Adverse Events Following Chiropractic Care for Subjects with

Neck or Low-back pain: Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 461464

Sidney M. Rubinstein, DC, PhD

Institute for Research in Extramural Medicine,

EMGO-Institute, VU University Medical Center,

1081 BT Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

sm.rubinstein@vumc.nl

This synopsis provides an overview of the benign and serious risks associated with chiropractic care for subjects with neck or low-back pain. Most adverse events associated with spinal manipulation are benign and self-limiting. The incidence of severe complications following chiropractic care and manipulation is extremely low. The best evidence suggests that chiropractic care is a useful therapy for subjects with neck or low-back pain for which the risks of serious adverse events should be considered negligible.

Key Indexing Terms Chiropractic, Manipulation, Spinal, Adverse Effects, Public Health

From the Article

Background

In comparison with clinical trials on treatment efficacy, much less is known on adverse events after chiropractic care. In general, adverse events after this treatment form for subjects with neck or low-back pain can be divided into 2 categories:(1) benign, self-limiting, and

(2) serious adverse events, such as vertebrobasilar artery (VBA) stroke or cauda equina syndrome.This article will discuss chiropractic care and spinal manipulation, which is the principal mode of therapy delivered by chiropractors. According to international clinical trial terminology, the established term for side effects or adverse treatment reactions is adverse events, and this term will be used in this article. It is meant to encompass both benign and serious events and is not limited to life-threatening events or those requiring hospitalization.

Benign, Self-Limiting Adverse Events

These types of events have been prospectively and systematically described in numerous studies. [16] In general, they are mild to moderate in intensity, have little to no influence on activities of daily living, and recover spontaneously, typically lasting no more than a few days. The complaints, by-and-large, affect the musculoskeletal system, including radiating pain, but also includes other, less common reactions, such as nausea, dizziness, or tiredness. Furthermore, these events seem to be common at the beginning of treatment, most notably after the first treatment, [46] and therefore may have consequences for the plan of treatment.Predictors of Adverse Events Various studies have examined this topic, [2, 79] 2 of which have specifically examined predictors after chiropractic care for neck pain. [7, 8] One study found moderate to severe headache at baseline to be predictive of headache after treatment and a moderate amount of neck disability at baseline to be predictive of developing neck pain/soreness, or neurologic symptoms. [7] Another study found the expressly defined use of cervical rotation during treatment, and working status of the patient (sick leave or workers' compensation), to be moderately associated with an adverse event after any of the first 3 visits. A longer duration of neck pain before treatment was associated with specific types of events, namely, headache or worsening of the presenting neck pain. [8]

Association With Outcome Two studies have examined this topic. [3, 10] One randomized clinical trial (n = 336) concluded that subjects with adverse symptoms were less satisfied with care, perceived less improvement, and had more pain and disability during subsequent follow-up measurements than subjects with no adverse event. [3] In a large prospective cohort study (n = 529), adverse events after any of the first 3 treatments were found to be associated with worse short-term but not worse longer-term outcomes. [10]

Serious Adverse EventsVertebrobasilar Artery Stroke Estimates of VBA stroke after chiropractic care vary widely because they are based on case reports, retrospective studies, or surveys of medical claims data. [11] Consequently, figures on incidence can be extremely unreliable, ranging from 1 serious complication in 200,000 treatments, [12] to 1 in several million cervical spine treatments, [13] or 1 case per 100,000 persons. [14] In an expanded analysis of the Ontario population-based study, which spanned a 9year period representing more than 100 million person-years of observation, only 8 cases of VBA stroke were observed in subjects younger than 45 years exposed to chiropractic care within a week before their stroke. [15] In those older than 45 years, no association was found between chiropractic visits and VBA stroke. It must be noted, however, that there is likely to be a certain amount of imprecision in any of these estimates. [16, 17]

Despite all the case reports, and case series reported in the literature, only 4 (case-control) studies have been identified, which have used a sound study design to allow for the evaluation of the risk of VBA stroke after chiropractic care or spinal manipulative therapy. [14, 15, 18, 19] Three of these studies demonstrated a strong association between chiropractic care/cervical spinal manipulative therapy and stroke, [14, 15, 19] but there is sufficient concern regarding the methodology, such as information and selection bias, and confounding, that these results must be questioned. [20, 21] Furthermore, in one of these recent case-control studies, an equally strong association was found for those who visited the general practitioner during the same period. [15] This would suggest a coincidental rather than causal association and provides stronger evidence for the hypothesis that patients seek care for neck pain or headache due to a VBA stroke in progress. [15]

Cervical Disk Herniation Another perceived serious complication of cervical spine manipulation is the aggravation or precipitation of a disk herniation leading to cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. Data are limited to individual cases and case series. [2225] There is no evidence at this time to suggest that this condition is necessarily a consequence of chiropractic care or spinal manipulation.

Lumbar Disk Herniation and Cauda Equina Syndrome As is the case for the cervical spine, disk herniation after treatment for low-back pain consists exclusively of individual cases and case series. A much less reported phenomenon is cauda equina syndrome. The risk for a serious adverse event, including lumbar disk herniation, has been estimated to be approximately 1 per million patient visits, [22] whereas the incidence for cauda equina syndrome after treatment ranges greatly but is thought to be one in many millions of visits. [22, 24, 26] One systematic review found no serious complications reported in more than 70 controlled clinical trials. [27]

Discussion

This synopsis provides a brief overview of the benign and serious risks associated with chiropractic care for subjects with neck or low-back pain. The evidence cannot be interpreted as demonstrating causality. The lack of a control group in observational research makes it difficult to answer the question whether the effect or outcome would have occurred had the individual not been exposed to the suspected trigger or cause. [28] In randomized clinical trials, individuals are randomly assigned to either the control group or the treated group in an attempt to equally distribute potential confounders among the exposed and nonexposed.

In observational studies, this is obviously not possible, but a methodological hierarchy exists, with case-control and cohort studies providing stronger evidence. Case reports and case series represent weaker evidence because they include only exposed individuals (eg, those who have undergone spinal manipulation) who have developed the target disease, and thus, the lack of a suitable comparison hinders the interpretation. For example, the statement that drinking two glasses of wine a day lengthens a person's life by 4 years is meaningless because it provides no reference category (eg, zero wine consumption). [28] In addition, a temporal association does not imply the causal relationship suggested by case reports. Although various criteria have been established to infer causality, [29] their use is problematic and not without criticism. [3033]

Given that serious adverse events are reported, and that there is a the lack of sufficient studies demonstrating clinically relevant differences in efficacy or long-term differences in outcome, some authors propose that the risks of chiropractic care or spinal manipulation outweigh the potential benefits. [3436] Although a risk-benefit ratio is difficult to calculate, there are a number of systematic reviews that demonstrate that spinal manipulation is superior to placebo or natural course for neck or low-back complaints, [3740] and in some cases when combined with other modalities, such as exercise, also superior to standard treatment options in the short term for those with acute or chronic pain. [41, 42] The vast majority of adverse events, however, are benign and self-limiting, and the incidence of severe complications after chiropractic care/manipulation is extremely low.

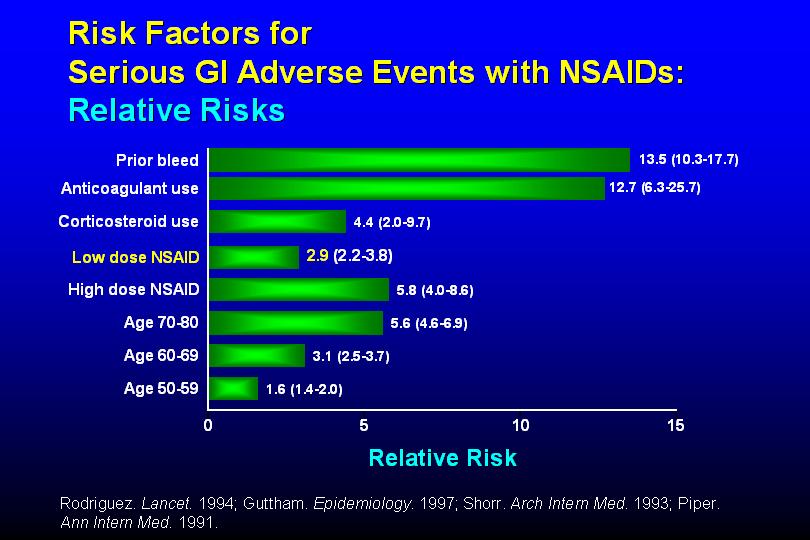

It is perhaps necessary to place this subject in relation to other commonly applied therapies for neck and low-back pain, namely, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). It is estimated that more than 30 million people take NSAIDs daily for the treatment of pain and inflammation. [43] A recent update of the Cochrane review on NSAIDs use for low-back pain concludes that although they are effective for short-term symptomatic relief for acute and chronic low-back pain without sciatica, the effect sizes are small. [44] Furthermore, both cyclooxygenase (COX), COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors are known to cause toxic gastrointestinal effects, [45, 46] with an estimated 2.5 million people in the United States annually experiencing adverse renal effects caused by the use of these medications. [47] Comparative estimates suggest that the risk with NSAID use is much greater than with manipulation [40, 48]; however, any direct comparisons with adverse effects after manipulation are difficult because, for example, NSAIDs are taken for a wide variety of painful and inflammatory or arthritic conditions, for which benefits of chiropractic care might also be debated. Thus, it would seem that the population undergoing chiropractic care is a probable subset of those taking NSAIDs. Furthermore, as has been noted elsewhere, it is meaningless to compare figures based on exposure after a limited number of spinal manipulation sessions to prolonged exposure to medication use. [49] Clearly, future work is necessary to resolve this issue.

References:

Barrett AJ, Breen AC

Adverse effects of spinal manipulation.

J R Soc Med. 2000; 93: 258-259Cagnie B, Vinck E, Beernaert A, et al.

How Common Are Side Effects of Spinal Manipulation

And Can These Side Effects Be Predicted?

Manual Therapy 2004 (Aug); 9 (3): 151156Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Vassilaki M et al.

Adverse reactions to chiropractic treatment and their effects on satisfaction and clinical outcomes

among patients enrolled in the UCLA Neck Pain Study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004; 27: 16-25Leboeuf-Yde C, Hennius B, Rudberg E et al.

Side effects of chiropractic treatment: a prospective study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997; 20: 511-515Rubinstein SM, Leboeuf-Yde C, Knol DL, de Koekkoek TE,

Pfeifle CE, van Tulder MW.

The Benefits Outweigh the Risks for Patients Undergoing Chiropractic

Care for Neck Pain A Prospective, Multicenter, Cohort Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Jul); 30 (6): 408418Senstad O, Leboeuf-Yde C, Borchgrevink C

Frequency and characteristics of side effects of spinal manipulative therapy.

Spine. 1997; 22: 435-440Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Vassilaki M et al.

Frequency and clinical predictors of adverse reactions to chiropractic care in the UCLA neck pain study.

Spine. 2005; 30: 1477-1484Rubinstein SM, Leboeuf-Yde C, Knol DL et al.

Predictors of adverse events following chiropractic care for patients with neck pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008; 31: 94-103Senstad O, Leboeuf-Yde C, Borchgrevink C

Predictors of side effects to spinal manipulative therapy.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996; 19: 441-445Rubinstein SM, Knol DL, Leboeuf-Yde C, van Tulder MW.

Benign Adverse Events Following Chiropractic Care for

Neck Pain Are Associated With Worse Short-term

Outcomes but Not Worse Outcomes at Three Months

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 (Dec 1); 33 (25): E950956Thiel HW, Bolton JE, Docherty S, Portlock JC:

Safety of Chiropractic Manipulation of the Cervical Spine: A Prospective National Survey

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 (Oct 1); 32 (21): 23752378Michaeli A

Reported occurrence and nature of complications following manipulative physiotherapy in South Africa.

Aust J Physiother. 1993; 39: 309-315Haldeman S, Carey P, Townsend M, Papadopoulos C.

Arterial Dissections Following Cervical Manipulation: The Chiropractic Experience

Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) 2001 2001 (Oct 2); 165: 905906Rothwell DM, Bondy SJ ,Williams JI

Chiropractic manipulation and stroke: a population-based case-control study.

Stroke. 2001; 32: 1054-1060Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Cote P, et al.

Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care: Results of a Population-based

Case-control and Case-crossover Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S176183Hanley JA Lippman-Hand A

If nothing goes wrong, is everything all right? Interpreting zero numerators.

JAMA. 1983; 249: 1743-1745Ho AM Dion PW Karmakar MK et al.

Estimating with confidence the risk of rare adverse events, including those with observed rates of zero.

Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002; 27: 207-210Dittrich R Rohsbach D Heidbreder A et al.

Mild mechanical traumas are possible risk factors for cervical artery dissection.

Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007; 23: 275-281Smith WS Johnston SC Skalabrin EJ et al.

Spinal manipulative therapy is an independent risk factor for vertebral artery dissection.

Neurology. 2003; 60: 1424-1428Rubinstein S Cote P

Mild mechanical traumas are possible risk factors for cervical artery dissection.

Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007; 24: 319Rubinstein SM Peerdeman SM van Tulder MW et al.

A systematic review of the risk factors for cervical artery dissection.

Stroke. 2005; 36: 1575-1580Assendelft WJ Bouter LM Knipschild PG

Complications of spinal manipulation: a comprehensive review of the literature.

J Fam Pract. 1996; 42: 475-480Malone DG Baldwin NG Tomecek FJ et al.

Complications of cervical spine manipulation therapy: 5-year retrospective study in a single-group practice.

Neurosurg Focus. 2002; 13: ecp1Oppenheim JS Spitzer DE Segal DH

Nonvascular complications following spinal manipulation.

Spine J. 2005; 5: 660-666Tseng SH Lin SM Chen Y et al.

Ruptured cervical disc after spinal manipulation therapy: report of two cases.

Spine. 2002; 27: E80-E82Haldeman S Rubinstein SM

Cauda equina syndrome in patients undergoing manipulation of the lumbar spine.

Spine. 1992; 17: 1469-1473Meeker, W., & Haldeman, S. (2002).

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216227Greenland S Morgenstern H

Confounding in health research.

Annu Rev Public Health. 2001; 22: 189-212Hill A

The environment and disease: association or causation?.

Proc R Soc Med. 1965; 58: 295-300Charlton BG

Attribution of causation in epidemiology: chain or mosaic?

J Clin Epidemiol. 1996; 49: 105-107Hofler M

The Bradford Hill considerations on causality: a counterfactual perspective.

Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2005; 2: 11Phillips CV Goodman KJ

The missed lessons of Sir Austin Bradford Hill.

Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2004; 1: 3Rothman KJ Greenland S

Causation and causal inference in epidemiology.

Am J Public Health. 2005; 95: S144-S150Ernst E Assendelft WJ

Chiropractic for low back pain. We don't know whether it does more good than harm.

BMJ. 1998; 317: 160Ernst E.

Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulation: A Systematic Review

J R Soc Med. 2007 (Jul); 100 (7): 330338Williams LS Biller J

Vertebrobasilar dissection and cervical spine manipulation A complex pain in the neck.

Neurology. 2003; 60: 1408-1409Assendelft WJ Morton SC Yu EI et al.

Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; : CD000447Bronfort G Haas M Evans RL et al.

Efficacy of Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization for Low Back Pain and Neck Pain:

A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis

Spine J (N American Spine Soc) 2004 (May); 4 (3): 335356Chou R, Huffman LH; American Pain Society.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 492504Hurwitz EL, Aker PO, Adams AH, Meeker WC, Shekelle PG.

Manipulation and Mobilization of the Cervical Spine:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996 (Aug 1); 21 (15): 17461760Gross AR Hoving JL Haines TA et al.

A Cochrane review of manipulation and mobilization for mechanical neck disorders.

Spine. 2004; 29: 1541-1548Underwood M, UK BEAM Trial Team.

United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) Randomized Tial:

Effectiveness of Physical Treatments for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 13771384Singh G Triadafilopoulos G

Epidemiology of NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications.

J Rheumatol Suppl. 1999; 56: 18-24Roelofs PD Deyo RA Koes BW et al.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; : CD000396Kargman S Charleson S Cartwright M et al.

Characterization of prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 and 2 in rat, dog, monkey, and human gastrointestinal tracts.

Gastroenterology. 1996; 111: 445-454Ofman JJ MacLean CH Straus WL et al.

A meta-analysis of severe upper gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

J Rheumatol. 2002; 29: 804-812Sandhu GK Heyneman CA

Nephrotoxic potential of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors.

Ann Pharmacother. 2004; 38: 700-704Dabbs V Lauretti WJ

A Risk Assessment of Cervical Manipulation vs. NSAIDs for the Treatment of Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1995 (Oct); 18 (8): 530536Stevinson C Ernst E

Risks associated with spinal manipulation.

Am J Med. 2002; 112: 566-571

Return to ADVERSE EVENTS

Since 4-24-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |