Development and Validation of the EXPECT Questionnaire:

Assessing Patient Expectations of Outcomes of Complementary

and Alternative Medicine Treatments for Chronic PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Altern Complement Med. 2016 (Nov); 22 (11): 936–946 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Salene M. W. Jones, PhD, Jane Lange, PhD, Judith Turner, PhD, Dan Cherkin, PhD,

Cheryl Ritenbaugh, PhD, MPH, Clarissa Hsu, PhD, Heidi Berthoud, and Karen Sherman, PhD

Group Health Research Institute ,

Seattle, WA.BACKGROUND: Patient expectations may be associated with outcomes of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments for chronic pain. However, a psychometrically sound measure of such expectations is needed.

OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a questionnaire to assess individuals' expectations regarding outcomes of CAM treatments for chronic low back pain (CLBP), as well as a short form of the questionnaire.

METHODS: An 18-item draft questionnaire was developed through literature review, cognitive interviews with individuals with CLBP, CAM practitioners, and expert consultation.

Two samples completed the questionnaire:(1) a community sample (n = 141) completed it via an online survey before or soon after starting a CAM treatment for CLBP, and

(2) participants (n = 181) in randomized clinical trials evaluating CAM treatments for CLBP or fibromyalgia completed it prior to or shortly after starting treatment.Factor structure, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and criterion validity were examined.

RESULTS: Based on factor analyses, 10 items reflecting expectations (used to create a total score) and three items reflecting hopes (not scored) were selected for the questionnaire. The questionnaire had high internal consistency, moderate test-retest reliability, and moderate correlations with other measures of expectations. A three-item short form also had adequate reliability and validity.

CONCLUSIONS: The Expectations for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments (EXPECT) questionnaire can be used in research to assess individuals' expectations of treatments for chronic pain. It is recommended that the three hope questions are included (but not scored) to help respondents distinguish between hopes and expectations. The short form may be appropriate for clinical settings and when expectation measurement is not a primary focus.

KEYWORDS: acupuncture; back pain; chiropractic; complementary and alternative medicine; massage; yoga

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Greater knowledge about the effects of individuals’ expectations regarding outcomes from complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments for chronic pain is needed. Progress in this area has been hampered by the lack of valid and reliable measures, possibly explaining the inconsistent research. [1-6] Most measures of individuals’ expectations regarding CAM treatments were not developed systematically and were developed for one specific treatment. [7, 8] No questionnaires have been developed to assess individuals’ expectations across CAM therapies for chronic pain. Many studies used measures developed to assess treatment credibility. [7, 8] However, an individual's views regarding the credibility of a treatment may differ from their expectations about the likely effects of the treatment on their pain. Prior work also supports the importance of distinguishing expectations from other perceptions, such as credibility and hope. [9-11] Hopes reflect individuals’ views of the best-case scenario, whereas expectations are their appraisals of the most likely outcomes, and asking about hope may affect how respondents interpret questions about expectations. [9-11] To address these gaps in the literature, a measure of expectations for different CAM treatments for chronic low back pain (CLBP) was developed and evaluated. In recognition of the frequent need in research studies to minimize respondent burden, a short form of this questionnaire was also developed.

Methods

Questionnaire development: overview

The draft Expectations for CAM Treatments (EXPECT) questionnaire items were developed through an iterative process, including a review of the literature and interviews with individuals with CLBP and CAM practitioners. Questions were drafted to capture hopes and expectations for CAM treatment effects on three domains identified in previous work [9, 10] (pain relief, improved function, and improved mood and overall well-being). Questions were drafted about specific domains (sleep, mood) and how much change individuals hoped for and realistically expected in their back pain, and the impact of back pain on their life in one year. The draft questions were evaluated using cognitive interviews with individuals with CLBP [11] and were reviewed by seven CAM and pain experts. Using this input, the items were revised, and they were evaluated in additional cognitive interviews with individuals with CLBP.

The draft questionnaire included 18 items regarding individuals’ hopes and expectations about outcomes of CAM care for their pain. Each item had a 0–10 response scale, and some had an option for selecting “not applicable.” Anchors differed across items, but 0 always represented no change or worse and 10 represented maximal improvement (complete relief or no impact of back pain on the domain). All study procedures and materials were approved by the Group Health Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent.

Development of EXPECT questionnaire using community volunteersParticipants, setting, and procedures Between July 2013 and November 2014, individuals were recruited who were planning to begin or who had recently started acupuncture, chiropractic, massage, or yoga for CLBP. They were recruited from several sources, including practitioners, online advertisements, print advertisements, and panelists assembled by a survey research organization. Advertisements directed participants to the study Web site, which contained a description of the study and screening questions. Eligibility requirements included age between 20 and 70 years old; the ability to read English; Internet access; back pain for at least 3 months; back pain intensity in the previous week rated ≥3 on a 0–10 scale; plan to begin acupuncture, chiropractic, massage, or yoga for CLBP in the next month or started of one of those therapies in the past week; and no use of those therapies in the previous 3 years (except for the prior week). Eligible individuals then completed the draft questionnaire and other questionnaires. Participants received $20 for completed questionnaires. One day later, participants who had completed questionnaires prior to their first treatment were invited to complete the questionnaire again if they still had not started treatment. One day later, they were e-mailed a link to the online questionnaire and asked to complete it again within 7 days. Participants received $10 for completing the second questionnaire.

Measures To assess criterion validity, the six-item treatment Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ), [7] the four-item Acupuncture Expectancy Scale, [8] and a single question asking how helpful the participant believed the treatment would be for their CLBP were administered. [4, 8, 12–17] The CEQ includes two subscales (treatment credibility and treatment expectations). The CEQ has demonstrated construct validity and relationships with clinical outcomes. [4] The four-item Acupuncture Expectancy Scale, which assesses patients’ expectations for the efficacy of acupuncture, has demonstrated validity and reliability. [8] It was adapted by replacing “illness” with “pain” and, for non-acupuncture treatment, by replacing “acupuncture” with the treatment the participant was beginning. The single CLBP treatment helpfulness question [12-17] asks respondents to rate their expectations of a treatment being effective for their back pain on a 0 (no change) to 10 (complete change) scale.Evaluation of EXPECT questionnaire in randomized controlled trials

Participants, setting, and procedures After the draft questionnaire was developed, it was evaluated in three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CAM therapies for chronic pain: Back to Health (BTH), [18] Mind–Body Approaches to Pain (MAP), [19] and Pain Outcomes Comparing Yoga versus Structured Exercise (POYSE; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01797263). The BTH trial randomized participants with CLBP to yoga, physical therapy, and self-care education. Questionnaire data, completed before starting treatment, were obtained from 72 people randomly assigned to either physical therapy or yoga. The MAP trial [19] randomized participants with CLBP to group cognitive–behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction. Participants (n = 72) were invited to complete the draft questionnaire within 1 week of their first treatment session, and were paid $20 for completing the questionnaire. The POYSE trial randomized veterans with fibromyalgia to yoga or structured exercise classes. Participants (n = 100) completed the paper version of the draft questionnaire after randomization and before treatment began. In all three trials, participants also provided demographic data and pain intensity ratings. Participants in BTH and MAP completed the 23-item modified Roland Modified Disability Questionnaire, [20] and POYSE participants completed the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Revised. [21] Participants were required to have had pain for 12 weeks and to rate their pain as ≥3 on a 0–10 scale.

Statistical analyses

Initial psychometric analyses: community sample The psychometric properties of the draft questionnaire were examined in the community sample to develop the final questionnaire. Items with >5% “not applicable” responses were excluded. Next, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to determine the number of factors and to select items for the final questionnaire. The factor solutions were obtained via a minimum residual approach using R v3.2.022 and the psych package. [23] The two-factor solution was obtained using Promax rotation, allowing factors to correlate. One- and two-factor solutions were compared based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), [24] proportion of total variance explained, factor loadings, and fit statistics. Models with a lower BIC are favored. The fit statistics included those that do not assume multivariate normality (standardized root mean square of the residual [SRMSR]; <0.08 suggests a good fit) [25] and other statistics that assume a multivariate normal structure. These included the chi-square test of perfect fit (non-significant p-values >0.05 are desirable), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; <0.08 suggests a good fit), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; >0.95 suggests a good fit). [26]

As detailed in the Results, a two-factor model was selected, and then items for the final questionnaire were selected based on factor loadings. Items were retained that loaded >0.50 on the primary factor and that loaded <0.30 on the secondary factor. The final questionnaire was scored as the mean of the answered expectations questions. Scores could range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more favorable expectations. For the final questionnaire, floor and ceiling effects (defined as >15% having the highest or lowest possible score [27]), Cronbach's alpha to assess internal consistency (≥0.70 is considered adequate [28]), and corrected item–total correlations were evaluated. Test retest reliability of the questionnaire was assessed in the test–retest subgroup of the community sample using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), with ≥0.70 considered adequate. [29] Criterion validity of the questionnaire was assessed by calculating Pearson correlations with the other measures of expectations.

Psychometric evaluation in clinical trials samples Although the RCT samples completed all 18 draft questions, only the final 10-item questionnaire was scored. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) was conducted to assess the factor structure of the final questionnaire in the RCT samples using the lavaan package. [30] The CFA was fit via maximum likelihood. Fit was examined using the chi-square test of perfect fit, RMSEA, TLI, and SRMSR. To assess fit without the assumption of multivariate normality, robust test statistics using sandwich-based covariance estimates were computed in addition to the standard minimum function test statistics. Floor and ceiling effects, item–total correlations, and Cronbach's alpha were also examined.

Short-form item selection From the final 10-item questionnaire and the questions about hopes from the draft questionnaire (see Results and Appendix A), three items were selected that were summary or general measures of expectations, rather than expectations specific to one outcome domain (e.g., mood, sleep), based on the rationale that these items were likely to be relevant for all participants and could provide adequate coverage of the construct of expectations with reduced items. One hope item was also selected to be administered but not scored. The three selected items were “how much change do you realistically expect” in: (1) your back pain, (2) the impact of your back pain on your life, and (3) the impact of your back pain on your daily activities. The short form was evaluated by examining its internal consistency (all four samples), test–retest validity (community sample only), correlation with the long form (all four samples), and correlations with the criterion measures (community sample only).

Results

Table 1

Figure 1

Table 2

Table 3 Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all samples. Across the samples, diversity in age, race/ethnicity, and sex was represented, although few adults >70 years of age were included by design.

Initial psychometric analyses in community sample

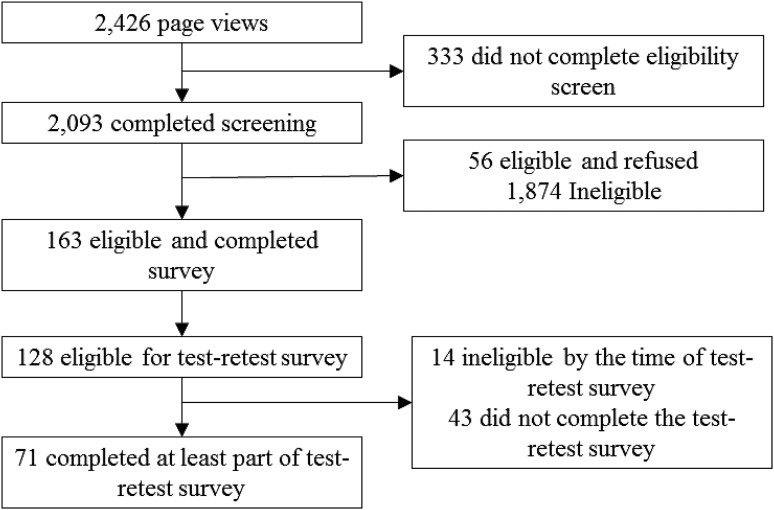

Figure 1 shows the study flow in the community sample (n = 163, n = 71 for test–retest subsample). Table 2 shows, for each item, the number of missing/not applicable responses, the mean (SD) rating, corrected item–total correlations, and factor loadings in the one- and two-factor solutions in the EFA. The corrected item–total correlations were acceptable (0.60–0.88). [31] Before factor analyses, one question (about impact of back pain on family/friends) was excluded because 9.8% (n = 10) of the sample reported that the question was not applicable. All other items had <5% not applicable or missing responses. This left complete data from 141 participants for the EFA. The EFA factor loadings indicated that the two-factor solution consisted of one factor conceptually related to expectations (items 2, 4–8, and 10–13) and the other factor conceptually related to hopes (items 1, 3, 9, 15, and 17). Two items (16 and 18) concerning expectations of outcomes in 1 year loaded on both factors.

The two-factor solution had better fit statistics and explained more variance compared with the one-factor solution (Table 3). In addition to eliminating the question about impact of back pain on family/friends, four other questions were eliminated, resulting in a 10-item final questionnaire. Items 16 and 18 were eliminated because they loaded on both factors. Items 15 and 17 were eliminated because although they loaded on the hope factor, they measured hope for a time frame that differed from that for the other three hope questions. Based on these results, 10 items about expectations were chosen for the final questionnaire to be scored, and three questions about hopes (1, 3, and 9) were chosen to be administered but not scored.

Table 4 Reliability and validity statistics for the final 10-item EXPECT questionnaire (scored from the 18 draft questionnaire items administered) are shown in Table 4. Cronbach's alpha (internal consistency) was very high (0.96). Floor (<2% had a score of 0) and ceiling (3% had a score of 10) effects were low in the community sample. In the community sample subgroup that completed the expectations questions on two separate occasions, the test–retest ICC was 0.75 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.63–0.84), consistent with expectations being a moderately stable construct over a short time period before treatment. The Pearson correlations of the 10-item EXPECT questionnaire with other measures of expectations ranged between 0.54 and 0.65 (Table 4).

Psychometric evaluation in clinical trials samples

Table 5 Tables 3 and 5 display psychometric statistics, factor loadings, and fit statistics for the 10 expectation items of the final EXPECT questionnaire completed in the three clinical trial samples. CFA were limited to individuals in the clinical trials with non-missing values (55/72 for the BTH trial, 41/72 for MAP, and 85/100 for POYSE). In all three trials, the maximum likelihood fit statistics demonstrated some lack of fit. In contrast, the robust fit statistics indicated good fit. Using the combined data from the three RCT samples, Cronbach's alpha was 0.96, indicating high internal consistency. Corrected item–total correlations across the three trials ranged from 0.61 to 0.90, further indicating sufficient reliability. Floor and ceiling effects were minimal; no individuals had a score of 0 and only 7 (2.9%) had a score of 10.

Short-form evaluation

In the four samples combined, the three-item short form showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.89; 95% CI 0.81–0.96). In the subsample that completed the questionnaire twice, test–retest stability was 0.79 (95% CI 0.69–0.89). Pearson correlations between the short form and the parent questionnaire ranged from 0.90 to 0.95 across the four samples. In the community sample, the three-item short form correlated moderately with the CEQ total score (0.64), credibility subscale (0.54), expectancy subscale (0.67), Acupuncture Expectancy Scale (0.51), and the single expectations item (0.56).

Discussion

The EXPECT questionnaire assesses individuals’ expectations of outcomes of CAM treatments for chronic pain. The questionnaire showed good reliability in community and clinical trials samples of individuals with chronic pain. The factor analyses supported the conceptualization of hopes and expectations as two distinct, but related, constructs. The questionnaire was moderately correlated with other treatment expectation measures likely due to differences across measures in aspects of expectations assessed by the measures or due to one measure consisting of a single item and the restricted range of another. The short-form version also showed good reliability and validity, and was highly correlated with the parent questionnaire.

The EXPECT questionnaire includes 10 items on expectations for various outcomes relevant for adults with CLBP. It is recommended that three questions about hopes for treatment outcomes also be administered with the expectation items but not scored. The intent of these questions is to increase respondents’ focus on answering the 10 expectations questions in terms of their realistic expectations as opposed to their hopes for treatment outcomes. Data to support the use of these three hope questions for studying hopes about treatment outcomes are not available. For the short-form questionnaire, the administration of the first hope item (“How much change do you hope for in your back pain?”), followed by the three short-form expectation items, is recommended, giving a total of four items administered. As with the parent questionnaire, only the expectation items in the short form are included in the scoring.

The EXPECT questionnaire has advantages compared with previous measures of treatment expectations. The Acupuncture Expectancy Questionnaire was found to have floor and ceiling effects [8]; the EXPECT questionnaire did not have floor or ceiling effects. Unlike CAM-treatment specific expectations measures, [8] this questionnaire was developed for use with diverse CAM treatments. In contrast to measures that assess treatment credibility [32] (i.e., a treatment's potential ability to improve pain in general), the EXPECT questionnaire asks about expectations in terms of the effects of the treatment on the respondent's own pain outcomes. Finally, the EXPECT questionnaire asks about multiple outcomes related to chronic pain, whereas other measures (e.g., mood and sleep) assess expectations for only a few outcomes. [8]

This study had a number of limitations. In the EFA, many of the fit statistics based on multivariate normality exceeded cutoff values. However, one of the main purposes of the factor analysis was to compare one- and two-factor models to determine whether hope and expectations are different rather than to compare models to cutoffs or to test the multivariate normality. The CFA, despite small sample sizes, showed adequate fit with the robust test statistics. The samples included few individuals ≥70 years of age. The study did not evaluate empirically whether including the hope items affected responses to the expectation questions. Finally, the full or short-form questionnaires, once finalized, were not evaluated in new samples.

The strengths of the study include development of the questionnaire using a sequential process of qualitative interviews with practitioners and individuals with chronic pain, cognitive interviews, and psychometric evaluation. Other strengths are questionnaire testing in samples diverse in sociodemographic characteristics and CAM therapies, and confirmatory testing in samples of individuals beginning clinical trials. The POYSE sample consisted of adults with fibromyalgia but showed results consistent with those in the CLBP samples, supporting the use of the questionnaire in diverse pain populations. A strength of the short-form development was selection of items based on item content rather than empirical selection. Selection of items for a short form solely through empirical methods can lead to omission of important aspects of the construct. [33]

Conclusions

The EXPECT questionnaire can be used in research to assess individuals’ expectations of treatments for chronic pain. Several directions for future research are indicated. Further research is needed to assess the psychometric characteristics of the EXPECT questionnaire and short form in samples with different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Examination of the association of EXPECT scores with outcomes after CAM treatments may help increase knowledge about the role of individuals’ expectations in their outcomes after CAM treatments. Finally, although the questionnaire can be used with individuals beginning CAM treatments for CLBP, the questionnaire might be adapted for use with individuals with other pain problems and for use with non-CAM treatments.

Appendixes

Appendix A: Expectations for Complementary and Integrative Treatments (EXPECT) Questionnaire

Appendix B: Short Form of the EXPECT Questionnaire

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Healthcare (grant number R01 AT005809).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References:

Thomas E, Croft PR, Paterson SM, et al.

What influences participants’ treatment preference and can it influence outcome?

Results from a primary care-based randomised trial for shoulder pain.

Br J Gen Pract 2004;54:93–96 [PMC free article]Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Thorpe L, et al.

Randomised controlled trial of a short course of traditional acupuncture compared with usual care

for persistent non-specific low back pain.

BMJ 2006;333:623Galer BS, Schwartz L, Turner JA.

Do patient and physician expectations predict response to pain-relieving procedures?

Clin J Pain 1997;13:348–351Smeets RJ, Beelen S, Goossens ME, et al.

Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and

cognitive–behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain.

Clin J Pain 2008;24:305–315Goldstein MS, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, et al.

The impact of treatment confidence on pain and related disability among patients with low-back pain:

results from the University of California, Los Angeles, low-back pain study.

Spine J 2002;2:391–399; discussion 399–401.Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, et al.

Lessons from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient expectations and treatment effects.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1418–1424Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD.

Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire.

J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2000;31:73–86Mao JJ, Armstrong K, Farrar JT, et al.

Acupuncture expectancy scale: development and preliminary validation in China.

Explore (NY) 2007;3:372–377 [PMC free article]Schafer LM, Hsu C, Eaves ER, et al.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) providers’ views of chronic low back pain patients’

expectations of CAM therapies: a qualitative study.

BMC Complement Altern Med 2012;12:234Hsu C, Sherman KJ, Eaves ER, et al.

New perspectives on patient expectations of treatment outcomes: results from qualitative interviews

with patients seeking complementary and alternative medicine treatments for chronic low back pain.

BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:276Sherman KJ, Eaves ER, Ritenbaugh C, et al.

Cognitive interviews guide design of a new CAM patient expectations questionnaire.

BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:39Cherkin DC, Eisenberg D, Sherman KJ, et al.

Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and

self-care education for chronic low back pain.

Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1081–1088Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, et al.

Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial.

Ann Intern Med 2005;143:849–856Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Ichikawa L, et al.

Treatment expectations and preferences as predictors of outcome of acupuncture for chronic back pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1471–1477 [PMC free article]Beckmann AM, Kiviat NB, Daling JR, et al.

Human papillomavirus type 16 in multifocal neoplasia of the female genital tract.

Int J Gynecol Pathol 1988;7:39–47Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, et al.

A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain:

a randomized, controlled trial.

Ann Intern Med 2011;155:1–9 [PMC free article]Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, et al.

A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain.

Arch Intern Med 2011;171:2019–2026 [PMC free article]Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Delitto A, et al.

Yoga vs. physical therapy vs. education for chronic low back pain in predominantly minority populations:

study protocol for a randomized controlled trial.

Trials 2014;15:67Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, et al.

Comparison of complementary and alternative medicine with conventional mind–body therapies for

chronic back pain: protocol for the Mind–body Approaches to Pain (MAP) randomized controlled trial.

Trials 2014;15:211Roland M, Fairbank J.

The Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire.

Spine 2000;25:3115–3124Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, et al.

The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties.

Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R120R Core Team. R:

A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014Revelle W. pysch:

Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. 1.5.4 ed.

Evanston, IL: Northwestern University, 2015Schwarz G.

Estimating the dimension of a model.

Ann Stat 1978;6:461–464Browne M, Cudeck R.

Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit.

London: Sage, 1993Hu LT, Bentler PM.

Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives.

Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6:1–55Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al.

Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires.

J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:34–42Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH.

Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994Fayers PM, Machin D.

Quality of Life. Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation.V Chichester, England: Wiley, 2000Yves R. Iavaan:

an R package for strucutral equation modeling.

J Stat Softw 2012;48:1–36Everitt BS.

The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics. 2nd ed.

New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002Prady SL, Burch J, Vanderbloemen L, et al.

Measuring expectations of benefit from treatment in acupuncture trials: a systematic review.

Complement Ther Med 2015;23:185–199Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Anderson KG.

On the sins of short-form development.

Psychol Assess 2000;12:102–111

Return to OUTCOME ASSESSMENT

Since 3-04-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |