Dolce et al. 1986b] and treatment outcome [Dolce et al. 1986a] all correlate with self-efficacy expectancies, i.e., with patients’ own prediction of their ability to cope. This shows that patients can estimate to some extent their physical performance and it is suggested that this is based on their previous experience [Dolce 1987]. But this does not address the cognitive factors underlying that estimate. Council et al. [1988] found that chronic low back pain patients’ expectations of the pain associated with certain physical activities correlated 0.40-0.74 with their subsequent performance. They concluded that actual performance was best predicted by self-efficacy ratings, which in turn appeared to be determined by pain response expectancies. However, Rachman and Lopatka [1988] showed that 25% of patients with chronic arthritic pain tend to over-predict the amount of pain which they subsequently report on physical exercise. Schmidt [1985] found that the treadmill endurance of chronic low back pain patients was 73% of that of healthy matched controls when they had low external information and feedback.

However, with this particular form of exercise patients did not report any increase in pain. Although post-exercise ratings of exertion were similar in the 2 groups, the low back pain patients actually showed lower levels of physiological demand and stopped because of over-estimate of exertion rather than increased pain. Pope et al. [1980] showed that restricted spinal mobility, reduced flexion-extension torque ratio and reduced straight leg raising due to low back pain were all associated with lower pain threshold and tolerance. Exercise to the limit of pain tolerance is also strongly influenced by conscious feedback of how much exercise has been done [Cairns and Pasino 1977; Fordyce 1988]. In the absence of such feedback, chronic pain patients increase their performance on an incremented exercise programme at the same rate as normal pain-free subjects [Fordyce et al. 1982]. Exercise quotas produce systematic increases in both exercise levels and expectancies of exercise capabilities while reducing worry and concern about exercising [Dolce et al. 1986b]. Finally, patients with low back pain perceive their work as being physically more demanding than do their healthy co-workers [Magora 1973; Dehlin and Berg 1977; Troup et al. 1987]. From this evidence it is clear that while fear-avoidance beliefs may originate from the patient’s own experience of how physical activity affects their pain, fear-avoidance beliefs can then be modified greatly by cognitive and affective factors.

Turk and Flor [1984] pointed to the lack of empirical evidence for cognitive-behavioural theories of chronic low back pain. Caldwell and Chase [1977] made one of the earliest clinical observations of the importance of “over-learning of pain-fear” in chronic low back pain but no data was presented. Slade et al. [1983] related low back disability in students to previous general coping strategies for other types of pain but they did not look specifically at cognitions related to current low back pain. Smith et al. [1986] showed that cognitive errors, particularly over-generalisation about chronic low back pain-related activities, were related to low back disability though this study was limited by the nature of the Cognitive Errors Questionnaire [Lefebvre 1981]. Sandstrom and Esbjornsson [1986] showed that the low back pain patient himself or herself gave the best prediction of return to work after a vocational rehabilitation programme. Two specific questions were used. “I am afraid to start working again, because I don’t think I will be able to manage.” “My closest relatives worry that my condition will deteriorate if I start working.” They concluded that the patient’s attitude towards work should be carefully evaluated before a rehabilitation programme but they did not develop the measurement of beliefs further.

The Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale (PAIRS) Beliefs Questionnaire developed by Riley et al. [1988] specifically attempted to measure patients’ beliefs about the relationship between pain and functional impairment. They developed the instrument in 56 chronic pain patients referred to a multi-disciplinary pain treatment programme. Slater et al. [1991] confirmed its psychometric properties in a small series of 31 male patients attending a general orthopaedic clinic with chronic low back pain. Even in such small series, both studies showed a strong relationship between PAIRS beliefs and functional restriction, even after allowing for severity of pain [Riley et al. 1988] or affective disturbance Water et al. 1991]

The Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA) was designed by Jensen et al. [1987] to assess attitudes considered important in the long term adjustment of chronic pain patients. The original instrument was constructed with 5 a priori scales directed to beliefs about medical cure, pain control, solicitude, disability and medication. They subsequently added a 6th emotional scale [Jensen and Karoiy 1987] and the factor structure of this version was essentially rephcated by Strong et al. [1992]. A 7th harm scale has since been added to assess the extent to which patients believe that pain means they are damaging themselves and that they should avoid exercise [Jensen 1991]. Conceptually, this is very similar to the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) but it does not consider work. There is no pubIished data on the psychometric properties or chnical validity of the SOPA harm scale.

This theoretical analysis, literature review and pilot studies all support the hypothesis that fear-avoidance beliefs may be a specific and powerful cognitive factor in low back pain. The aims of the present study were a-fold. Firstly, to develop a questionnaire to measure fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity and work suitable for routine clinica use in patients with Iow back pain. Secondly, to use that questionnaire to investigate the relationship between low back pain, fearavoidance beliefs and chronic disability in activities of daily living and work loss.

Material and methods

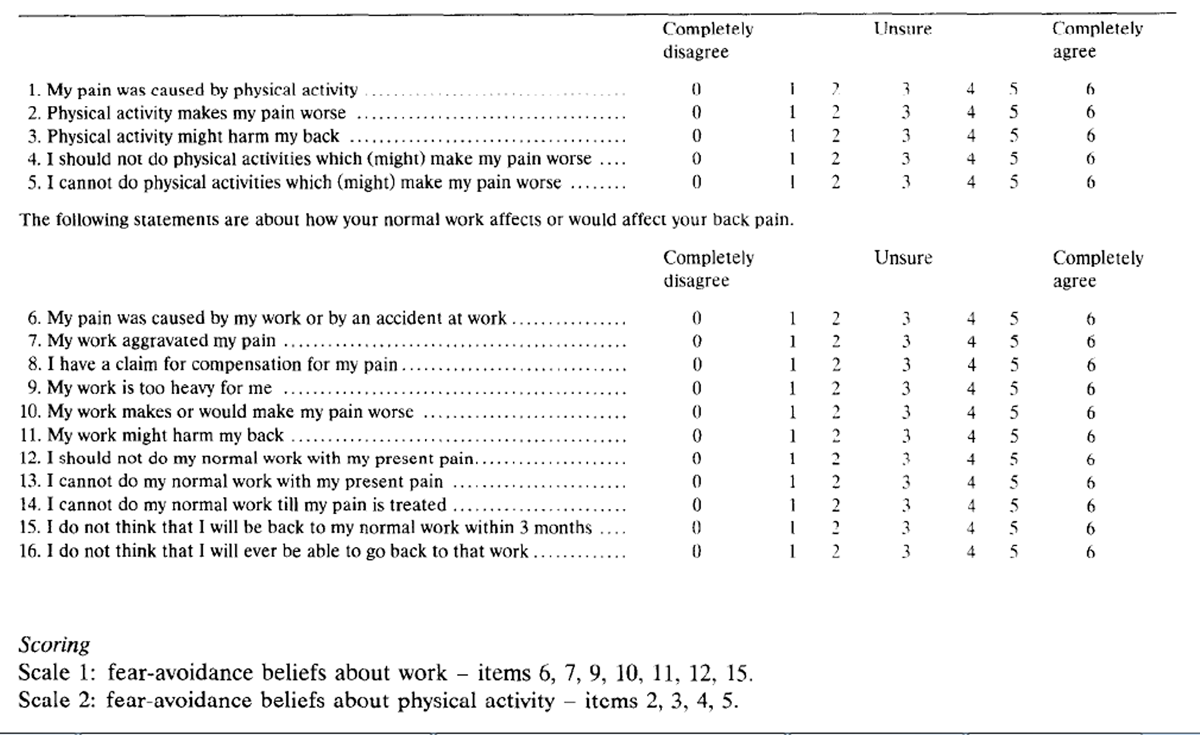

The present FABQ was developed in 2 pilot groups totalling 30 patients attending an orthopaedic out-patient clinic. The FABQ focussed on patients’ beliefs about how physical activity and work affected their current low back pain. It was based mainly on fear theory and fear-avoidance cognitions but also drew on the concept of Disease Conviction [Pilowsky and Spence 1975, 1983] which includes beliefs about the seriousness of the illness and its effect on the patient’s life and on the concepts of somatic focussing and increased somatic awareness [Main 1983]. The final format was a self-report questionnaire of 16 items presented on a single page (Appendix). The items were original though the wording of many of the items was derived from Fordyce’s teaching aphorisms about pain behaviour [Fordyce 1988] and the 2 questions from Sandstrom and Esbjornsson [1986]. Only I item was similar to 1 of the items in PAIRS [Riley et al. 1988] and 3 items to the SOPA harm scale [Jensen 1991]. Each item was answered on a ‘?-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Test-retest stability

Short-term test-retest reproducibility was estimated on 26 out-patients referred to a hospital physiotherapy department with low back pain. The questionnaire was administered on the first attendance for assessment and repeated on the first treatment visit 48 h later. No active treatment was given between these 2 tests. The time interval was chosen to minimise clinical or cognitive change, but also makes it unlikely that patients would remember their previous answers.

Main study

The main study was of 184 patients with low back pain and/or sciatica referred to various hospital out-patients departments: 22% were direct GP referrals to a physiotherapy department, 43% were primary GP referrals to 2 orthopaedic departments in a teaching hospital and a district general hospital. 28% were secondary referrals from other consultants to a regional problem back clinic and 6r% were attending a rehabilitation unit. All patients were Caucasian with English as their native language, 55.7% were male, 44.3% female. All patients were aged 18-60 years, mean age 39.7* 11.7 years. Patients with serious spinal pathology such as tumour, infection or inflammatory disease, spinal fractures, structural spinal deformity, major neurology, history of primary psychiatric disease or alcohol abuse, or inability to read and write were excluded.

The mean time from the first ever attack of low back symptoms was 7.4 ± 8.4 years and mean duration of the present attack 13.7 ± 19.8 months. Work status was 34% still working, 24% off work because of back pain but still had a job, 15% had lost their job because of back pain and 27% not relevant. The mean duration of time off work due to back pain at the time of assessment was 4.0 ± 4.3 months and total work loss over the past year was 6.0 ± 10.8 months.

In the main study clinical assessment of all patients was carried out by one of the authors. A standard medical history and subsequent review of the hospital records checked for any of the exclusion conditions listed above. Clinical assessment of pain included the anatomical pattern, time pattern and severity. The anatomi~ai pattern was low back pain alone in 32%, low back pain plus referred thigh pain in 36% and nerve root pain in 32% [Waddell l982]. The time pattern was acute in 5%, recurrent in 20% and chronic in 75’% [Waddell 1982]. Severity was assessed by a visual analogue pain scale [Waddell 1987a]. The self-report battery included the FABQ, disability in activities of daily living [Roland and Morris 1983] and 2 measures of current psychological distress - the Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire [Main 1983] and modified Zung Depressive Inventory [Zung 1965; Main et al. 1992a].

Data analysis

Reliability statistics were calculated on the 26 patients of the test-retest study. Simple percent agreement on retest was checked by K statistics to allow for the level of chance agreement and distribution effects [Cohen 1960; Fleiss et al. 1969].

The scale structure of the questionnaire was analysed on the combined total of 210 patients from the main study and the reproducibility study and confirmed in 2 random halves. The factor structure was explored using principal-components analysis with varimax rotation [Gorsuch 1974]. An orthogonal rotation was used as this was an exploratory analysis. This maximises the association of each item with its ‘best’ factor to produce the most parsimonious and conceptually clearest scale structure. A series of alternative factor structures was explored and the final structure chosen on the basis of scree, mineigen, correlation matrix and item analysis. Items were accepted on the final factors if they had a loading of at least 0.45 on that factor and less than 0.30 on any other factor. The possibility of higher order factors was checked by non-orthogonal rotation.

The relationship of fear-avoidance beliefs to other clinical variables was analysed in the main study of I84 patients. Significant relationships were identified by correlation statistics and the relationship between disability and fear-avoidance beliefs was then explored further with hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis. The fiied order of entry in the regression analysis was based on theory. Biomedical measures of pain were entered first, accepting that low back pain itself is the primary problem and should be controlled for. Fear-avoidance beliefs were inserted second and depressive symptoms third, on the basis that cognitions develop secondarily to pain and then mediate between pain and depressive symptoms [Rudy et al. 1988].

Results

Test-retest stability

All 16 individual items reached acceptable levels of test-retest reproducibility. 71% of individual answers were identical on retest which is high for 7-point scales. K statistics confirmed that all 16 items had high level of reproducibility. Two items had moderate concordance of 0.41-0.60, 8 had substantial concordance of 0.61- 0.80 and 6 had close to complete concordance of greater than 0.80 [Landis and Koch 1977]. The average level of K for all 16 items was 0.74 and all reached the 0.001 level of significance. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients for the 2 scales (see below) were 0.95 and 0.88.

Distribution of individual items

In the complete series of 210 patients none had to be excluded because of lack of understanding or compliance on the FABQ itself, although 21 patients were unable to complete items 6-16 because they were not employed. Otherwise, there were only 1.3% missing answers and no individual item had greater than 2.1% missing answers. The answers to all 16 individual items were distributed across at least 4 categories and no item had to be excluded from further analysis because of excessively skewed distribution [Maxwell 1971].

Scale structure

Principal-components analysis indicated a 2-factor structure (Table II, Appendix). Consideration of the item content suggested that Factor 1 (FABQl) concerns fear-avoidance beliefs about the relationship between low back pain and work while Factor 2 (FABQ2) concerns fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity in general. Item analysis showed that items 13, 14 and 16 were redundant while item 1 was characterised by low communality and inconsistent factor loadings. Item 8 did not fit on either factor. Non-orthogonal analysis produced an identical factor structure.

An alternative 3-factor solution was unstable with the third factor just reaching mineigen criteria, largely associated with item 8 (compensation) and accounting for a small percentage of the total variance. Alternatively, a single general factor of 11 items yielded an (Y of 0.82 and certainly the 2 factors do inter-correlate 0.39. However, scree, mineigen and the correlation matrix all suggested that a 2-factor structure is stable and statistically reliable. Moreover, treating the 11 items as 1 scale would lose the conceptual differentiation between the 2 dimensions of fear-avoidance beliefs about work and physical activity.

Relationship of FABQ to clinical cariables

FABQl was weakly related to sex (female 19.3 ± 12.7, male 24.0 ± 12.8, t value 2.39, P = 0.02). FABQ2 was not significantly related to sex. Neither factor correlated significantly with age.

The 2 factors were largely independent of any of the biomedical measures of pain (Table III). Only FABQl was related to the anatomical pattern of pain though not in the order of pathological severity. The mean score of FABQl in patients with low back pain alone was 21.9 ±_ 14.3, in low back pain plus referred thigh pain 25.2 ± 12.1 and in nerve root pain 17.8 + 12.0 (analysis of variance: F ratio 4.61, P = 0.01). Only FABQl was significantly related to severity of pain (Table III) but even then the correlation was low with only 5% of variance in common. Neither of the factors showed any significant correlation with total duration, duration of the present episode or time pattern of pain.

Fear-avoidance beliefs correlated strongly with both self-reported disability in activities of daily living and work loss (Table III>. Regression analysis confirmed this relationship (Table IV). Both disability and work loss were poorly explained by any of the biomedical characteristics of pain. Fourteen per cent of the variance of disability was explained by severity of pain but only 5% of work loss in the past year was explained by the time pattern of pain, which is to some extent a statistical artefact. Fear-avoidance beliefs explained a much higher proportion of the variance. Fear-avoidance beliefs about work (FABQl) was consistently the stronger of the 2 scales and explained a highly significant portion of the variance of disability and work loss even after allowance for pain. Fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity explained an additional portion of disability but not of work loss. Analysis of present work loss gave similar results to those presented for total work loss in the past year, although with a generally lower amount of variance explained. Fear-avoidance beliefs about work were consistently more powerful in males than in females accounting for 27% and 35% of the variance of disability and work loss in the past year, respectively, in males but only 17% and 18% in females. When a gender X beliefs interaction was tested, however, it did not enter significantly into the regression equation.

When the rejected items were reconsidered on an individual basis, neither causal beliefs nor compensation added anything to the analysis of either disability in activities of daily living or work loss, though in this series only 18% of patients had or were considering a claim for compensation. Finally, depressive symptoms still explained a small but significant additional proportion of the variance of disability in activities of daily living in males but added little to the analysis of work loss after allowing for fear-avoidance beliefs. This is consistent with findings that depression associated with pain is very largely mediated by and secondary to cognitive factors [Rudy et al. 1988].

Discussion

There are 2 main findings in this study. The first is that there was little direct relationship between pain and disability. This study employed a correlational design and causation could only be confirmed by longitudinal experiment or a true experimental design. Nevertheless, in this analysis severity of pain only explained 14% of the variance of disability in activities of daily living. All of the available biomedical measures combined could only explain 5% of the variance of work loss. Although this may at first seem surprising to many clinicians, it is consistent with the findings of Pilot Studies 1–4.

The second main finding is the strength of the relationship between fear-avoidance beliefs about work and both work loss and disability in activities of daily living. Fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity were weaker but did explain an additional proportion of the variance of disability in activities of daily living.

Compensation also appeared to be less important in this analysis. Disability is generally more protracted in patients with work-related low back injuries though many studies have failed to show any difference in the amount of psychological distress of patients with work-related or non-work-related low back injuries [Mendelsson 1991]. However, fear-avoidance beliefs about work are likely to be profoundly affected by a work-related injury and may more directly and powerfully influence work loss than any secondary gain from compensation.

In this study fear-avoidance beliefs were able to predict a substantial portion of the variance of disability, both in work loss and activities of daily living, both stronger than biomedical measures of pain and over and above these biomedical measures. Specific fearavoidance beliefs about work were stronger than more general fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity. Fear-avoidance beliefs about work appeared to be better able to predict work loss in this study than more general cognitive measures such as the CSQ or PLC in Pilot Study 5. There are certain similarities in the theoretical bases and some of the physical activity items of the FABQ and both PAIRS [Riley et al. 1988] and SOPA [Jensen et al. 1987]. However, the FABQ specifically focuses on work which the present results suggest is most important whereas neither PAIRS nor SOPA assess beliefs about work. To confirm that fearavoidance beliefs about work are the most specific and strongest cognitive factor associated with low back pain further research should compare the FABQ directly with PAIRS [Riley et al. 1988] and the latest version of SOPA including the harm scale [Jensen 1991] and also with more general cognitive measures such as the CSQ and PLC [Main and Waddell 1991].

These findings also confirm the conclusion of the literature review that fear-avoidance beliefs are not simply a reflection of the mechanical characteristics of the low back pain. There was little direct relationship between fear-avoidance beliefs and any of the biomedical characteristics of pain measured in this study (Table III). They were not related to any clinically significant extent to the severity of pain. Indeed, when considering the different anatomical patterns of pain, fear-avoidance beliefs did not increase with pathological severity but rather with increasing uncertainty of diagnosis. In the regression analysis of disability (Table IV) fear-avoidance beliefs added a completely separate and additional dimension to the biomedical characteristics of pain. In their final expression it is the patient’s beliefs rather than the underlying physical reality which govern behaviour. Fear of pain and what we do about pain may be more disabling than pain itself.

There are several limitations to the present study. The analysis was based entirely on self-report measures and should ideally, as far as possible, be checked or compared with externally validated measures. These findings could be tested with alternative and more comprehensive measures of pain such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire [Melzack 1975, 1987] and with behavioural observations [Waddell and Richardson 1991]. It only considered chronic pain and further study is required of acute pain. The dominance of work beliefs means that the FABQ is at present only validated for patients who are or have recently been employed. It provides a more limited single scale (FABQ2) in those who are unemployed or off work for other health or non-health reasons in addition to low back pain. It is unclear how long a person has to be unemployed before they cannot use items 6-16 or whether they tend to answer with reference to their previous work, which is likely to be biased, or to work which they hope to do in the future, which would bc purely hypothetical.

It is possible that the FABQ could be used for housewives with modified instructions to regard household duties as their work, although in this study a number of housewives spontaneously completed the questionnaire on this basis. At present, only scale FABQ2 should be used in these groups. The lower proportion of variance accounted for by fearavoidance beliefs in females reflects the generally weaker relationships between any biomedical measures and work loss associated with low back pain in females. There appear to be sex differences not only in work circumstances and attitudes to work but also in interacting family and social factors.

Figure 2 The FABQ provides strong empirical evidence for the fear-avoidance theory. Based on these results it is also possible to form a series of hypotheses for a cognitive-behavioural model of low back disability (Figs. 2-4). Figure 2 is a further development of Loeser’s conceptual model of pain [Loeser 1982] and the Glasgow Illness Model [Waddell et al. 1984]. It offers a biopsychosocial cross-section of the clinical presentation and assessment of chronic pain and disability at one point in time. Fig. 3 compares the different elements of pain and illness behaviour in acute and chronic pain. Fig. 4 considers the major causal pathways postulated between low back pain and disability. Several points may be emphasised.

Throughout, the original physical basis of low back pain is accepted, even if the anatomical site or pathological nature of nociception cannot be identified clinically. From the original definitions, physical impairment may lead directly to disability. In chronic low back pain, however, there may be no evidence of any permanent structural impairment: instead, there is limitation of physical function due to pain [Waddell et al. 1992]. This may be associated with muscle guarding, deranged movement and a disuse syndrome. Chronic pain is sometimes described as persisting beyond normal healing time: if there is no longer any evidence of tissue damage it is sometimes implied that there is no remaining nociception. This would incorrectly imply that there is no longer any sensory component to the pain. This is neither theoretically nor clinically acceptable. Instead, it may be hypothesised that the physiological impairment described above can give rise to musculoskeletal nociception related to physical activity, though this continued nociception now has a very different pathological basis and different implications for treatment.

It should again be emphasised that this study employed a correlational design and the effects of fearavoidance beliefs could only be tested in a longitudinal study or true experimental design. Nevertheless, the model illustrates the various possible roles of cognitive, affective and behavioural factors linking pain, illness behaviour and disability. These may become increasingly important in chronic pain with self-sustaining feed-back. Figure 4 shows the main cognitive pathways postulated between pain and disability, though obviously other cross-links could be postulated and tested. The alternative pathways would allow for the completely different clinical populations seen in highly selected Pain Clinic patients and in medico-legal practice. It should, however, be emphasised that such a biopsychosocial model of low back pain and disability is best regarded as a hypothesis for further empirical testing.

The strength of fear-avoidance beliefs and their powerful relationship to disability has implications for medical management. It may be postulated that current medical advice and treatment for low back pain, and particularly unjustified restriction of activity, the prescription of rest and sick certification by rote [Waddell 1987b], would appear likely to cause or re-inforce fear-avoidance beliefs and hence iatrogenic disability. Changed medical management in this way could even be one of the mechanisms leading to our current epidemic of low back disability [Allan and Waddell 1989]. Physicians and therapists should be aware constantly of the possible central role of fear-avoidance beliefs in the development of chronic incapacity and work loss. Although this study only concerned chronic pain, fear-avoidance beliefs could develop much earlier. To prevent chronicity, such inappropriate fearavoidance beliefs would need to be recognised from the acute stage, tackled directly and changed early before they become fixed. Indeed, it is possible that the first step to successful rehabilitation may be to overcome mistaken fear-avoidance beliefs. Further consideration should be given to the interaction between work-related injury, fear-avoidance beliefs and compensation. Many of these hypotheses should be amenable to empirical testing using the FABQ.

Pain and disability, beliefs and behaviour, medical management: the relationship between them may be the key to understanding the present epidemic of low back disability. Fear-avoidance beliefs merit further study as one of the possible links in a biopsychosocial model of low back pain and disability.Appendix

Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)

Here are some of the things which other patients have told us about their pain. For each statement please circle any number from 0 to 6 to say how much physical activities such as bending, lifting, walking or driving affect or would affect your back pain.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Home and Health Department and The Mactaggart Trust for financial support. Duncan Troup first stimulated our study of fear avoidance. Bill Fordyce, John Hunter, John Loeser, Tom Rudy and Dennis Turk provided helpful comments on an earlier draft.

References:

Allan, D.B. and Waddell, G., An historical perspective on low back pain and disability, Acta Orthop. Stand., 60, Suppl. 234 (1989) l-23.

Bigos, S.J., Battie, M.C., Spengler, D.M., Fisher, L.D., Fordyce, W.E., Hansson, T.H., Nachemson, A.L. and Wortley, M.D., A prospective study of work perceptions and psychosocial factors affecting the report of back injury, Spine, 16 (1991) 1-6.

Cairns, D. and Pasino, J., Comparison of verbal reinforcement and feedback in the operant treatment of disability due to chronic low back pain, Behav. Ther., 8 (1977) 621-630.

Caldwell, A.B. and Chase, C., Diagnosis and treatment of personality factors in chronic low back pain, Clin. Orthop., 129 (1977) 141- 149.

Cohen, J., A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas., 20 (19601 37-46.

Council, J.R., Ahern, D.K., Follick, M.J. and Kline, CL., Expectancies and functional impairment in chronic low back pain, Pain, 33 (1988) 323-333.

Dehlin, 0. and Berg, S., Back symptoms and psychological perception of work: a study among nursing aides in a geriatric hospital, Stand. J. Rehab. Med., 9 (1977) 61-65.

Denny, M.R. (Ed), Fear, avoidance and phobias: a fundamental analysis, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1991.

Dolce, J.J.. Self-efficacy and disability beliefs in behavioural treatment of pain, Behav. Res. Ther., 25 (1987) 289-299.

Dolce, J.J., Cracker, M.F. and Doleys. D.M., Prediction of outcome among chronic pain patients, Behav. Res. Ther., 24 (1986a) 313-319.

Dolce, J.J., Cracker, M.F., Moletteire, C. and Doleys, D.M.. Exercise quotas, anticipatory concern and self-efficacy expectancies in chronic pain: a preliminary report, Pain, 24 (1986bl 3655372.

Dolce, J.J., Doleys, D.M., Raczynski, J.M., Lossie, J., Poole, L. and Smith, M., The role of self-efficacy expectancies in the prediction of pain tolerance, Pain. 27 (1986~1 261-272.

Engel, G.L., Psychogenic pain and the pain prone patient, Am. J. Med., 26 (1959) 899-918.

Fairbank, J.C.T., Mbaot, J.C., Davies, J.B. and O’Brien, J.P., The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, Physiotherapy, 66 (1980) 271-273.

Fleiss, J.L., Cohen, J. and Everitt, B.S., Large sample standard errors of kappa and weighted kappa, Psychol. Bull., 72 (1969) 323-327.

Flor, H. and Turk, D.C., Chronic back pain and rheumatoid arthritis: predicting pain and disability from cognitive variables, J. Behav. Med., 11 (1988) 251-265.

Fordyce, W.E., Behavioural methods for chronic pain and illness, Mosby, St Louis, MO, 1976.

Fordyce, W.E., Pain and suffering: a reappraisal, Am. J. Psycho]., 43 (1988) 276-282.

Fordyce, W.E., Fowler, R.S., Lehmann, J.F. and Delateur, B.J., Some implications of learning in problems of chronic pain, J. Chron. Dis., 21 (1968) 179-190.

Fordyce, W.E., McMahon, R., Rainwater, G., Jackins, S., Questad. K., Murphy, T. and DeLateur, B., Pain complaint-exercise performance relationship in chronic pain, Pain, 10 (1981) 311-321.

Fordyce, W.E., Shelton, J.L. and Dundore, DE., The modification of avoidance learning pain behaviours, J. Behav. Med., 5 (1982) 40.5-414.

Gorsuch, R.L., Factor Analysis. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1974. Jensen, M.P., The Survey of Pain Attitudes, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, 1991.

Jensen, M.P. and Karoly, P., Notes on the Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA): original (24-item) and revised (35-item) versions, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, 1987.

Jensen, M.P., Karoly, P. and Huger, R., The development and preliminary validation of an instrument to assess patient’s attitudes towards pain, J. Psychosom. Res., 31 (1987) 393-400.

Jensen, M.P., Turner, J.A., Romano, J.M. and Karoly, P., Coping with chronic pain: a critical review of the literature, Pain, 47 (1991) 249-283.

Keefe, F.J. and Block, A.R., Development of an observation method for assessing pain behavior in chronic low back pain patients, Behav. Ther., 13 (1982) 363-375.

Landis, J.R. and Koch, G.G., The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data, Biometrics, 33 (1977) 159-174.

Lefebvre, M.F., Cognitive distortion and cognitive errors in depressed psychiatric and low back pain patients, J. Consult. Clin. Psycho]., 49 (1981) 517-525.

Lethem, J., Slade, P.D., Troup, J.D.G. and Bentley, G., Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception, Behav. Res. Ther., 21 (1983) 401-408.

Linton, S.J., The relationship between activity and chronic pain, Pain, 21 (1985) 289-294.

Loeser, J.D., Concepts of pain. In: M. Stanton-Hicks and R. Boas (Eds.), Chronic Low Back Pain, Raven Press, New York, 1982, 145-148.

Lowe, N.K., Walker, S.N. and MacCallum, R.C., Confirming the theoretical structure of the McGill Pain Questionnaire in acute clinical pain, Pain, 46 (1991) 53-60.

Magora, A., Investigation of the relation between low back pain and occupation, Indust. Med., 39 (1970) 504-510.

Main, C.J., The modified somatic perception questionnaire, J. Psychosom. Res., 27 (1983) 503-514.

Main, C.J. and Waddell, G., A comparison of cognitive measures in low back pain: statistical structure and clinical validity at initial assessment, Pain, 46 (1991) 287-298.

Main, C.J., Wood, P.L.R., Hollis, S., Spanswick, C.C. and Waddell, G., The distress and risk assessment method (DRAM): a simple patient classification to identify distress and evaluate the risk of a poor outcome, Spine, 17 (1992a) 42-52.

Main, C.J., Wood, P.L.R., Spanswick, C.C., Roberts, A.P. and Robson, J., The pain locus of control questionnaire, Pain, submitted for publication, 1992b.

Maxwell, A.E., Multivariate statistical methods and classification problems, Br. J. Psychiat., 119 (1971) 121-127.

Mechanic, D., Cleary, P.D. and Greenely, J.R., Distress syndrome, illness behaviour, access to care and medical utilisation in a defined population, Med. Care, 20 (1982) 361-372.

Melzack, R., The McGill pain questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods, Pain, 1 (1975) 277-299.

Melzack, R., The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire, Pain, 30 (1987) 191-197.

Melzack, R. and Casey, K.L., Sensory, motivational and central control determinants of pain. In: D.R. Kenshalo (Ed.), The Skin Senses, Thomas, Springfield, IL, 1968, 423-443.

Melzack, R. and Wall, P.D., Pain mechanisms: a new theory, Science, 150 (1965) 971-979.

Mendelson, G., Psychiatric aspects of personal injury claims, Thomas, Springfield, IL, 1988.

Mendelson, G., Compensation in the maintenance of disability, Eur. J. Pain, 12 (1991) l-11.

Merskey, H., Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Recommended by the IASP Subcomittee on Taxonomy, Pain, 6 (1979) 249-252.

Panksepp, J., Sacks, D.S., Crepeau, L.J. and Abbott, B.B., The psycho- and neuro-biology of fear systems in the brain. In: M.R. Denny (Ed.), Fear, Avoidance and Phobias: a Fundamental Analysis, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1991, 7-59.

Penfield, W.. Foreword. In: J. White and W.H. Sweet, (Eds.), Pain and the Neurosurgeon, Thomas, Springfield, IL, 1969, vii-viii.

Philips, H.C., Avoidance learning and its role in sustaining chronic pain, Behav. Res. Ther., 25 (1987) 273-279.

Pilowsky, I. and Spence, N.D., Patterns of illness behaviour in patients with intractable pain, J. Psychosom. Res., 19 (1975) 279-287.

Pilowsky, I. and Spence, N.D., Manual for the Illness Behaviour Questionnaire (IBQ), 2nd edn., University of Adelaide, 1983.

Pope. M.H., Rosen, J.C., Wilder, D.G. and Frymoyer, J.W., The relation between biomechanical and psychological factors in patients with low-back pain, Spine, 5 (1980) 173-178.

Rachman, S. and Lopatka, C., Accurate and inaccurate predictions of pain, Behav. Res. Ther., 26 (1988) 291-296.

Reesor, K.A., Medically Incongruent Back Pain Presentation: an Indication of Physical Restriction, Suffering and Ineffective Coping with Pain. PhD Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, 1986.

Reesor, K.A. and Craig, K.D., Medically incongruent chronic back pain: physical limitations, suffering and ineffective coping, Pain, 32 (1988) 35-45.

Riley, J.F., Ahern, D.K. and Follick, M.J., Chronic pain and functional impairment: assessing beliefs about their relationship, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab., 69 (1988) 579-582.

Roland, M. and Morris, R., A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I. Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low back pain, Spine, 8 (1983) 141-144.

Rosensteil, A.K. and Keefe, F.J., The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain: relationships to patient characteristics and current adjustment, Pain, 17 (1983) 33-44.

Rudy, T.E., Kerns, R.D. and Turk, D.C., Chronic pain and depression: toward a cognitive-behavioural mediation model, Pain, 35 (1988) 129-140.

Sandstrom, J. and Esbjornsson, E., Return to work after rehabilitation: the significance of the patient’s own prediction, Stand. J. Rehab. Med., 18 (1986) 29-33.

Schmidt, A.J., Cognitive factors in the performance level of chronic low back pain patients, J. Psychosom. Res., 29 (1985) 183-189.

Slade, P.D., Troup, J.D.G., Lethem, J. and Bentley, G., The fear avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception. 11. Preliminary studies of coping strategies for pain, Behav. Res. Ther.. 21 (1983) 409-416.

Slater, M.A., Hall. H.F.. Atkinson. J.H. and Garfin, S.R.. Pain and impairment beliefs in chronic low back pain: validation of the Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale (PAIRS), Pain, 44 (1991) 51-X

Smith. T.W., Follick. M.J., Ahern, D.K. and Adams, A., Cognitive distortion and disability in chronic low back pain. Cogn. Ther. Res., 10 (1986) 201-210.

Strong, J., Ashton, R. and Chant. D., The measurement of attitudes towards and beliefs about pain. Pain, 48 (1992) 227-236.

Troup, J.D.G., The perception of musculoskeletal pain and incapacity for work: prevention and early treatment, Physiotherapy, 74 (1988) 435-439.

Troup. J.D.G.. Foreman. T.K.. Baxter. C.E. and Brown. D., The perception of back pain and the role of psychophysical tests of lifting capacity, Spine, I? (1987) 645-hS7.

Turk, D.C. and Flor, H., Etiological theories and treatments for chronic back pain. II. Psychological models and interventions. Pain, 19 (1984) 209-233.

Turk, D.C., Meichenbaum, D. and Genest, M.. Pain and behavioural medicine, Guildford Press. New York, 1983.

Turk, D.C., Wack, J.T. and Kerns, R.D.. An empirical examination of the pain-behaviour construct, J. Behav. Med., 8 (19%) 119-130.

Turner, J.A. and Romano, J.M.. Cognitive-behavioral therapy. In: J.J. Bonica (Ed.), The Management of Pain, Vol. 2, 2nd edn., Lea and Feabiger, Philadelphia. PA. 1990, 171 l- 1721.

Volinn. E., Van Koevering, D. and Loeser, J.D.. Back sprain in industry: the role of socioeconomic factors in chronicity. Spine, I6 (1991) 542-548.

Waddell, G.. An approach to backache, Br. J. Hosp. Med., 28 (1987) 187-219.

Waddell, G., Clinical assessment of lumbar impairment, Clin. Orthop., 221 (1987a) 110-120.

Waddell. G..

A New Clinical Model For The Treatment Of Low-back Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987 (Sep); 12 (7): 632-644Waddell, G. and Main, C.J., Assessment of severity in low hack disorders, Spine, 9 (1984) 204-208.

Waddell. G. and Richardson, J., Clinical assessment of overt pain behaviour by physicians during routine clinical examination, J. Psychosom. Res., 3h (1991) 77-X7.

Waddell. G.. Main, C.J.. Morris. E.W.. Di Paola, M.P. and Gray, I.C.M.. Chronic low hack pain, psychologic distress. and illness hehaviour. Spine, Y (1984) 209-213.

Waddell, G.. Morris, E.W.. Di Pa&. M.P., Bircher, M. and Finlayson. D.. A concept of illness tested as an improved basis for surgical decisions in low hack disorders. Spine. II (19X6) 712-719.

Waddell, G., Pilowsky. I. and Bond. M.. Clinical assessment and interpretation of abnormal illness behaviour in low hack pain. Pain. 39 (1989) 41-53.

Waddell, G.. Sommerville. D.. Henderson. I. and Newton. M.. Ohjective clinical evaluation of physical impairment in chronic low hack pain. Spine. I7 (1902) 617~628.

Wallston, K.. Wallston, B. and DeVellis. R.. Development of the multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) Scales, Hlth Educ. Monogr., 6 (lY78) IhI--170.

World Health Organisation. International classification of impairments. di?ahilities and handicaps. WHO. Geneva, 1980. 47.

Zung, W.W.K.. A self-rated depression scale, Arch. Gen. Psychiat.. 32 (196.5) 63-70.

Return to OUTCOME ASSESSMENT

Since 10-12-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |