Implications of Placebo and Nocebo Effects

for Clinical Practice: Expert ConsensusThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2022 (Oct 21); 62: 102677 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS David Hohenschurz-Schmidt, Oliver P Thomson, Giacomo Rossettini, Maxi Miciak, Dave Newell, et al

Pain Research, Dept. Surgery & Cancer,

Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College,

Chelsea & Westminster Hospital Campus,

369 Fulham Road London,

London, SW10 9NH, UK.

Introduction: While the placebo effect is increasingly recognised as a contributor to treatment effects in clinical practice, the nocebo and other undesirable effects are less well explored and likely underestimated. In the chiropractic, osteopathy and physiotherapy professions, some aspects of historical models of care may arguably increase the risk of nocebo effects.

Purpose: In this masterclass article, clinicians, researchers, and educators are invited to reflect on such possibilities, in an attempt to stimulate research and raise awareness for the mitigation of such undesirable effects.

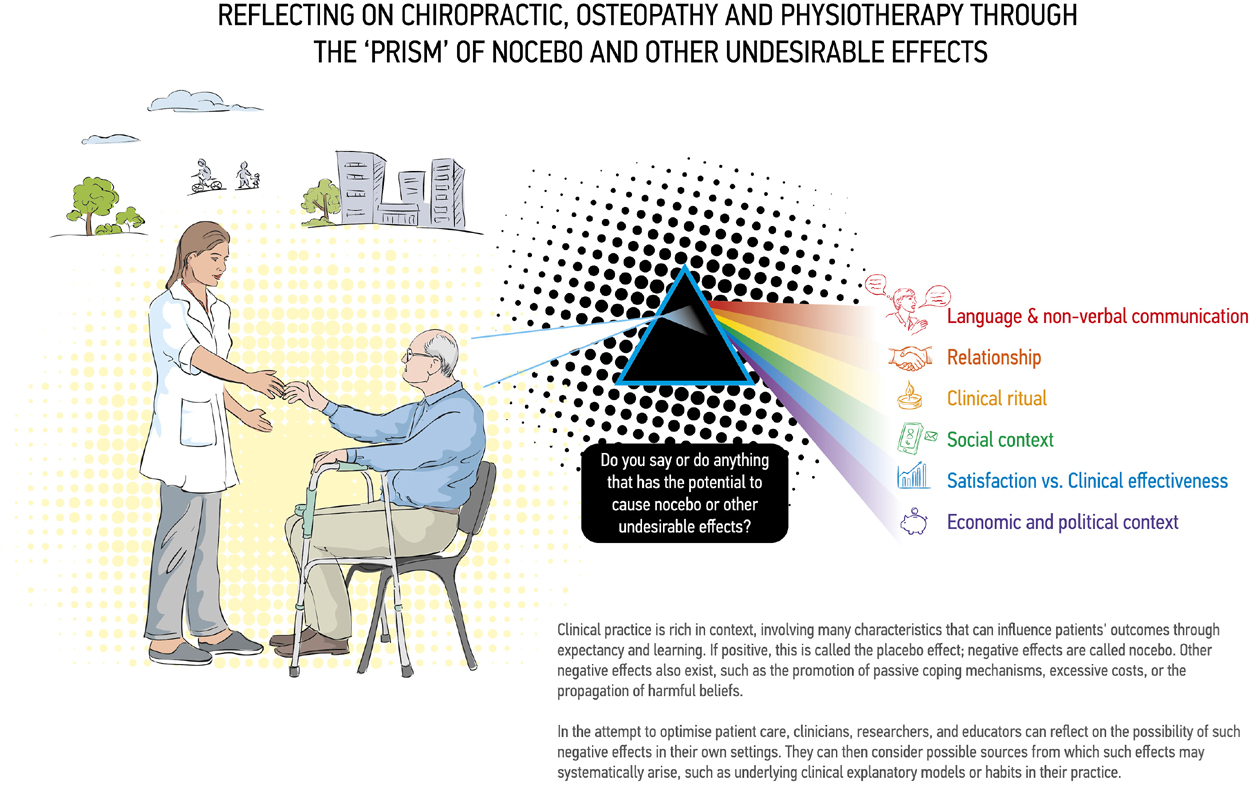

Implications: This masterclass briefly introduces the nocebo effect and its underlying mechanisms. It then traces the historical development of chiropractic, osteopathy, and physiotherapy, arguing that there was and continues to be an excessive focus on the patient's body. Next, aspects of clinical practice, including communication, the therapeutic relationship, clinical rituals, and the wider social and economic context of practice are examined for their potential to generate nocebo and other undesirable effects. To aid reflection, a model to reflect on clinical practice and individual professions through the 'prism' of nocebo and other undesirable effects is introduced and illustrated. Finally, steps are proposed for how researchers, educators, and practitioners can maximise positive and minimise negative clinical context.

Keywords: Adverse events; Manual Therapy; Nocebo; Physiotherapy.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction - The nocebo effect as a problem

Table 1 Placebo and nocebo effects are changes in clinical outcomes due to patient expectations or subconscious learning, produced by treatment context rather than the typically considered ‘active’ element of an intervention. While placebo effects produce positive changes, nocebos are negative (Evers et al., 2018). The placebo effect is a recognised contributor to the effectiveness of many therapies (Tuttle et al., 2015; Wartolowska et al., 2017; Vollert et al., 2020; Bosman et al., 2021; Cashin et al., 2021; Tsutsumi et al., 2022), including manual and physical interventions for people experiencing musculoskeletal pain and other conditions (Bialosky et al., 2009, 2017; Chaibi et al., 2017; Dougherty et al., 2014). Expert consortia recommend using the placebo effect to enhance the real-world effectiveness of medical interventions and state the need to minimise nocebo effects (Evers et al., 2018) (Table 1).

However, this paper argues that nocebo and other undesirable effects of treatment contexts have not been sufficiently researched. Their full complexity and relevance to clinical practice are potentially underestimated, particularly given that nocebo effects are likely easier to elicit and more impactful than placebo effects (Amanzio et al., 2009; Petersen et al., 2014; Greville-Harris and Dieppe, 2015).

Importantly, chronic primary pain patients are arguably particularly vulnerable to nocebo effects due to previous experiences and other influences that may promote negative expectations in a treatment context (Locher et al., 2019). We propose that the prevalent conceptual models in chiropractic, osteopathy, and physiotherapy (COP) hold significant potential for negative cueing of contextual factors within therapeutic encounters and consequently nocebo and other undesirable effects.

Like the placebo effect, nocebo effects are mainly mediated through learning and expectation mechanisms acting through descending pain modulatory pathways (Kleine-Borgmann and Bingel, 2018; Benedetti and Piedimonte, 2019; Colloca and Barsky, 2020; Benedetti et al., 2022). In the narrowest sense, nocebo hyperalgesia is the aggravation of pain not due to disease or treatment-inherent factors, but treatment context (Evers et al., 2018) (Table 1). Other nocebo effects can be the experience or aggravation of treatment side-effects, likely tiredness or soreness after COP treatments (Leboeuf-Yde et al., 1997) (although mild side effects may enhance treatment effects via expectancy mechanisms (Berna et al., 2017)).

Figure 1

Table 2 In a broader sense, however, context-dependent negative effects of patient-practitioner interactions go beyond immediate symptom aggravation and include learnt helplessness, fear avoidance, over-reliance on medical care, and other negative sequelae explored below. Although occasionally the mechanisms of classical nocebo effects may be implicated, behavioural and social mechanisms dominate. In particular, behavioural components likely contribute to negative outcomes that arise when biomedico-structural explanatory frameworks are communicated between practitioners and patients, but also in society at large (Table 1).

There remains a need to explicitly identify and evidence the impact of nocebic elements within therapeutic encounters, and assess how these may be the result of profession-specific explanatory frameworks (Figure 1, Table 2). The purpose of this masterclass is to raise awareness of such explanatory frameworks amongst clinicians and educators and their potential impact on clinical interactions; and to highlight the need for further investigation to avoid undesirable effects on patients seeking care.

The context-sensitivity of treatment outcomes

Clinical outcomes are context-sensitive: Placebo research has illustrated the powerful impact of patient and practitioner characteristics and beliefs, the healthcare setting, treatment characteristics, and the patient–practitioner interaction (O'Keeffe et al., 2016; Bishop et al., 2017; Benedetti et al., 2018). Clinical practice in COP is often highly participatory, involving the sharing of patients' narratives, verbal and non-verbal communication with practitioners, and physical interactions, including through touch (Roberts and Bucksey, 2007; Kim et al., 2022).

Musculoskeletal practitioners make person/patient-specific judgements, where the solutions to clinical problems are often ambiguous, ill-defined, and not always amenable to the routine use of technical skills and propositional knowledge (Petty et al., 2012; Thomson et al., 2014). Furthermore, practitioners' interactions with patients and the cues they deliver co-create meaning within the healthcare encounter (Hutchinson and Moerman, 2018; Stilwell and Harman, 2019), also interacting with an individual's previous experiences (Newell et al., 2017) and the wider societal context. Patients may adapt how they behave, think, and experience their condition in accordance with these meanings.

Due to the contextually rich nature of the therapeutic encounter in COP, many authors recommend enhancing clinical outcomes through honing of contextual aspects that are under the practitioner's control (Testa and Rossettini, 2016; Bialosky et al., 2017; Evers et al., 2018; Manaï et al., 2019). In these publications, however, the recommendations to avoid nocebo effects are largely a mirror image of the attempt to ‘boost’ placebo effects: For example, where empathic communication is recommended to enhance placebo effects, de-validating communication should be avoided as it may lead to nocebo effects (Greville-Harris and Dieppe, 2015; Rossettini et al., 2020a, 2022).

Albeit relevant, we argue that this approach is insufficient. Instead, we propose that features inherent in their historical development and underpinning explanatory frameworks make COP professions prone to generating nocebo and other undesirable effects in a systematic fashion. Similar attempts for investigation have been made in psychotherapy (Locher et al., 2019).

COP foundational knowledge: Focussing on the patient body

Body-mind dualism shaped most thinking about health and disease in western societies, and continues to influence patient expectations and medical decision-making (Demertzi et al., 2009; Hofmann, 2016). Musculoskeletal care has an inherent focus on the patient's body, indeed embedded in its name. The biopsychosocial model was proposed over 45 years ago (Engel, 1981) and while professional training and education may be increasingly incorporating psychosocial perspectives, clinical practice is still dominated by physically-focused approaches (Cowell et al., 2018; Macdonald et al., 2018; Oostendorp et al., 2015; Thomson et al., 2014). These approaches rely mostly on biomedical assumptions that are deeply ingrained in COP training (Gliedt et al., 2020) and professional identity.

Scientific interest in the human spine's role in health and disease dates back to ancient times (Sanan and Rengachary, 1996), but merged with Descartes' mechanical philosophy in the 17th century, powerfully postulating that “all of animal physiology could be explained by mechanics.” (Naderi et al., 2007). Explicitly referring to the notion of ‘the body as a machine’, osteopathy's founder, A.T. Still, incorporated this philosophy into his understanding of illness and therapy, with the osteopath as the ‘mechanic’ who tests the machine for signs of stress, strain, and deviations from the norm to then manually correct those ‘lesions’ (Liem, 2016; Still, 1908). From their inception, influences from spiritual vitalism and naturopathy are apparent in osteopathy and chiropractic. Nonetheless, such influences only led osteopaths to relocate the mechanical ‘fulcrum’ to the energetic realm (e.g., ‘biodynamics’) and chiropractors to ‘remove neuromechanical interference’ to facilitate the metaphysical flow of a universal life force (Simpson and Young, 2020). Mechanistic principles continue to dominate the teaching in craniosacral therapies (Liem, 2009; Sergueef, 2007) and chiropractic (Marcon et al., 2019).

Explanatory frameworks in physiotherapy were influenced by regional phenomena, such as gymnastics, massage, and naturopathic traditions in Germany and Scandinavia (Hüter-Becker, 2004; Schiller, 2021) or the rehabilitation of injured soldiers in wartime Britain and the U.S. Furthermore, the quest for scientific validation in the 20th century (Nicholls, 2017) and a strong link to athletic performance science promoted the extensive measurement and classification of the body's structure and function. Throughout the 20th century, the COP professions have played their part in promoting a ‘compulsory able-bodiedness’, the hegemonic preferability of ableness at the expense of supposedly ‘abnormal’ people, including people living with some form of ‘disability’ or the normal effects of ageing (MacMillan, 2021; McRuer, 2010). For example, manual therapists and their institutions have at times promoted an obsession with ‘good posture’ (Hüter-Becker, 2004; Linker, 2005, 2021). Contemporary trends such as fascia-based concepts (Myers, 2012; Tozzi, 2012) or functional biomechanics (“Gray Institute - Blog,” n.d.) are modern manifestations of an excessive focus on physicality and of a continuing body-mind dualism. Chiropractic Functional Neurology, an approach characterised by the finding and fixing of functional neurological ‘lesions’, alludes to the same mechanical ‘tweaking’ but at nerve level (Meyer et al., 2017). Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary (Lederman, 2011), the notion of normative body-mechanics is deeply embedded in the COP professions' teaching models. As we argue below, this may underpin many undesirable effects of COP practice.

Examining clinical COP practice for potential nocebo and other undesirable effects

In the case of COP, nocebo effects have been attributed to contextual factors, briefly reviewed below (also Table 1). We add to the discussion behavioural features of practitioners and patients, also broadening the perspective by not only looking at pain and function in relation to nocebo effects but adding upstream mediators of poor health outcomes and a socioeconomic discussion of incentive structures.

The role of language and nonverbal communication

In the area of language, there are attempts to acknowledge the link between the nocebo effect and common clinical reasoning frameworks of COP practitioners. Stewart and Loftus (2018) promote “an improved understanding of the frequently hidden influence that language can have on musculoskeletal rehabilitation” (p.519) and draw attention to the fact that potentially harmful language may be linked to underlying concepts of health and disease. Especially, reconceptualising pain as a complexly influenced and emergent phenomenon rather than a linear consequence of tissue damage is warranted. A meta-analysis suggests that effect sizes related to verbally induced nocebo can be substantive (Petersen et al., 2014). Verbal cues can be either specifically designed as negative (“this will be painful”, as in experiments) or incidental within clinical settings such as the use of negative words to describe a non-threatening situation; for example, diagnostic descriptions of imaging reports perceived by patients as implying an increased severity of their condition (Farmer et al., 2021).

Importantly for this discussion, COP vocabulary is replete with terms that medicalise normal anatomy (‘lesion’, ‘dysfunction’, ‘subluxation’, ‘asymmetry’, ‘scoliosis’, ‘blockage’, etc.) and physiological processes (e.g., ‘degeneration’). The negative impact of diagnostic labels has been further shown amongst patients experiencing low back pain: diagnostic labels which allude to specific pathoanatomy (e.g., ‘joint degeneration’ or ‘disc bulge’) led to more imaging and second-opinion consultations compared to those de-emphasizing anatomical structures and damage (e.g., ‘episode of back pain’, ‘lumbar sprain’, and ‘non-specific low back pain’)(O'Keeffe et al., 2022). Such reconceptualization is the aim of several biopsychosocial management strategies for patients with musculoskeletal pain (Leventhal et al., 2016; Carnes et al., 2017; Keefe et al., 2018; O'Sullivan et al., 2018; Ashar et al., 2021), most strikingly expressed in pain education approaches (Moseley and Butler, 2015; Traeger et al., 2018). Educating patients in an evidence-based manner is also concordant with many patients' desire for explanation and diagnosis (McRae and Hancock, 2017 ). If a definite ‘label’ is desired by the patient, it nonetheless needs to be evidence-based and can be complemented by reassurance and education.

The not-so-therapeutic relationship

The therapeutic relationship is the shared affective affinity between practitioner and patient, formed by establishing personal and professional connections within a safe environment (Miciak et al., 2018, 2019; McCabe et al., 2021). Albeit often assumed to be inherently beneficial, therapeutic relationships are complex social endeavours in which patients and clinicians are continually responding and reacting to a slew of emergent personal (e.g., emotions, expectations), intersubjective (e.g., power dynamics), and institutional (e.g., performance measures) factors. Given this complexity, ruptures are expected consequences of therapeutic relationships (Gelso and Kline, 2019; Miciak and Rossettini, 2022; Safran and Kraus, 2014). Ruptures are relational tensions that range from minor rifts to major breaches (Gelso and Kline, 2019; Safran and Kraus, 2014). Ruptures are implicit to all relationships, therapeutic or otherwise. Their presence within the clinical encounter implies nocebo effects (Blease, 2022) and nonadherence.

COP professional ways of practicing can cause relational ruptures. Although biopsychosocial and person-focused care models are promoted as ‘the way’ to practise (Gibson et al., 2020; Hutting et al., 2022), and would seem to mitigate relational breakdowns (Ekman et al., 2011), implementation is often conflicted, inconsistent, or mechanised (Ekman et al., 2011; Synnott et al., 2015; Cowell et al., 2018; Ng et al., 2021; Gibson et al., 2020). Clinicians' failure to connect with patients in a humanistic way (Gibson et al., 2020; Godfrey, 2020) or acknowledge the influence of their own emotional reactions on clinical decisions (Langridge et al., 2016; Miciak and Rossettini, 2022), could result in patients withdrawing from or becoming confrontational with clinicians, which if unaddressed can negatively influence the therapeutic process and clinical outcomes (Safran and Kraus, 2014). Further, disagreements on goals (Miciak and Rossettini, 2022) and potentially unmet patient expectations (Schemer et al., 2020) may cause ruptures. This is why Nijs et al. (2013) recommend exploring patients' attitudes and beliefs as the basis for clinical decision-making and the addressing of false beliefs.

Similarly, professional ‘scripts’, although efficient, can trigger such tensions when incongruent with patient needs. Scripts are professionally sanctioned ways of engaging based on ‘written and unwritten’ (Gibson et al., 2020) texts, such as best practice guidelines, outcome measures, and documentation practices (Gibson et al., 2020). In COP, most such scripts remain biomechanically focused (Cowell et al., 2018; Macdonald et al., 2018; Oostendorp et al., 2015; Thomson et al., 2014). Even clinicians trained in psychosocially oriented approaches to care might default to such scripts when they feel uncomfortable within the clinical interaction or need to be validated professionally. For example, clinicians under duress may automatically revert to biomedical aspects of care, become transactional versus relational in their approach, or engage in paternalistic ways of being (Ekman et al., 2011; Gibson et al., 2020; May et al., 2004).

Therapeutic relationships can empower or disempower patients in their experience of pain by cultivating a sense of safety or threat with and within their own bodies (Arandia and Di Paolo, 2021; Miciak et al., 2019). This may foster expectancies about symptom development, although the direction of the effect may depend on the specific example (Peschken and Johnson, 1997; McMurtry et al., 2006; Pincus et al., 2013). Safety as a function of relationships is ingrained in social hierarchies. For example, children gain trust in themselves when parents show trust in them (Ryan et al., 1994; Otto and Keller, 2014; Brummelman et al., 2019). A child trying to balance the branch of a tree is looking to their parent for encouragement and is more likely to hesitate or even fall if they are met with a worried expression (Gershgoren et al., 2011) - as would be the case if the parent thinks the branch might break at any point. The socially learnt expectation of threat or safety is a key mediator in placebo and nocebo effects, making improvement or deterioration more likely, respectively (Arandia and Di Paolo, 2021). Like a child to their parents, patients look to their clinician for an indication of safety or danger, for example when performing a movement, likely more so when the provider has fostered a hierarchical paternalistic relationship as is inherent in traditional COP thinking.

The clinical ritual

COP are highly ritualistic therapies, often with treatments delivered in clinical settings full of symbols of health and life, through repeated visits, routine ‘skilful’ examination, and treatment methods that convey professional and clinical expertise (Kaptchuk, 2011). This ritual is often accompanied by visible totems of hierarchised specialisation and expertise which the patient is invited to trust (titles, certifications, anatomical wall charts and models). At home, and like a reminder of the ritual, patients are encouraged to perform little rituals themselves (e.g., exercises). There is not necessarily any harm in such rituals. Indeed, they are part and parcel of all medical interventions, western or otherwise, and science is beginning to recognise their healing potential (Jonas, 2018). However, while these rituals are supposed to mean ‘healing’ (Hutchinson and Moerman, 2018), their meaning is open to interpretation. Rituals can become problematic in various scenarios: When they are elevated to represent the only possible source to alleviate somebody's suffering, they can create dependency and potential for exploitation. An example is the idea of ‘killer subluxations’ which can only be removed by chiropractors (Carter, 2000). Also, clinicians need to be aware of the possibility of adverse conditioning, including from previous experiences with COP (Locher et al., 2019).Social learning and the social context of practice

Social learning is strong (Sorensen, 2006) and COP clinicians regularly drive nocebic learning. YouTube content with men in white coats wielding a plasticine model of a spine whilst red flashes indicate the ‘source’ of the pain, may have more views than most public outreach campaigns, undoing valuable educational work (Maia et al., 2021; Hornung et al., 2022). These social media agitators, together with the disciples of traditionalist or secular schools of musculoskeletal care, keep the circles of social learning going. Indeed, this may constitute a negative social contract between patients and the treating professions, where outdated beliefs are kept alive and erroneous models communicated continuously by professionals to patients; the effect being that these explanatory frameworks then drive demand by patients. Together with their often appealingly simplistic logic, the continued spreading of such narratives ensures that an individual's symptomatic improvement is ascribed to the treatments – again perpetuating false beliefs.

Satisfaction does not equal effective care

Patient satisfaction with COP is high but does not correlate clearly with effectiveness: in a UK osteopathy survey, about 90% of patients were satisfied one week after their treatment with only 3% describing themselves as recovered (Fawkes and Carnes, 2021) (Also see Field and Newell (2016)). Satisfaction and clinical effectiveness interact in complex ways (Chen et al., 2019; Rossettini et al., 2020b), and arguments for the value of patient satisfaction are increasingly made (Morris et al., 2013; Tinetti et al., 2016). In private COP practice and elsewhere, however, incentives exist for practitioners to mainly provide what is likely to satisfy patients, not what constitutes evidence-based care. As outlined above, prevalent COP explanatory frameworks may facilitate such decision-making. Examples include patients preferring a ‘simple’ mechanistic diagnosis or patients with uncomplicated primary low back pain demanding (referral for) imaging (Blokzijl et al., 2021; Jenkins et al., 2016, 2018a): The clinician can decide to not satisfy the patient's wish, thus acting in line with current evidence, or to comply and risk nocebo effects from relational ruptures or incidental imaging findings (Kendrick et al., 2001; Rajasekaran et al., 2021). Importantly, satisfaction may increase healthcare costs and contribute to worse clinical outcomes, including mortality (Fenton et al., 2012), although the evidence is conflicting (Anhang Price et al., 2014). Therefore, despite potential benefits, satisfaction should not be used as a proxy for effectiveness nor dominate clinical decision-making. Future research should evaluate its relationship with COP concepts and low-value care (Moynihan et al., 2012), and how clinicians can best negotiate patient expectations that conflict with evidence.

The economic context of clinical practice

Physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain, in particular, can be delivered at relatively low cost individually or in group settings, potentially facilitating physiotherapy's integration into many public healthcare systems. Contrastingly, osteopathy and chiropractic are practised almost exclusively in private settings (“Chiropractic,” 2017; “Osteopathy,” 2017). However, compared to many biomedical interventions for pain, these are still relatively low-cost interventions, posing the question of why their integration into healthcare systems is not more advanced. While there are quality concerns with underlying efficacy and effectiveness research (Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2021b, 2022a), spinal manipulation-based interventions, for example, show some beneficial effects, and underlying sham-controlled studies are plentiful (Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2022b; Rubinstein et al., 2019). Therefore, the focus on private practice models may have additional reasons, and, apart from historical reasons, underlying thought models are a likely culprit: Concepts in osteopathy and chiropractic imply long-term treatment, including in the absence of symptoms – an approach that decision-makers in public healthcare systems are unwilling to support. Conversely, these models may appeal to people who can or would like to afford externalising responsibility for their health to practitioners.

Maintenance care is an example of patient passivity even in the absence of symptoms. It is common practice in osteopathy and chiropractic (Axén et al., 2019), probably mainly in pockets of the professions that adhere to traditional schools of thought (Gíslason et al., 2019). Although Eklund et al. (2018) have shown comparable effects for maintenance visits and symptom-driven visits in patients with persistent low back pain, these authors acknowledged the possibility that positive outcomes associated with ongoing visits could result from meeting and interacting with the clinician rather than the spinal manipulative therapy itself. While there are some arguments for regularly ‘checking in’ with a healthcare professional (Axén et al., 2019; Volz et al., 2021), maintenance concepts may over-emphasise reliance on others rather than promoting health through self-management and a healthy lifestyle. At the same time, biomedical models of disease obscure socio-political causes of disease (Kriznik et al., 2018; Marmot, 2020) - an effect, however, that can be criticised in the biopsychosocial model or behavioural interventions, too (Nunan et al., 2021; Shakespeare et al., 2017). In addition, passive approaches may further increase the divide between those able to self-fund COP therapies and those who cannot: By blending into private practice business models that depend on returning patients for income, biomedical thinking turns otherwise relatively low-cost healthcare into an exclusive provision to those able to afford a series of appointments (McGill et al., 2015; Nunan et al., 2021), as reflected by the demographic profiles of patients seeking chiropractic (Beliveau et al., 2017; Herman et al., 2018; Mior et al., 2019) and osteopathic care (Burke et al., 2013; Fawkes et al., 2014; Alvarez Bustins et al., 2018; Fawkes and Carnes, 2021). Ideally, COP act as advocates for patients, lobbying for availability of evidence-based interventions, integration with public services, and reduction of socioeconomic disparities (Nunan et al., 2021).

Making the most of COP: Maximising placebo and minimising harm

COP are well-placed to provide primary health care that reduces requests for imaging, strong analgesic medications, and invasive pain treatments, and to mitigate the commonly-held belief that where there is pain there must be an injury. COP practitioners could do so by triaging, providing patient-focussed communication and supportive relationships, helping to re-engage in physical activity and providing short-term symptom relief, and by increasing their focus on advocacy for patients. To effectively redirect patients’ journeys away from provider-shopping and consecutive disappointments, long-term educational efforts at profession-level need to be paired with public outreach campaigns and the disincentivizing of passive low-value care.

The first step: Raising awareness

For too long, the placebo effect was seen as an undesirable nuisance or somewhat impure means of enhancing health outcomes. Trying to overcome this aversion, researchers are now communicating that placebo effects are inherent, neurophysiologically grounded parts of healthcare (Evers et al., 2021), likely more so in inherently social and complex interventions such as COP (Rossettini et al., 2020a; Testa and Rossettini, 2016). These effects should be embraced rather than dismissed (Evers et al., 2018; Kleine-Borgmann and Bingel, 2018). Indeed, COP curricula now place more emphasis on relationship-building and communication skills.

Nonetheless, a similar shift in awareness cannot be observed with regards to nocebo effects. Contrary to placebo effects, they do not need to be positively reframed. Quite the opposite, they may have to be actively demonised, owing to their potential for harm (and barring the need for further research). Initiatives for change need to address multiple levels: practitioners and students, educational institutions, healthcare systems and policy makers, and the public. Often, clinicians will find contextual factors easily modifiable, for example by adjusting the wording of a prognosis or avoiding negative behaviours (e.g., frowning at the sight of a person's not-so-straight back). Contemporary academic discussions of COP have largely overcome structural models of health and disease (Alvarez et al., 2021; Bialosky et al., 2009; Draper-Rodi et al., 2018; Esteves et al., 2020; Hutting et al., 2022; Lederman, 2017; Stilwell and Harman, 2019) and can be used to design awareness campaigns. Irrespective of the impact of these behaviours on the patient, following these suggestions will make for a more positive atmosphere in the clinic as contemporary practice becomes less influenced by traditional COP concepts.

To aid reflection, we propose to consider clinical practice and individual professions through the ‘prism’ of nocebo and other undesirable effects (Fig. 1), also drawing on content of Table 2.

The second step: Research

With the explosion of the placebo research field (JIPS database, n.d.), research into nocebo effect has also increased. So far, the evidence indicates that nocebo effects can be powerful under certain circumstances, with some studies providing conflicting evidence (e.g., Coleshill et al., 2021). When studied not in a purely experimental setting, however, the evidence is clear that contextual factors such as communication (Howick et al., 2018), the therapeutic relationship (Bishop et al., 2021), and the promotion of salutogenic upstream behaviours (Wang et al., 2018; Williams, 2018) have small to moderate effects on patient health (Howick et al., 2018; Blease, 2022) and may have greater effects in combination (Sherriff et al., 2022). It remains to be studied how these insights play out in the COP context.

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) usually evaluate adverse events. In trials of COP, adverse effects commonly include transient post-treatment soreness and infrequent serious medical complications (Carnes et al., 2010; Hebert et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2013). Rarely do COP RCTs, however, study upstream mediators of negative health outcomes, such as increases in fear-avoidance behaviour, negative health beliefs, and effects on pain coping mechanisms. In doing so, especially in real-world settings and monitoring such effects long-term, RCTs could provide important information to whether COP are indeed associated with nocebo and other undesirable effects (Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2021a). Quantitative and qualitative assessments of potential changes in healthcare utilisation may be additional indicators of whether COP promoted active versus passive coping.

The third step: Implementation

The implementation of beneficial change must be based on educational media campaigns that change how we perceive musculoskeletal pain at a societal level (Gross et al., 2012; Hodges et al., 2021). Change is certainly driven most effectively by reforming institutional curricula and targeted professional training at practitioner level. However, clinical guidelines and incentive structures need to become better at curbing unnecessary use while allowing for evidence-based long-term care where needed (Buchbinder et al., 2020). Once reformed and having filled with life a new evidence-based whole-person model of care, practitioners and educational institutions are in a better position to take leading roles in highlighting the role of organisations and healthcare systems as well as systemic socio-economic determinants of ill-health or poor outcomes, and advocating for the people most affected (Nunan et al., 2021).

Conclusion

This article focused on an inherently negative phenomenon. Whilst this may have been challenging to read at times, we would like to finish on a positive note: By actively screening theory and practice for potential sources of nocebo, new avenues open to understand and enhance the positive potential routinely observed in clinicians’ care of individuals with musculoskeletal pain. Such reflection allows us to draw on a contemporary framing of manual and physical approaches and integrate them with psychologically-informed best-practice (Keefe et al., 2018).

Seeing this as a maturing and learning process, the question is not whether COP interventions are better than sham treatments for certain conditions, but rather how we can optimise and individualise these complex interventions to maximise the benefit for suffering individuals and for society.

Overall, many contemporary treatment approaches for pain can be interpreted as the attempt to reduce nocebo effects by creating positive expectations, unlearning of pain conditioning, and addressing psychosocial predictors of long-term pain. In addition to the honest and careful examination of their treatments for the inadvertent creation of nocebo effects, COP clinicians should increasingly incorporate such a rationale into their treatments to enhance the salutogenic potential of COP care for the benefit of their patients.

Declaration of competing interest

DHS works at several osteopathic education institutions and has received consultancy fees from Altern Health Ltd., an enterprise developing digital therapeutics for pain management. OT receives fees for delivering courses on low back pain communication and podcasting. GR leads education programmes on placebo, nocebo effects, and contextual factors in healthcare to under- and postgraduate students along with private CPD courses. MM has received travel expenses and/or honoraria as an invited speaker regarding therapeutic relationship from San Diego Pain Summit, Physio Austria, and Münster University of Applied Sciences. DN has no conflicts of interests to declare in relation to this work. LR receives fees for delivering communication courses and is currently working on a research project funded by Pfizer. LV has received consulting fees from Lundbeck. JDR receives fees for delivering pain management courses.

References:

Alvarez Bustins et al., 2018

G. Alvarez Bustins, P.-V. López Plaza, S.R. Carvajal

Profile of osteopathic practice in Spain:

results from a standardized data collection study

BMC Compl. Alternative Med. (2018)Alvarez et al., 2021

G. Alvarez, R. Zegarra-Parodi, J.E. Esteves

Person-centered versus body-centered approaches in

osteopathic care for chronic pain conditions

Therap. Adv. Musculoskeletal, 13 (2021),

10.1177/1759720X211029417 1759720X211029417Amanzio et al., 2009

M. Amanzio, L.L. Corazzini, L. Vase, F. Benedetti

A systematic review of adverse events in placebo groups

of anti-migraine clinical trials

Pain, 146 (2009), pp. 261-269, 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.010Anhang Price et al., 2014

R. Anhang Price, M.N. Elliott, A.M. Zaslavsky, R.D. Hays, W.G. Lehrman, et al

Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality

Med. Care Res. Rev., 71 (2014), pp. 522-554,

10.1177/1077558714541480Arandia and Di Paolo, 2021

I.R. Arandia, E.A. Di Paolo

Placebo from an enactive perspective

Front. Psychol., 12 (2021), 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660118Ashar et al., 2021

Y.K. Ashar, A. Gordon, H. Schubiner, C. Uipi, K. Knight, Z. Anderson, J. Carlisle, L. et al

Effect of pain reprocessing therapy vs placebo and usual care

for patients with chronic back pain: a randomized clinical trial

JAMA Psychiatr. (2021), 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2669Axén et al., 2019

I. Axén, L. Hestbaek, C. Leboeuf-Yde

Chiropractic Maintenance Care - What’s New?

A Systematic Review of the Literature

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2019 (Nov 21); 27: 63Beliveau et al., 2017

Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, Simon NB, Bussieres AE, Mior SA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35Benedetti et al., 2022

F. Benedetti, E. Frisaldi, A. Shaibani

Thirty years of neuroscientific investigation of placebo and nocebo:

the interesting, the good, and the bad

Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 62 (2022), pp. 323-340, 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-052120-104536Benedetti and Piedimonte, 2019

F. Benedetti, A. Piedimonte

The neurobiological underpinnings of placebo and nocebo effects.

Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism,

Advances in Targeted Therapies Proceed. 2019 Meeting,

49 (2019), p. S18, 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.09.015 –S21Benedetti et al., 2018

F. Benedetti, A. Piedimonte, E. Frisaldi

How do placebos work?

Eur. J. Psychotraumatol., 9 (2018), Article 1533370, 10.1080/20008198.2018.1533370Berna et al., 2017

C. Berna, I. Kirsch, S.R. Zion, Y.C. Lee, K.B. Jensen, P. Sadler, T.J. Kaptchuk, R.R. Edwards

Side effects can enhance treatment response through expectancy effects:

an experimental analgesic randomized controlled trial

Pain, 158 (2017), pp. 1014-1020, 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000870Bialosky et al., 2017

J.E. Bialosky, M.D. Bishop, C.W. Penza

Placebo mechanisms of manual therapy: a sheep in wolf ’s clothing?

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 47 (2017), pp. 301-304, 10.2519/jospt.2017.0604Bialosky et al., 2009

J.E. Bialosky, M.D. Bishop, D.D. Price, M.E. Robinson, S.Z. George

The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment

of musculoskeletal pain: a comprehensive model

Man. Ther., 14 (2009), pp. 531-538, 10.1016/j.math.2008.09.001Bingel et al., 2022

U. Bingel, K. Wiech, C. Ritter, V. Wanigasekera, R. Ní Mhuircheartaigh, M.C.

Hippocampus mediates nocebo impairment of opioid analgesia

through changes in functional connectivity

Eur. J. Neurosci., 56 (2022), pp. 3967-3978, 10.1111/ejn.15687Bishop et al., 2021

F. Bishop, M. Al-Abbadey, L. Roberts, H. MacPherson, B. Stuart, D. Carnes, C. Fawkes, L. Yardley,

Direct and mediated effects of treatment context on

low back pain outcome: a prospective cohort study

BMJ Open, 11 (2021), Article e044831, 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044831Bishop et al., 2017

F.L. Bishop, B. Coghlan, A.W. Geraghty, H. Everitt, P. Little, M.M. Holmes, D. Seretis, G. Lewith

What techniques might be used to harness placebo effects in non-malignant pain?

A literature review and survey to develop a taxonomy

BMJ Open, 7 (2017), Article e015516, 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015516Blease, 2022

C. Blease

Sharing online clinical notes with patients: implications

for nocebo effects and health equity

J. Med. Ethics (2022), 10.1136/jme-2022-108413Blokzijl et al., 2021

J. Blokzijl, R.H. Dodd, T. Copp, S. Sharma, E. Tcharkhedian, C. Klinner, C.G. Maher, A.C. Traeger

Understanding overuse of diagnostic imaging for patients with

low back pain in the Emergency Department:

a qualitative study

Emerg. Med. J., 38 (2021), pp. 529-536, 10.1136/emermed-2020-210345Bosman et al., 2021

M. Bosman, S. Elsenbruch, M. Corsetti, J. Tack, M. Simrén, B. Winkens, T. Boumans, A. Masclee

The placebo response rate in pharmacological trials in patients

with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (2021), 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00023-6Brummelman et al., 2019

E. Brummelman, D. Terburg, M. Smit, S.M. Bögels, P.A. Bos

Parental touch reduces social vigilance in children

Dev. Cognit. Neurosci. Social Touch.:

A new vista for developmental cognitive neuroscience?,

35 (2019), pp. 87-93, 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.05.002Buchbinder R, Underwood M, Hartvigsen J, Maher CG (2020)

The Lancet Series Call to Action to Reduce Low Value Care

for Low Back Pain: An Update

Pain. 2020 (Sep); 161 (1): S57–S64Burke et al., 2013

S.R. Burke, R. Myers, A.L. Zhang

A profile of osteopathic practice in Australia 2010–2011:

a cross sectional survey

BMC Muscoskel. Disord., 14 (2013), p. 227,

10.1186/1471-2474-14-227Carnes et al., 2017

D. Carnes, T. Mars, A. Plunkett, L. Nanke, H. Abbey

A mixed methods evaluation of a third wave cognitive behavioural therapy

and osteopathic treatment programme for chronic pain in primary care (OsteoMAP)

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 24 (2017), pp. 12-17,

10.1016/j.ijosm.2017.03.005Carnes et al., 2010

D. Carnes, T.S. Mars, B. Mullinger, R. Froud, M. Underwood

Adverse events and manual therapy: a systematic review

Man. Ther., 15 (2010), pp. 355-363, 10.1016/j.math.2009.12.006Carter, 2000

R. Carter

Subluxation - the silent killer

J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc., 44 (2000), pp. 9-18Cashin et al., 2021

A.G. Cashin, J.H. McAuley, S.E. Lamb, H. Lee

Disentangling contextual effects from musculoskeletal treatments

Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 29 (2021), pp. 297-299,

10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.011Chaibi et al., 2017

A. Chaibi, H. Knackstedt, P.J. Tuchin, M.B. Russell

Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Cervicogenic Headache:

A Single-blinded, Placebo, Randomized Controlled Trial

BMC Res Notes. 2017 (Jul 24); 10 (1): 310Chen et al., 2019

Q. Chen, E.W. Beal, V. Okunrintemi, E. Cerier, A. Paredes, S. Sun, G. Olsen, T.M. Pawlik

The association between patient satisfaction and patient-reported health outcomes

J. Patient. Exp., 6 (2019), pp. 201-209, 10.1177/2374373518795414Chiropractic, 2017

Chiropractic [WWW Document]

nhs.UK 8.24.22

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/chiropractic/ (2017)Coleshill et al., 2021

M.J. Coleshill, L. Sharpe, B. Colagiuri

No evidence that attentional bias towards pain-related words is associated

with verbally induced nocebo hyperalgesia: a dot-probe study

Pain Rep, 6 (2021), 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000921Colloca and Barsky, 2020

L. Colloca, A.J. Barsky

Placebo and nocebo effects

N. Engl. J. Med., 382 (2020), pp. 554-561, 10.1056/NEJMra1907805Cowell et al., 2018

I. Cowell, P. O'Sullivan, K. O'Sullivan, R. Poyton, A. McGregor, G. Murtagh

Perceptions of physiotherapists towards the management of non-specific

chronic low back pain from a biopsychosocial perspective: a qualitative study

Muscoskel. Sci. Pract., 38 (2018), pp. 113-119, 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.10.006Daniali and Flaten, 2019

H. Daniali, M.A. Flaten

A qualitative systematic review of effects of provider characteristics

and nonverbal behavior on pain, and placebo and nocebo effects

Front. Psychiatr., 10 (2019)Demertzi et al., 2009

A. Demertzi, C. Liew, D. Ledoux, M.-A. Bruno, M. Sharpe, S. Laureys, A. Zeman

Dualism persists in the science of mind

Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 1157 (2009), pp. 1-9, 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.04117.xDougherty et al., 2014

P.E. Dougherty, J. Karuza, A.S. Dunn, D. Savino, P. Katz

Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Chronic Lower Back Pain in

Older Veterans: A Prospective, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehab. 2014 (Dec); 5 (4): 154–164Draper-Rodi et al., 2018

J. Draper-Rodi, S. Vogel, A. Bishop

Identification of prognostic factors and assessment methods on the

evaluation of non-specific low back pain in a biopsychosocial environment: a scoping review

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 30 (2018), pp. 25-34, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2018.07.001Eklund, A., I. Jensen, M. Lohela-Karlsson, J. Hagberg, C. Leboeuf-Yde, et al. (2018).

The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Effectiveness of Chiropractic

Maintenance Care Versus Symptom-guided Treatment for Recurrent and

Persistent Low Back Pain - A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial

PLoS One. 2018 (Sep 12); 13 (9): e0203029Ekman et al., 2011

I. Ekman, K. Swedberg, C. Taft, A. Lindseth, A. Norberg, E. Brink, J. Carlsson, S.

Person-Centered care — ready for prime time

Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs., 10 (2011), pp. 248-251, 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008Engel, 1981

G.L. Engel

The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model

J. Med. Philos.: Forum. Bioeth. Philos. Med., 6 (1981), pp. 101-124, 10.1093/jmp/6.2.101Esteves et al., 2020

J.E. Esteves, R. Zegarra-Parodi, P. van Dun, F. Cerritelli, P. Vaucher

Models and theoretical frameworks for osteopathic care –

a critical view and call for updates and research

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 35 (2020), pp. 1-4, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2020.01.003Evers et al., 2018

A.W.M. Evers, L. Colloca, C. Blease, M. Annoni, L.Y. Atlas, F. Benedetti, U.

Implications of placebo and nocebo effects for clinical practice: expert consensus

PPS, 87 (2018), pp. 204-210, 10.1159/000490354Evers et al., 2021

A.W.M. Evers, L. Colloca, C. Blease, J. Gaab, K.B. Jensen, L.Y. Atlas, C.J.

What should clinicians tell patients about placebo and nocebo effects?

Practical considerations based on expert consensus

PPS, 90 (2021), pp. 49-56, 10.1159/000510738Farmer et al., 2021

C. Farmer, D.A. O'Connor, H. Lee, K. McCaffery, C. Maher, D. Newell, A. Cashin, D

Consumer understanding of terms used in imaging reports

requested for low back pain: a cross-sectional survey

BMJ Open, 11 (2021), Article e049938, 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049938Fawkes and Carnes, 2021

C. Fawkes, D. Carnes

Patient reported outcomes in a large cohort of patients

receiving osteopathic care in the United Kingdom

PLoS One, 16 (2021), Article e0249719, 10.1371/journal.pone.0249719Fawkes et al., 2014

C.A. Fawkes, C.M.J. Leach, S. Mathias, A.P. Moore

A profile of osteopathic care in private practices in the United Kingdom:

a national pilot using standardised data collection

Man. Ther., 19 (2014), pp. 125-130, 10.1016/j.math.2013.09.001Fenton et al., 2012

J.J. Fenton, A.F. Jerant, K.D. Bertakis, P. Franks

The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction,

health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality

Arch. Intern. Med., 172 (2012), pp. 405-411, 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662Field and Newell, 2016

J.R. Field, D. Newell

Clinical outcomes in a large cohort of musculoskeletal patients undergoing

chiropractic care in the United Kingdom: a comparison of self-

and national health service–referred routes

J. Manipulative Physiol. Therapeut., 39 (2016), pp. 54-62, 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.12.003Fryer, 2016

G. Fryer

Somatic dysfunction: an osteopathic conundrum

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 22 (2016), pp. 52-63, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2016.02.002Gelso and Kline, 2019

C.J. Gelso, K.V. Kline

The sister concepts of the working alliance and the real relationship:

on their development, rupture, and repair

Res Psychother, 22 (2019), p. 373, 10.4081/ripppo.2019.373Gershgoren et al., 2011

L. Gershgoren, G. Tenenbaum, A. Gershgoren, R.C. Eklund

The effect of parental feedback on young athletes' perceived motivational

climate, goal involvement, goal orientation, and performance

Psychol. Sport Exerc., 12 (2011), pp. 481-489, 10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.05.003Gibson et al., 2020

B.E. Gibson, G. Terry, J. Setchell, F.A.S. Bright, C. Cummins, N.M. Kayes

The micro-politics of caring: tinkering with person-centered rehabilitation

Disabil. Rehabil., 42 (2020), pp. 1529-1538, 10.1080/09638288.2019.1587793Gíslason et al., 2019

H.F. Gíslason, J.K. Salminen, L. Sandhaugen, A.S. Storbråten, R. Versloot, I. Roug, D. Newell

The shape of chiropractic in Europe:

a cross sectional survey of chiropractor's beliefs and practice

Chiropr. Man. Ther., 27 (2019), p. 16, 10.1186/s12998-019-0237-zGliedt et al., 2020

J.A. Gliedt, P.J. Battaglia, B.D. Holmes The prevalence of psychosocial related terminology in chiropractic

program courses, chiropractic accreditation standards, and chiropractic

examining board testing content in the United States

Chiropr. Man. Ther., 28 (2020), p. 43, 10.1186/s12998-020-00332-7Godfrey, 2020

N. Godfrey

An Exploration of the Relationship between Pilates Teachers

and Clients with Persistent Low Back Painv (2020)Gray,

Gray Institute - blog

[WWW Document], n.d. URL, 7.3.21

https://grayinstitute.com/blogGreville-Harris and Dieppe, 2015

M. Greville-Harris, P. Dieppe

Bad is more powerful than good: the nocebo response in medical consultations

Am. J. Med., 128 (2015), pp. 126-129, 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.08.031Gross et al., 2012

D.P. Gross, S. Deshpande, E.L. Werner, M.F. Reneman, M.A. Miciak, R. Buchbinder

Fostering change in back pain beliefs and behaviors:

when public education is not enough

Spine J., 12 (2012), pp. 979-988, 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.09.001Hebert et al., 2015

Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, French SD, et al.

Serious Adverse Events and Spinal Manipulative Therapy

of the Low Back Region: A Systematic Review of Cases

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 677–691Herman et al., 2018

P.M. Herman, M. Kommareddi, M.E. Sorbero, C.M. Rutter, R.D. Hays, L.G. Hilton

Characteristics of chiropractic patients being treated

for chronic low back and neck pain

J. Manipulative Physiol. Therapeut., 41 (2018), pp. 445-455, 10.1016/j.jmpt.2018.02.001Hodges et al., 2021

P.W. Hodges, L. Hall, J. Setchell, S. French, J. Kasza, K. Bennell, D. Hunter, B.

Effect of a consumer-focused website for low back pain on health literacy,

treatment choices, and clinical outcomes: randomized controlled trial

J. Med. Internet Res., 23 (2021), Article e27860, 10.2196/27860Hofmann, 2016

B. Hofmann

Medicalization and overdiagnosis: different but alike

Med Health Care. Philos., 19 (2016), pp. 253-264, 10.1007/s11019-016-9693-6Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2022a

D. Hohenschurz-Schmidt, et al

Blinding and sham control methods in trials of physical, psychological,

and self-management interventions for pain (article I):

a systematic review and description of methods

PAIN 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002723 https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002723 (2022)Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2022b D. Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al

Blinding and sham control methods in trials of physical, psychological,

and self-management interventions for pain (article II):

a meta-analysis relating methods to trial results

PAIN 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002730 https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002730 (2022)Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2021a

D. Hohenschurz-Schmidt, B.A. Kleykamp, J. Draper-Rodi, J. Vollert, J. Chan, et al

Pragmatic trials of pain therapies:

a systematic review of methods

PAIN https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002317 (2021)Hohenschurz-Schmidt et al., 2021b

D. Hohenschurz-Schmidt, J. Vollert, S. Vogel, A.S.C. Rice, J. Draper-Rodi

Performing and interpreting randomized clinical trials

J. Osteopath. Med. (2021), 10.1515/jom-2020-0320Hornung et al., 2022

A.L. Hornung, S.S. Rudisill, R.W. Suleiman, Z.K. Siyaji, S. Sood, S. Siddiqui,

Low back pain: what is the role of YouTube content in patient education?

J. Orthop. Res., 40 (2022), pp. 901-908, 10.1002/jor.25104Howick et al., 2018

J. Howick, A. Moscrop, A. et al

Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations:

a systematic review and meta-analysis

J. R. Soc. Med., 111 (2018), pp. 240-252, 10.1177/0141076818769477Hutchinson and Moerman, 2018

P. Hutchinson, D.E. Moerman

The meaning response, “placebo,” and methods

Perspect. Biol. Med., 61 (2018), pp. 361-378, 10.1353/pbm.2018.0049Hüter-Becker, 2004

A. Hüter-Becker

Geschichte der Physiotherapie. A. Hüter-Becker & M. Dölken.

Beruf, Recht, wissenschaftliches Arbeiten.

Stuttgart: Thieme (2004)Hutting et al., 2022

N. Hutting, J.P. Caneiro, O.M. Ong’wen, M. Miciak, L. Roberts

Patient-centered care in musculoskeletal practice:

key elements to support clinicians to focus on the person

Muscoskel. Sci. Pract., 57 (2022), Article 102434, 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102434Jenkins et al., 2016

H.j. Jenkins, M.j. Hancock, C.g. Maher, S.d. French, J.s. Magnussen

Understanding patient beliefs regarding the use of

imaging in the management of low back pain

Eur. J. Pain, 20 (2016), pp. 573-580, 10.1002/ejp.764Jenkins et al., 2018a

H.J. Jenkins, A.S. Downie, C.G. Maher, N.A. Moloney, J.S. Magnussen, M.J. Hancock

Imaging for low back pain: is clinical use consistent

with guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis

Spine J., 18 (2018), pp. 2266-2277, 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.05.004Jenkins et al., 2018b H.J. Jenkins, A.S. Downie, C.S. Moore, S.D. French

Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession:

a narrative review

Chiropr. Man. Ther., 26 (2018), p. 48, 10.1186/s12998-018-0217-8JIPS,

JIPS

Journal of interdisciplinary placebo studies DATABASE n.d. URL, 8.25.22

https://jips.online/Jonas, 2018

W. Jonas

How Healing Works: Get Well and Stay Well Using Your Hidden Power to Heal

(Illustrated edition), Lorena Jones Books, California (2018)Kaptchuk, 2011

T.J. Kaptchuk

Placebo studies and ritual theory: a comparative analysis

of Navajo, acupuncture and biomedical healing

Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci., 366 (2011), pp. 1849-1858, 10.1098/rstb.2010.0385Keefe et al., 2018

F.J. Keefe, C.J. Main, S.Z. George

Advancing psychologically informed practice for patients with

persistent musculoskeletal pain: promise, pitfalls, and solutions

Phys. Ther., 98 (2018), pp. 398-407, 10.1093/ptj/pzy024Kendrick et al., 2001

D. Kendrick, K. Fielding, E. Bentley, R. Kerslake, P. Miller, M. Pringle

Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients

with low back pain: randomised controlled trial

BMJ, 322 (2001), pp. 400-405, 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.400Kharel et al., 2021

P. Kharel, J.R. Zadro, C.G. Maher

Physiotherapists can reduce overuse by Choosing Wisely

J. Physiother. (2021), 10.1016/j.jphys.2021.06.006Kim et al., 2022

J. Kim, J.E. Esteves, F. Cerritelli, K. Friston

An active inference account of touch and verbal communication in therapy

Front. Psychol., 13 (2022), Article 828952, 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828952Kleine-Borgmann and Bingel, 2018

J. Kleine-Borgmann, U. Bingel

Chapter fifteen - nocebo effects: neurobiological mechanisms

and strategies for prevention and optimizing treatment

L. Colloca (Ed.), International Review of Neurobiology,

Neurobiology of the Placebo Effect Part I,

Academic Press (2018), pp. 271-283, 10.1016/bs.irn.2018.02.005Korakakis et al., 2019

V. Korakakis, K. O'Sullivan, P.B. O'Sullivan, V. Evagelinou, Y. Sotiralis, A. Sideris, K.et al

Physiotherapist perceptions of optimal sitting and standing posture

Musculoskelet Sci Pract, 39 (2019), pp. 24-31, 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.11.004Kriznik et al., 2018

N.M. Kriznik, A.L. Kinmonth, T. Ling, M.P. Kelly

Moving beyond individual choice in policies to reduce health inequalities:

the integration of dynamic with individual explanations

J. Publ. Health, 40 (2018), pp. 764-775, 10.1093/pubmed/fdy045Langridge et al., 2016

N. Langridge, L. Roberts, C. Pope

The role of clinician emotion in clinical reasoning: balancing the analytical process

Man. Ther., 21 (2016), pp. 277-281, 10.1016/j.math.2015.06.007Leboeuf-Yde et al., 1997

C. Leboeuf-Yde, B. Hennius, E. Rudberg, P. Leufvenmark, M. Thunman

Side effects of chiropractic treatment: a prospective study

J. Manip. Physiol. Ther., 20 (1997), pp. 511-515Lederman, 2017

E. Lederman

A process approach in osteopathy: beyond the structural model

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 23 (2017), pp. 22-35, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2016.03.004Lederman, 2011

E. Lederman

The fall of the postural-structural-biomechanical model in

manual and physical therapies: exemplified by lower back pain

J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther., 15 (2011), pp. 131-138, 10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.01.011Lemmers et al., 2019

G.P.G. Lemmers, W. van Lankveld, G.P. Westert, P.J. van der Wees, J.B. Staal

Imaging versus no imaging for low back pain: a systematic review,

measuring costs, healthcare utilization and absence from work

Eur. Spine J., 28 (2019), pp. 937-950, 10.1007/s00586-019-05918-1Leventhal et al., 2016

H. Leventhal, L.A. Phillips, E. Burns

The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM):

a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management

J. Behav. Med., 39 (2016), pp. 935-946, 10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2Liem, 2016

T. Liem

A.T. Still's osteopathic lesion theory and evidence-based models

supporting the emerged concept of somatic dysfunction

J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc., 116 (2016), pp. 654-661, 10.7556/jaoa.2016.129Liem, 2009

T. Liem

Cranial Osteopathy: a Practical Textbook

Eastland Press, Seattle, WA (2009)Linker, 2021

B. Linker

Toward a History of Ableness. All of Us (2021)

URL, 7.3.21

https://allofusdha.org/research/toward-a-history-of-ableness/Linker, 2005

B. Linker

Strength and science: gender, physiotherapy, and medicine in the United States, 1918-35

J. Wom. Hist., 17 (2005), pp. 106-132, 10.1353/jowh.2005.0034Locher et al., 2019 C.

Locher, H. Koechlin, J. Gaab, H. Gerger

The other side of the coin: nocebo effects and psychotherapy

Front. Psychiatr., 10 (2019), 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00555Macdonald et al., 2018

M. Macdonald, P. Vaucher, J.E. Esteves

The beliefs and attitudes of UK registered osteopaths towards chronic

pain and the management of chronic pain sufferers -

a cross-sectional questionnaire based survey

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 30 (2018), pp. 3-11, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2018.07.003MacMillan, 2021

A. MacMillan Osteopathic ableism: a critical disability view

of traditional osteopathic theory in modern practice

Int. J. Osteopath. Med. (2021), 10.1016/j.ijosm.2021.12.005Maia et al., 2021

L.B. Maia, J.P. Silva, M.B. Souza, N. Henschke, V.C. Oliveira

Popular videos related to low back pain on YouTubeTM do not reflect

current clinical guidelines: a cross-sectional study

Braz. J. Phys. Ther., 25 (2021), pp. 803-810, 10.1016/j.bjpt.2021.06.009Manaï et al., 2019

M. Manaï, H. van Middendorp, D.S. Veldhuijzen, T.W.J. Huizinga, A.W.M. Evers

How to prevent, minimize, or extinguish nocebo effects in pain:

a narrative review on mechanisms, predictors, and interventions

Pain. Rep., 4 (2019), p. e699, 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000699Marcon et al., 2019

A.R. Marcon, B. Murdoch, T. Caulfield

The “subluxation” issue: an analysis of chiropractic clinic websites

Arch. Physiother., 9 (2019), p. 11, 10.1186/s40945-019-0064-5Marcum, 2005

J.A. Marcum

Biomechanical and phenomenological models of the body,

the meaning of illness and quality of care

Med Health Care Philos, 7 (2005), pp. 311-320, 10.1007/s11019-004-9033-0Marmot, 2020

M. Marmot

Health equity in england: the Marmot review 10 years on

BMJ, 368 (2020), 10.1136/bmj.m693May et al., 2004

C. May, G. Allison, A. Chapple, C. Chew-Graham, C. Dixon, L. Gask, R. Graham, A.

Framing the doctor-patient relationship in chronic illness:

a comparative study of general practitioners' accounts

Sociol. Health Illness, 26 (2004), pp. 135-158, 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00384.xMcCabe et al., 2021

E. McCabe, M. Miciak, M. Roduta Roberts, H. Sun, Linda), D.P. Gross

Measuring therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: conceptual foundations

Physiother. Theory Pract. (2021), pp. 1-13, 10.1080/09593985.2021.1987604McGill et al., 2015

R. McGill, E. Anwar, L. Orton, H. Bromley, F. Lloyd-Williams,

Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective

for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact

BMC Publ. Health, 15 (2015), p. 457, 10.1186/s12889-015-1781-7McMurtry et al., 2006

C.M. McMurtry, P.J. McGrath, C.T. Chambers

Reassurance can hurt: parental behavior and painful medical procedures

J. Pediatr., 148 (2006), pp. 560-561, 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.040McRae and Hancock, 2017

M. McRae, M.J. Hancock

Adults attending private physiotherapy practices seek diagnosis, pain relief,

improved function, education and prevention: a survey

J. Physiother., 63 (2017), pp. 250-256, 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.08.002McRuer, 2010

R. McRuer

Compulsory able-bodiedness and queer/disabled existence

Disabil. Stud. Read., 3 (2010), pp. 383-392Meyer et al., 2017

A.-L. Meyer, A. Meyer, S. Etherington, C. Leboeuf-Yde

Unravelling Functional Neurology: A Scoping Review of Theories and

Clinical Applications in a Context of Chiropractic Manual Therapy

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Jul 18); 25: 19Miciak et al., 2019

M. Miciak, M. Mayan, C. Brown, A.S. Joyce, D.P. Gross

A framework for establishing connections in physiotherapy practice

Physiother. Theory Pract., 35 (2019), pp. 40-56, 10.1080/09593985.2018.1434707Miciak et al., 2018

M. Miciak, M. Mayan, C. Brown, A.S. Joyce, D.P. Gross

The necessary conditions of engagement for the therapeutic relationship

in physiotherapy: an interpretive description study

Arch Physiother, 8 (2018), p. 3, 10.1186/s40945-018-0044-1Miciak and Rossettini, 2022

M. Miciak, G. Rossettini

Looking at both sides of the coin: addressing rupture of the

therapeutic relationship in musculoskeletal physical therapy/physiotherapy

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 52 (2022), pp. 500-504, 10.2519/jospt.2022.11152Mior S, Wong J, Sutton D, Beliveau PJ, Bussières A, Hogg-Johnson S, French S.

Understanding patient profiles and characteristics of current chiropractic practice:

a cross-sectional Ontario Chiropractic Observation and Analysis STudy (O-COAST)

BMJ Open 2019 (Aug 26); 9 (8): e029851Morris et al., 2013

B.J. Morris, A.A. Jahangir, M.K. Sethi

Patient satisfaction: an emerging health policy issue:

what the orthopaedic surgeon needs to know

AAOS Now (2013), pp. 29-30Moseley and Butler, 2015

G.L. Moseley, D.S. Butler

Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future

J. Pain, 16 (2015), pp. 807-813, 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.005Moynihan et al., 2012

R. Moynihan, J. Doust, D. Henry

Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy

BMJ, 344 (2012), Article e3502, 10.1136/bmj.e3502Myers, 2012

T. Myers

Anatomy trains and force transmission

R. Schleip, T.W. Findley, L. Chaitow, P.A. Huijing (Eds.),

Fascia: the Tensional Network of the Human Body,

Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, London (2012), pp. 131-136Naderi et al., 2007

S. Naderi, N. Andalkar, E.C. Benzel

History of spine biomechanics: part II—from the renaissance to the 20TH century

Neurosurgery, 60 (2007), pp. 392-404, 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249263.80579.F9Newell et al., 2017

D. Newell, L.R. Lothe, T.J.L. Raven

Contextually Aided Recovery (CARe): a scientific theory for innate healing

Chiropr. Man. Ther., 25 (2017), p. 6, 10.1186/s12998-017-0137-zNg et al., 2021

W. Ng, H. Slater, C. Starcevich, A. Wright, T. Mitchell, D. Beales

Barriers and enablers influencing healthcare professionals' adoption of a

biopsychosocial approach to musculoskeletal pain:

a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis

Pain, 162 (2021), pp. 2154-2185, 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002217Nicholls, 2017

D.A. Nicholls

The End of Physiotherapy

Routledge, London (2017), 10.4324/9781315561868Nicholls and Gibson, 2010

D.A. Nicholls, B.E. Gibson

The body and physiotherapy

Physiother. Theory Pract., 26 (2010), pp. 497-509, 10.3109/09593981003710316Nijs et al., 2013

J. Nijs, N. Roussel, C. Paul van Wilgen, A. Köke, R. Smeets

Thinking beyond muscles and joints: therapists' and patients' attitudes

and beliefs regarding chronic musculoskeletal pain are key to applying effective treatment

Man. Ther., 18 (2013), pp. 96-102, 10.1016/j.math.2012.11.001Nunan et al., 2021

D. Nunan, D.N. Blane, M. McCartney

Exemplary medical care or Trojan horse?

An analysis of the ‘lifestyle medicine’ movement

Br. J. Gen. Pract., 71 (2021), pp. 229-232O'Keeffe et al., 2016

M. O'Keeffe, P. Cullinane, J. Hurley, I. Leahy, S. Bunzli, P.B. O'Sullivan, K. O'Sullivan

What influences patient-therapist interactions in

musculoskeletal physical therapy?

Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis

Phys. Ther., 96 (2016), pp. 609-622, 10.2522/ptj.20150240O'Keeffe et al., 2022

M. O'Keeffe, G.E. Ferreira, I.A. Harris, B. Darlow, R. Buchbinder, A.C. Traeger, et al

Effect of diagnostic labelling on management intentions for non-specific

low back pain: a randomized scenario-based experiment

Eur. J. Pain, 26 (2022), pp. 1532-1545, 10.1002/ejp.1981Oostendorp et al., 2015

R.A.B. Oostendorp, H. Elvers, E. Miko?ajewska, M. Laekeman, E. van Trijffel, H. Samwel, W. Duquet

Manual physical therapists' use of biopsychosocial history taking

in the management of patients with back or neck pain in clinical practice

Sci. World J., 2015 (2015), Article e170463, 10.1155/2015/170463Osborn-Jenkins and Roberts, 2021

L. Osborn-Jenkins, L. Roberts

The advice given by physiotherapists to people with back pain in primary care

Muscoskel. Sci. Pract., 55 (2021), Article 102403, 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102403Osteopathy, 2017

Osteopathy [WWW Document] nhs.UK 8.24.22

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteopathy/ (2017)O'Sullivan et al., 2012

K. O'Sullivan, P. O'Sullivan, L. O'Sullivan, W. Dankaerts

What do physiotherapists consider to be the best sitting spinal posture?

Man. Ther., 17 (2012), pp. 432-437, 10.1016/j.math.2012.04.007O'Sullivan et al., 2018

P.B. O'Sullivan, J.P. Caneiro, M. O'Keeffe, A. Smith, W. Dankaerts, K. Fersum, K. O'Sullivan

Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach

for the targeted management of disabling low back pain

Phys. Ther., 98 (2018), pp. 408-423, 10.1093/ptj/pzy022Otto and Keller, 2014

H. Otto, H. Keller

Different Faces of Attachment: Cultural Variations on a Universal Human Need

Cambridge University Press (2014)Paulus, 2013

S. Paulus

The core principles of osteopathic philosophy

Int. J. Osteopath. Med. Spl. Issue: Osteopath.

Princ., 16 (2013), pp. 11-16, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2012.08.003Peschken and Johnson, 1997

W. Peschken, M. Johnson

Therapist and client trust in the therapeutic relationship

Psychother. Res., 7 (1997), pp. 439-447, 10.1080/10503309712331332133Petersen et al., 2014

G.L. Petersen, N.B. Finnerup, L. Colloca, M. Amanzio, D.D. Price, T.S. Jensen, L. Vase

The magnitude of nocebo effects in pain: a meta-analysis

PAIN®, 155 (2014), pp. 1426-1434, 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.016Petty et al., 2012

N.J. Petty, O.P. Thomson, G. Stew

Ready for a paradigm shift? Part 1: introducing the philosophy of qualitative research

Man. Ther., 17 (2012), pp. 267-274, 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.006Pincus et al., 2013

T. Pincus, N. Holt, S. Vogel, M. Underwood, R. Savage, D.A. Walsh, S.J.C. Taylor

Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes

in primary care: a systematic review

PAIN®, 154 (2013), pp. 2407-2416, 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.019Rajasekaran et al., 2021

S. Rajasekaran, S. Dilip Chand Raja, B.T. Pushpa, K.B. Ananda, S. Ajoy Prasad, M.K. Rishi

The catastrophization effects of an MRI report on the patient and surgeon

and the benefits of ‘clinical reporting’: results from an RCT and blinded trials

Eur. Spine J., 30 (2021), pp. 2069-2081, 10.1007/s00586-021-06809-0Roberts and Bucksey, 2007

L. Roberts, S.J. Bucksey

Communicating with patients: what happens in practice?

Phys. Ther., 87 (2007), pp. 586-594, 10.2522/ptj.20060077Roberts and Langridge, 2018

L. Roberts, N. Langridge

N.J. Petty, K. Barnard (Eds.),

Principles of Communication and its Application to Clinical Reasoning,

Elsevier (2018), pp. 209-233Rossettini et al., 2020a

G. Rossettini, E.M. Camerone, E. Carlino, F. Benedetti, M. Testa

Context Matters: The Psychoneurobiological Determinants

of Placebo, Nocebo and Context-related

Effects in Physiotherapy

Arch Physiother 2020 (Jun 11); 10: 11Rossettini et al., 2022

G. Rossettini, A. Colombi, E. Carlino, M. Manoni, M. Mirandola, A. Polli, E.M. Camerone

Unraveling negative expectations and nocebo-related effects in musculoskeletal pain

Front. Psychol., 13 (2022)Rossettini et al., 2020b

G. Rossettini, T.M. Latini, A. Palese, S.M. Jack, D. Ristori, S. Gonzatto, M. Testa

Determinants of patient satisfaction in outpatient musculoskeletal physiotherapy:

a systematic, qualitative meta-summary, and meta-synthesis

Disabil. Rehabil., 42 (2020), pp. 460-472, 10.1080/09638288.2018.1501102Rubinstein et al., 2019

S.M. Rubinstein, A. de Zoete, M. van Middelkoop, W.J.J. Assendelft, M.R. de Boer, M.W. van Tulder

Benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy for the treatment of

chronic low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

BMJ, 364 (2019), p. l689, 10.1136/bmj.l689Ryan et al., 1994

R.M. Ryan, J.D. Stiller, J.H. Lynch

Representations of relationships to teachers, parents, and friends

as predictors of academic motivation and self-esteem

J. Early Adolesc., 14 (1994), pp. 226-249, 10.1177/027243169401400207Safran and Kraus, 2014

J.D. Safran, J. Kraus

Alliance ruptures, impasses, and enactments: a relational perspective

Psychotherapy, 51 (2014), pp. 381-387, 10.1037/a0036815Sanan and Rengachary, 1996

A. Sanan, S.S. Rengachary

The history of spinal biomechanics

Neurosurgery, 39 (1996), pp. 657-668, 10.1097/00006123-199610000-00001Schemer et al., 2020

L. Schemer, W. Rief, J.A. Glombiewski

Treatment expectations towards different pain management approaches: two perspectives

J. Pain Res., 13 (2020), pp. 1725-1736, 10.2147/JPR.S247177Schiller, 2021

S. Schiller

The emergence of physiotherapy in Germany from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries:

a “female profession” concerned with movement in the health care arena

Physiother. Theory Pract., 37 (2021), pp. 359-375, 10.1080/09593985.2021.1887061Sergueef, 2007

N. Sergueef

Cranial Osteopathy for Infants, Children and Adolescents:

a Practical Handbook

Elsevier Health Sciences (2007)Shakespeare et al., 2017

T. Shakespeare, N. Watson, O.A. Alghaib

Blaming the victim, all over again:

waddell and Aylward's biopsychosocial (BPS) model of disability

Crit. Soc. Pol., 37 (2017), pp. 22-41, 10.1177/0261018316649120Sherriff et al., 2022

B. Sherriff, C. Clark, C. Killingback, D. Newell

Impact of contextual factors on patient outcomes following

conservative low back pain treatment: systematic review

Chiropr. Man. Ther., 30 (2022), p. 20, 10.1186/s12998-022-00430-8Simpson and Young, 2020

J.K. Simpson, K.J. Young

Vitalism in contemporary chiropractic: a help or a hindrance?

Chiropr. Man. Ther., 28 (2020), p. 35, 10.1186/s12998-020-00307-8Sorensen, 2006

A.T. Sorensen

Social learning and health plan choice

Rand J. Econ., 37 (2006), pp. 929-945, 10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00064.xStewart and Loftus, 2018

M. Stewart, S. Loftus

Sticks and stones: the impact of language in musculoskeletal rehabilitation

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 48 (2018), pp. 519-522, 10.2519/jospt.2018.0610Still, 1908

A.T. Still

Autobiography of Andrew T

Still. The author (1908)Stilwell and Harman, 2019

P. Stilwell, K. Harman

An enactive approach to pain: beyond the biopsychosocial model

Phenomenol. Cognitive Sci., 18 (2019), pp. 637-665, 10.1007/s11097-019-09624-7Synnott et al., 2015

A. Synnott, M. O'Keeffe, S. Bunzli, W. Dankaerts, P. O'Sullivan, K. O'Sullivan

Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people

with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery:

a systematic review

J. Physiother., 61 (2015), pp. 68-76, 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.02.016Testa and Rossettini, 2016

M. Testa, G. Rossettini

Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo:

how contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes

Man. Ther., 24 (2016), pp. 65-74, 10.1016/j.math.2016.04.006Thomson et al., 2021

O.P. Thomson, A. MacMillan, et al

Opposing vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic -

a critical commentary and united statement of an

international osteopathic research community

Int. J. Osteopath. Med., 39 (2021), pp. A1-A6, 10.1016/j.ijosm.2021.02.002Thomson et al., 2014

O.P. Thomson, N.J. Petty, A.P. Moore

A qualitative grounded theory study of the conceptions of clinical practice

in osteopathy – a continuum from technical rationality to professional artistry

Man. Ther., 19 (2014), pp. 37-43, 10.1016/j.math.2013.06.005Tinetti et al., 2016

M.E. Tinetti, A.D. Naik, J.A. Dodson

Moving from disease-centered to patient goals–directed care for patients

with multiple chronic conditions: patient value-based care

JAMA Cardiology, 1 (2016), pp. 9-10, 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0248Tozzi, 2012

P. Tozzi

Selected fascial aspects of osteopathic practice-

J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther., 16 (2012), pp. 503-519, 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.02.003Traeger et al., 2018

A.C. Traeger, H. Lee, M. Hübscher, et al

Effect of intensive patient education vs placebo patient education

on outcomes in patients with acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial

JAMA Neurol. (2018), 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3376Tsutsumi et al., 2022

Y. Tsutsumi, Y. Tsujimoto, et al

Proportion attributable to contextual effects in general medicine:

a meta-epidemiological study based on Cochrane reviews

BMJ Evid Based Med bmjebm-2021-111861 (2022), 10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111861Tuttle et al., 2015

A.H. Tuttle, S. Tohyama, T. Ramsay, J. Kimmelman, P. Schweinhardt, G.J. Bennett, J.S. Mogil

Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain

Pain, 156 (2015), p. 2616, 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000333Vollert et al., 2020

J. Vollert, N.R. Cook, T.J. Kaptchuk, S.T. Sehra, D.K. Tobias, K.T. Hall

Assessment of placebo response in objective and subjective

outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials

JAMA Netw. Open, 3 (2020), Article e2013196, 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13196Volz et al., 2021

M. Volz, S. Jennissen, H. Schauenburg, C. Nikendei, J.C. Ehrenthal, U. Dinger

Intraindividual dynamics between alliance and symptom severity

in long-term psychotherapy: why time matters

J. Counsel. Psychol., 68 (2021), pp. 446-456, 10.1037/cou0000545Walker et al., 2013

Walker, BF, Hebert, JJ, Stomski, NJ et al.

Outcomes of Usual Chiropractic.

The OUCH Randomized Controlled Trial of Adverse Events

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Sep 15); 38 (20): 1723–1729Wang et al., 2018

Y. Wang, C. Lombard, S.M. Hussain, C. Harrison, S. Kozica, S.R.E. Brady, H. Teede, F.M. Cicuttini

Effect of a low-intensity, self-management lifestyle intervention

on knee pain in community-based young to middle-aged rural women:

a cluster randomised controlled trial

Arthritis Res. Ther., 20 (2018), p. 74, 10.1186/s13075-018-1572-5Wartolowska et al., 2017

K.A. Wartolowska, S. Gerry, B.G. Feakins, G.S. Collins, J. Cook, A. Judge, A.J. Carr

A meta-analysis of temporal changes of response in the placebo arm

of surgical randomized controlled trials: an update

Trials, 18 (2017), p. 323, 10.1186/s13063-017-2070-9Williams, 2018

A.-//-W. Williams

Effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle intervention for

chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial

Pain, 159 (3043959) (2018), pp. 1137-1146, 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001198Zadro et al., 2020

J.R. Zadro, S. Décary, M. O'Keeffe, Z.A. Michaleff, A.C. Traeger

Overcoming overuse: improving musculoskeletal health care

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 50 (2020), pp. 113-115, 10.2519/jospt.2020.0102

Return to PLACEBOS

Since 11-12-2022

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |