Patient Attitudes, Insurance, and Other Determinants of

Self-referral to Medical and Chiropractic PhysiciansThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Am J Public Health 2003 (Dec); 93 (12): 2111–2117 ~ FULL TEXT

Rajiv Sharma, PhD, Mitchell Haas, DC, and Miron Stano, PhD

Department of Economics,

Portland State University,

Portland, OR 97230, USA.

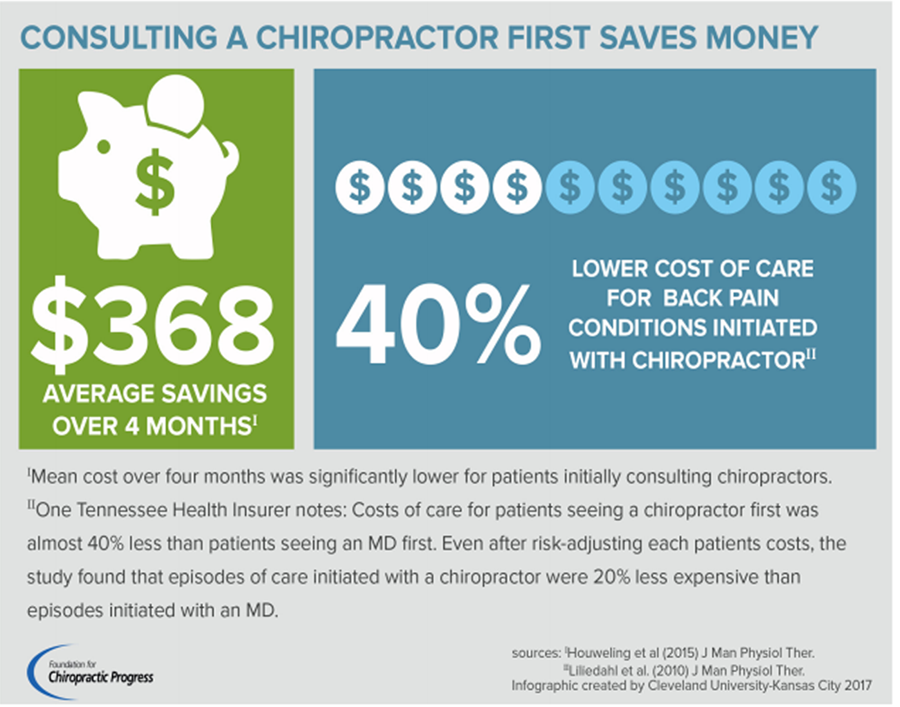

FROM: Houweling, JMPT 2015 Liliedahl, JMPT 2010Objectives: This study identified predictors of patient choice of a primary care medical doctor or chiropractor for treatment of low back pain.

Methods: Data from initial visits were derived from a prospective, longitudinal, nonrandomized, practice-based observational study of patients who self-referred to medical and chiropractic physicians (n = 1,414).

Results: Logistic regression showed differences between patients who sought care from medical doctors vs chiropractors in terms of patient health status, sociodemographic characteristics, insurance, and attitudes. Disability, insurance, and trust in provider types were particularly important predictors.

Conclusions: The study highlights the importance of patient attitudes, health status, and insurance in self-referral decisions. The significance of patient attitudes suggests that education might be used to shape attitudes and encourage cost-effective care choices.

From the Full-Text Article:

BACKGROUND

The rapid growth of chiropractic treatment and its role as the dominant form of nonmedical care [1–4] could have substantial implications for the cost and quality of health care. Despite this growth, our understanding of why patients choose chiropractic treatment remains limited. A recent literature review [5] attributes chiropractic’s popularity to the art of medicine [6] where “in response to the countless requests for the treatment of pain, chiropractors have consistently offered the promise, assurance, and perception of relief.” [5](p2222) Although this view provides considerable insight as well as a valuable message to the larger medical community, policymakers and decisionmakers in health care organizations need more systematic quantitative information about the factors that drive patient demand for chiropractic care.

Early empirical studies of chiropractic users dealt with either chiropractic patients’ characteristics, which they compared with those of the population at large, or the determinants of chiropractic utilization without reference to other providers. [7, 8] Subsequent articles compared chiropractic users with nonusers but did not control for the condition that prompts a patient to seek care. [9, 10] To overcome this deficiency, RAND investigators compared chiropractic patients with those who saw other providers specifically for back pain, the condition that a chiropractor (DC) most often treats. Logistic regression estimates indicated that chiropractic users were more likely to be male and White with a high school education. [11] None of the health status or health attitude variables were determinants of provider choice.

Two other major studies were subsequently conducted on patients with low back pain (LBP). Through stepwise logistic regression comparisons of 1992 data from a sample of North Carolina patients, Carey et al. [12] found only 3 independent predictors: those who chose chiropractic treatment were more likely to be in better health, have milder pain, and have adequate insurance (insurance other than Medicaid or Medicare only, or no insurance). Hurwitz and Morgenstern [13] drew on the 1989 National Health Interview Survey and found a variety of differences, for example, non-Whites and persons with disabling comorbidities were less likely to use chiropractic care than medical care, whereas the unmarried, unemployed, or high school graduates were more likely to use chiropractic care. Age, family income, self-perceived general health status, and type of insurance coverage (Medicare only, Medicare plus private, private fee-for-service, private prepaid, other, none) had no effect on patient choice.

More recent results from a survey conducted in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan showed that nearly half of patients with neck pain or LBP sought care from DCs alone or DCs in combination with other providers. [14] Logistic regressions indicated that those who consulted a DC alone had fewer comorbidities, were younger, and were more likely to live in urban areas and have better physical and social functioning than those who saw a medical doctor (MD) alone. In contrast, findings from another recent study of patients with back and neck problems showed that chiropractic patients were comparable with those treated by MDs, although the patients studied had significantly poorer functioning than the general population. [15] Also, by confirming that chiropractic patients and DCs share similar beliefs about the central tenets of chiropractic practice, this study suggested that such beliefs may be an important predictor of patients’ self-referral decisions.

The literature has clearly evolved, but though recent studies provide sophisticated analyses of patients’ choice between MDs and DCs, many contradictions can be found in the results. In particular, the effects of health status and third-party payment remain unclear, and the effects of patient attitudes have gone largely untested. To help resolve these differences and to generate more definitive evidence, we drew on a comprehensive database that contains extensive clinical, attitudinal, and socioeconomic information for a large sample of patients with LBP who self-referred to either MDs or DCs. The purpose of this study was to identify the salient determinants of patient choice between MDs and DCs for the treatment of LBP.

METHODS

Data Source

Our data were derived from the baseline of an ongoing prospective, longitudinal, nonrandomized, practice-based observational study of patients who self-referred to MDs and DCs. [16, 17] Consecutive patients (n = 2,872) aged 18 or more years with a primary complaint of LBP were enrolled at 14 multi-MD practice clinics and 51 DC clinics between December 1994 and June 1996. Except for 1 MD clinic in the state of Washington, all other clinics were located in Oregon. All participants were required to sign a consent form that explained the study and the participant’s rights. The study was approved for protection of human subjects by the Western States Chiropractic College Institutional Review Board. The study protocol [16] and patient sample [17] have been previously reported in detail.

Information collected upon enrollment included LBP history, duration, and severity of current episode, as well as comorbidities, demographics, insurance characteristics, and selected psychosocial factors. Severity of present pain was measured by a 100–mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score, where a score of 0 denotes “no pain” and a score of 100 denotes “excruciating pain.” [18] Functional disability was measured with the Revised Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. [19] The 10 questions address pain and daily activities — pain intensity, personal care, lifting, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, social life, traveling, and changing degree of pain — on a 6–point scale. These questions are used to create a 100–point scale; higher scores indicate greater dysfunction. Episode characteristics and questions related to sciatica were assessed through InterStudy’s Low Back Pain TyPE Specification. [20] Patients were screened for current and past comorbidity for headache, arthritis/rheumatism, gastrointestinal problems, gynecological problems, hypertension, asthma/chronic cold or allergies, and any other chronic condition.

Psychosocial measures included questions related to stress and confidence in successful treatment outcome, a depression screen, and the 2 subscales of the Krantz Health Opinion Survey (HOS). [21] The Behavioral Involvement subscale measures patient attitudes toward self-care and active behavioral involvement in medical care (range = 0–9). The Information subscale assesses patient desire to ask questions and be informed about medical decisions (range = 0–7). Higher scores indicate more favorable attitudes. A 3–item depression questionnaire was used to screen for major depression/dysthymia. [22, 23] For the analysis, depression was defined as a positive screen for major depression/dysthymia.

Six–point Likert scales were used to evaluate stress (low to high) associated with the patient’s work or school, home, and financial situation. Confidence in the selected provider’s ability to successfully treat the patient’s LBP problem was measured through a 6–point Likert scale, from “extremely certain” to “extremely uncertain.” Beliefs about health care were also evaluated on 6–point Likert scales from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Patients were asked if they trusted DCs, trusted MDs, were against taking prescription drugs, and believed in the equality of MD and DC skills in the treatment of LBP. All of these variables were dichotomized for the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Table 1

Table 2 Characteristics of patients who chose DCs and MDs, respectively, were tabulated and compared using t tests and χ2 statistics. Logistic regression was used to model the patient’s decision to seek care from DCs rather than from MDs. Independent predictors of care-seeking were identified by backward elimination of variables with P > .05. This procedure was applied to potential predictors comprising race, age squared, current or past headache, and sciatica, in addition to all variables listed in Table 1. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by means of forced entry of all variables into the model to determine the effect of variable elimination on the odds ratio (OR) in Table 2. Finally, we used estimates from the logistic model to estimate the marginal impacts on the probability of choosing a DC

To evaluate the effect of missing data, we used a χ2 test to compare choice of provider for the cohorts of patients, with and without missing data. We further computed the predicted choice for the average profile of the 2 patient cohorts. Analysis was performed using SAS 8e software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Predictors of Patient Choice

The choice of variables to include in the model was based on a priori expectations of importance, models found in the literature, and the descriptive comparisons from our data. The social and demographic variables were sex, age and age squared, race, education, marital status, income ( > $36,000), smoking, and employment. Variables that measured the impact of financial incentives were private insurance (whether or not it paid for LBP treatment) and the patient’s expected principal payer (self-pay, private health insurance or Medicare, Medicaid or Oregon Health Plan, workers’ compensation, another person’s auto insurance, other). Baseline VAS and Oswestry scores measured the potential impact of pain and disability. Other health status characteristics included were past history of LBP, sciatica or pain radiating above or below the knee, and LBP phase (with acute and chronic LBP demarcated by current episode duration of 6 weeks). [24–26] Additionally, we included depression, present and past headache, and the number of prior and current health conditions reported.

Subgroup analysis was performed to determine the consistency of identified predictors across key subgroups. The selection of subgroups was based on characteristics suggested by the literature as potential predictors (sex, age, acute and chronic LBP, history or no history of LBP), or on characteristics that were found to be important from the primary logistic model (insured and self-pay, trusts MDs, and trusts DCs).

RESULTS

Of the 2,872 patients enrolled in the study, 1,414 (49.2%) were included in the primary analysis because they had complete data for all variables included in the backward elimination process. A subsequent sensitivity analysis was conducted with 1,598 patients (55.6%) who had complete data for all variables that remained in the final logistic model of the primary analysis. Most data were available for almost all patients, so we were able to accurately profile excluded patients and their provider choices. The 2 cohorts of patients included and excluded from the model differed in characteristics we identified as predictors of provider choice. For example, excluded patients were more likely to have their care paid by insurance, whereas those included in the model were more likely to self-pay (P = .01). Excluded patients actually chose MDs approximately 10% more often than included patients (P < .0001). When mean profiles were used to calculate the difference in rates of MD and DC choice for excluded and included patients, excluded patients choose MDs about 11% more often than patients included in our regressions. The success of the logistic model (see Table 2 and “Independent Predictors of Patient Choice”) in predicting choice of patients excluded from the primary analysis suggests minimal impact of missing data on the model.

Comparison of Patient Characteristics

Table 1 indicates many differences between patients who chose MDs versus DCs. These differences can be placed into 4 categories: health status, sociodemographic, insurance, and attitude. Health status indicators associated with choice of MDs include greater pain, greater functional disability, and chronic LBP. Self-referral to DCs was associated with history of LBP and acute LBP. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with choice included age, smoking, and employment status. There was no important association between provider choice and income, education, and other sociodemographic characteristics (not shown in Table 1). The financial incentives and other constraints faced by patients who chose between MDs and DCs are likely to vary according to whether patients have health insurance that is expected to pay for their LBP treatment, and this likelihood is clearly supported by the results. The relatively high proportion of self-pay patients who selected DCs is especially dramatic. Finally, each indicator of patient attitudes is associated with patient choice of provider.

Independent Predictors of Patient Choice

The final logistic model (n = 1,414), presented in Table 2, confirms the importance of disability and payer type as well as patient attitudes and trust in the provider. Sensitivity analysis that used forced entry of all potential predictors into the model left the ORs for all variables reported in Table 2 essentially unchanged. Furthermore, when the analysis was repeated with only the variables in Table 2, the results for the 1598 patients with complete data for these variables were also essentially the same as reported in Table 2.

Greater disability, as measured by the baseline Oswestry score, reduces the likelihood that a patient will select a DC (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.97, 0.98). With Oswestry scored on a 100–point interval, large differences in disability scores can have a major impact on the probability of provider choice, even when the OR is close to unity. Baseline VAS was eliminated from the choice model once Oswestry was included because of redundancy between the 2 variables (r = 0.65).

Of the sociodemographic variables, age squared, income, and “other” marital status were predictors, with older and higher-income patients more likely to select DCs. Employment status ceased to be significant once payer identity was included in the logistic regression, possibly because employment often determines health insurance coverage.

Each of the payer categories had dramatically large ORs. Patients who expected their care to be paid for by third parties were much more likely to choose MD treatment when compared with self-pay patients (OR ≤0.24). This effect was especially pronounced for Oregon Health Plan patients, as reflected in the very low OR of 0.025 (95% CI = 0.01, 0.06).

The logistic analysis also shows variables measuring patients’ attitudes to have substantial ORs. Patients who placed trust in MDs were much more likely than patients lacking such trust to seek care from MDs, with a similar pattern for patients who trust DCs (OR = 27.30, 95% CI = 16.23, 45.93). Also, patients who were opposed to prescription drugs were more likely to choose DCs (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.11, 2.22). Patients who expressed confidence in the ability of their chosen providers to successfully treat their LBP were more likely to obtain care from DCs (OR = 6.08, 95% CI = 3.84, 9.63) than were patients who lacked such confidence. However, those who believed that MD and DC providers are equally skilled were much more likely to obtain care from MDs (OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.28, 0.54). The results also show that patients with more favorable attitudes toward self-directed treatment and active behavioral involvement were somewhat more likely to choose DCs (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.21).

Table 3 To illustrate the impact of predictor variables on provider choice, the marginal effects on the probability of choosing a DC for a representative patient were calculated in Table 3 from the estimates presented in Table 2. Differences in the trust and payer variables as well as in some continuous variables such as age and Oswestry score have dramatic effects on provider choice. Consider a married, self-pay patient aged 40 years who has an Oswestry score of 40 and a HOS behavior subscale score of 5. The patient is opposed to taking prescription drugs, does not trust MDs or DCs, does not believe that MDs and DCs are equally skilled in treating LBP, and lacks confidence in his or her physician’s ability to successfully treat the low back condition. The estimates from Table 2 indicate that the probability that this patient will select a DC is 0.78. Had the patient expressed trust in MDs, the probability that this patient would select a DC would have decreased to 0.25. If payment for treatment were by insurance instead of self-pay, the probability that treatment would be sought from a DC would have decreased from 0.78 to 0.23. If the patient’s baseline Oswestry score were 80 instead of 40, the probability that treatment would be sought from a DC would have decreased from 0.78 to 0.55.

Table 4 Attitudes and the identity of the expected payer remain important predictors across most patient subgroups. The OR estimates for these predictors as well as for Oswestry and HOS are shown in Table 4 for several subgroups (other results are available on request). The insurance categories generally had sizeable effects on choice as illustrated for the acute and chronic patients. Similarly, the attitude variables also tended to have sizeable effects, though we found some differences across subgroups. For example, when the insured and self-pay patients were compared, opinion variables except attitudes to behavioral involvement had greater magnitudes and were more likely to be statistically significant for insurance-pay than for self-pay patients. This suggests that attitudes may be less important when the choice of provider has a large financial impact.

DISCUSSION

Ambulatory and inpatient back care comprise a substantial and growing portion of this nation’s health care budget. Mainstream medicine’s record in treating LBP is poor. Evidence has already shown that many surgical and nonsurgical hospital admissions are unnecessary. [27] However, factors other than medicine’s questionable record contribute to the popularity of chiropractic. These factors include the high satisfaction chiropractic patients report from their care, [12, 17, 28] the strength of the patient–provider relationship and the art of medicine practiced by DCs, [5, 6] and practice guidelines that recommend spinal manipulation for some patients with LBP. [29] Third-party payers have responded to patient preferences and this new information by improving access to or increasing benefits for alternative forms of care. Some managed care organizations are even examining the potential cost and quality benefits of the integration of allopathic and alternative approaches.

A major limitation to more complete integration is the lack of reliable empirical evidence on costs, outcomes, and forces that influence patient choice of provider. The proportion of articles indexed in the MEDLINE database under “alternative medicine” was just 0.4% over the period 1966–1996, and only 120 of the 400,000 MEDLINE additions per year dealt with chiropractic. [30] Our work is intended to help fill some of the information gaps on the determinants of chiropractic utilization for low back care.

Our results regarding patient health status, opinions and attitudes, and source of payment are clear and robust. We found that patients with less disability are more likely to select DCs than MDs. We also found that the source of payment for care is very important. Insurance coverage for chiropractic services is often more limited than coverage for medical care. Data from 1993 and 1995 indicated that only 75% of those with private coverage had chiropractic benefits (only 44% for HMO enrollees), and that most who did have such benefits faced coverage restrictions such as visit or dollar limits. [31] Thus, even when fees for chiropractic care are less than fees for medical care, so that chiropractic is less costly for uninsured patients, limits on chiropractic benefits may render them more costly for insured patients. Not surprisingly, patients whose treatment is paid for by insurance, private or public, are far more likely to seek medical care; self-pay patients are far more likely to choose a DC.

In contrast to a previous study that showed no effects of attitudes on choice, [11] our analysis revealed that patient attitudes toward both their involvement in health care and prescription medicine as well as their trust in providers are important predictors of patient choice. Patients who trust DCs but are opposed to taking prescription drugs are more likely to seek chiropractic care; those who trust MDs and are not opposed to prescription drugs are more likely to seek medical care. Patients who express confidence in the provider’s ability to successfully treat their illness are more likely to seek chiropractic care than patients lacking such confidence. This result suggests that patients who choose chiropractic as opposed to medical treatment require higher expectations of relief from treatment. After controlling for all other variables, we found that those who believe that MDs and DCs are equally skilled in treating LBP are more likely to seek medical care. These last two results suggest a preference for medical care that remains to be explored.

We have identified and measured the impact of salient predictors of patient choice between medical and chiropractic treatment for LBP, but much remains to be done. Patient attitude variables identified as crucial to provider choice especially require additional research. We did not examine how patient attitudes are influenced by other factors such as patient education and experience. Our ability to generalize the findings is limited by minimal minority representation and by Oregon’s broad scope of practice for chiropractic. [32] Finally, this study also does not fully explore the complex financial incentives facing patients as they choose a provider. Chiropractic coverage is becoming a nearly universal benefit in private insurance. [33] Nevertheless, restrictions on utilization have tended to be far more severe on chiropractic care than on medical care, [31, 34] and it is unclear whether patients fully understand the nuances of our complicated insurance system, including deductibles and copayments. These questions remain to be addressed in future research.

Chiropractic and other forms of alternative medicine are being increasingly integrated into managed care, at least partly in response to patient preferences. [31, 35, 36] With evidence of differences in costs and some outcome measures (e.g., satisfaction) of low back treatment by provider type, [37–42] a patient’s choice of provider can promote economic efficiency or hinder it. Our results highlight the importance of patients’ attitudes, health status, and third-party payment in self-referral decisions. In particular, by drawing attention to the role of patient attitudes in self-referral, our work highlights the potential role of education as an indirect way to influence attitudes and thus encourage more cost-effective choices.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services (grant R18 AH10002); by a competitive challenge grant from the Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research (940502) with funds donated by the National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Corporation; and by the Consortial Center for Chiropractic Research (grant U01 AT00170).

Human Participant Protection

All participants were required to sign a consent form explaining the study protocol and participant rights. This study was approved for protection of human subjects by the institutional review boards of Western States Chiropractic College.

Contributors

R. Sharma conducted the analysis. M. Haas was responsible for design and implementation of the study. M. Stano helped design the analysis and was responsible for the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and wrote the article.References:

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Morlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL.

Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use

New England Journal of Medicine 1993 (Jan 28); 328 (4): 246–252Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575Druss BG, Rosenheck RA.

Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services.

JAMA. 1999;282:651–656Ni H, Simile C, Hardy A.

Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine by United States adults:

results from the 1999 national health interview survey.

Med Care. 2002:40:353–358Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM.

Chiropractic Origins, Controversies, and Contributions

Archives of Internal Medicine 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2215-2224Coulehan JL.

Chiropractic and the clinical art.

Soc Sci Med. 1985;21:383–390Shenk JC.

Chiropractic utilization and characteristics of users.

JACA. 1974;8:S76–S79Yesalis CE 3rd, Wallace RB, Fisher WP, Tokheim R.

Does chiropractic substitute for less available medical services?

Am J Public Health. 1980;70:415–417Cleary PD.

Chiropractic use: a test of several hypotheses.

Am J Public Health. 1982;72:727–730Shekelle PG, Brook RH.

A community-based study of the use of chiropractic services.

Am J Public Health. 1991;81:439–442Shekelle PG, Markovich M, Louie R.

Factors associated with choosing a chiropractor for episodes of back pain care.

Med Care. 1995;33:842–850Carey TS, Evans A, Hadler N, Kalsbeek W, McLaughlin C, Fryer J.

Care-seeking among individuals with chronic low back pain.

Spine. 1995;20:312–317Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H.

The effects of comorbidity and other factors on medical versus chiropractic care for back problems.

Spine. 1997;22:2254–2264Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L.

The Treatment of Neck and Low Back Pain: Seeks Care? Who Goes Where?

Med Care. 2001 (Sep); 39 (9): 956–967Coulter ID, Hurwitz EL, Adams AA, Genovese BJ, Hays R, Shekelle PG.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002; 27 (3) Feb 1: 291–298Nyiendo J, Lloyd C, Haas M.

Practice-based research: the Oregon experience.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:25–34Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goldberg B, Sexton G.

Patient Characteristics and Physicians' Practice Activities for

Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Practice-based Study

of Primary Care and Chiropractic Physicians

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 (Feb); 24 (2): 92–100Scott J, Huskisson EC.

Graphic representation of pain.

Pain. 1976;2:175–184Hudson-Cook N, Tomes-Nicholson K, Breen AC.

A revised Oswestry disability questionnaire.

In: Roland MO, Jenner JR, eds. Back pain: new approaches to rehabilitation and education.

New York, NY: Manchester University Press; 1989:187–204.User’s Manual: Low Back Pain TyPE Specification.

Version 1. Bloomington, Minn: Quality Quest; 1989.Krantz DS, Baum A, Wideman MV.

Assessment of preferences for self-treatment and information in health care.

J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:977–990Smith GR, Burnam MA, Burns BJ, Cleary PD, Rost KM.

Outcomes Management Form 8.0: TyPESM Specification.

St. Paul, Minn: InterStudy; 1990.Smith GR, Burnam MA, Burns BJ, Cleary PD, Rost KM.

User’s Manual: Depression TyPESM Specification.

St. Paul, Minn: InterStudy; 1990.Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders.

A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders.

Spine. 1987;12(Suppl 7):S1–S59Philips HC, Grant L.

The evolution of chronic back pain problems: a longitudinal study.

Behav Res Ther. 1991;29:435–441Philips HC, Grant L, Berkowitz J.

The prevention of chronic pain and disability: a preliminary investigation.

Behav Res Ther. 1991;29:443–450Cherkin DC, Deyo RA.

Nonsurgical hospitalization for low-back pain: is it necessary?

Spine. 1993;18:1728–1735Cherkin, D.C. and MacCornack, F.A.

Patient Evaluations of Low Back Pain Care From

Family Physicians and Chiropractors

Western Journal of Medicine 1989 (Mar); 150 (3): 351–355Bigos S, Bower O, Braen G, et al.

Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,

Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994Barnes J, Abbot NC, Harkness EF, Ernst E.

Articles on complementary medicine in the mainstream medical literature:

an investigation of MEDLINE, 1966 through 1996.

Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1721–1725Jensen GA, Roychoudhury C, Cherkin DC.

Employer-sponsored health insurance for chiropractic services.

Med Care. 1998;36:544–553Lamm LC, Pfannenschmidt K.

Chiropractic scope of practice: what the law allows—update 1999.

J Neuromusculoskeletal System. 1999;7:102–106Cleary-Guida MB, Okvat HA, Oz MC, Ting W.

A Regional Survey of Health Insurance Coverage for Complementary and

Alternative Medicine: Current Status and Future Ramifications

J Alt Compl Med. 2001; 7 (3): 269–273Stano M, Ehrhart J, Allenburg T.

The growing role of chiropractic in health care delivery.

J Am Health Policy. 1992;2:39–45Weeks J.

The emerging role of alternative medicine in managed care.

Drug Benefit Trends. 1997:14–15,25–28La Puma J, Eiler G.

Tapping the potential of alternative medicine.

Healthc Financ Manage. 1998;52:41–44Shekelle PG, Markovich M, Louie R.

Comparing the costs between provider type of episodes of back pain care.

Spine. 1995;20:221–226Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, et al.

The Outcomes and Costs of Care for Acute Low Back Pain Among Patients

Seen by Primary Care Practitioners, Chiropractors, and Orthopedic Surgeons

The North Carolina Back Pain Project

New England J Medicine 1995 (Oct 5); 333 (14): 913–917Mushinski M.

Treatment of back pain: outpatient service charges, 1993.

Statistical Bulletin, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company;

1995(Jul–Sep):32–39.Stano M, Smith M.

Chiropractic and Medical Costs of Low Back Care

Medical Care 1996 (Mar); 34 (3): 191–204Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battie M, et al.

A Comparison of Physical Therapy, Chiropractic Manipulation, and Provision of an

Educational Booklet for the Treatment of Patients with Low Back Pain

New England Journal of Medicine 1998 (Oct 8); 339 (15): 1021-1029Stano M, Haas M, Goldberg B, Traub PM, Nyiendo J.

Chiropractic and medical costs of low back care:

results from a practice-based observational study.

Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:802–809.

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER

Return to COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Since 10-27-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |