Complementary and Alternative Medicine Practices in Military

Personnel and Families Presenting to a

Military Emergency DepartmentThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Military Medicine 2015 (Mar); 180 (3): 350354 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Carol Cancelliere, Deborah Sutton, Pierre Côté, Simon D. French, Anne Taylor-Vaisey & Silvano A. Mior

Department of Emergency Medicine,

Naval Medical Center San Diego,

34800 Bob Wilson Drive, San Diego, CA 92134.

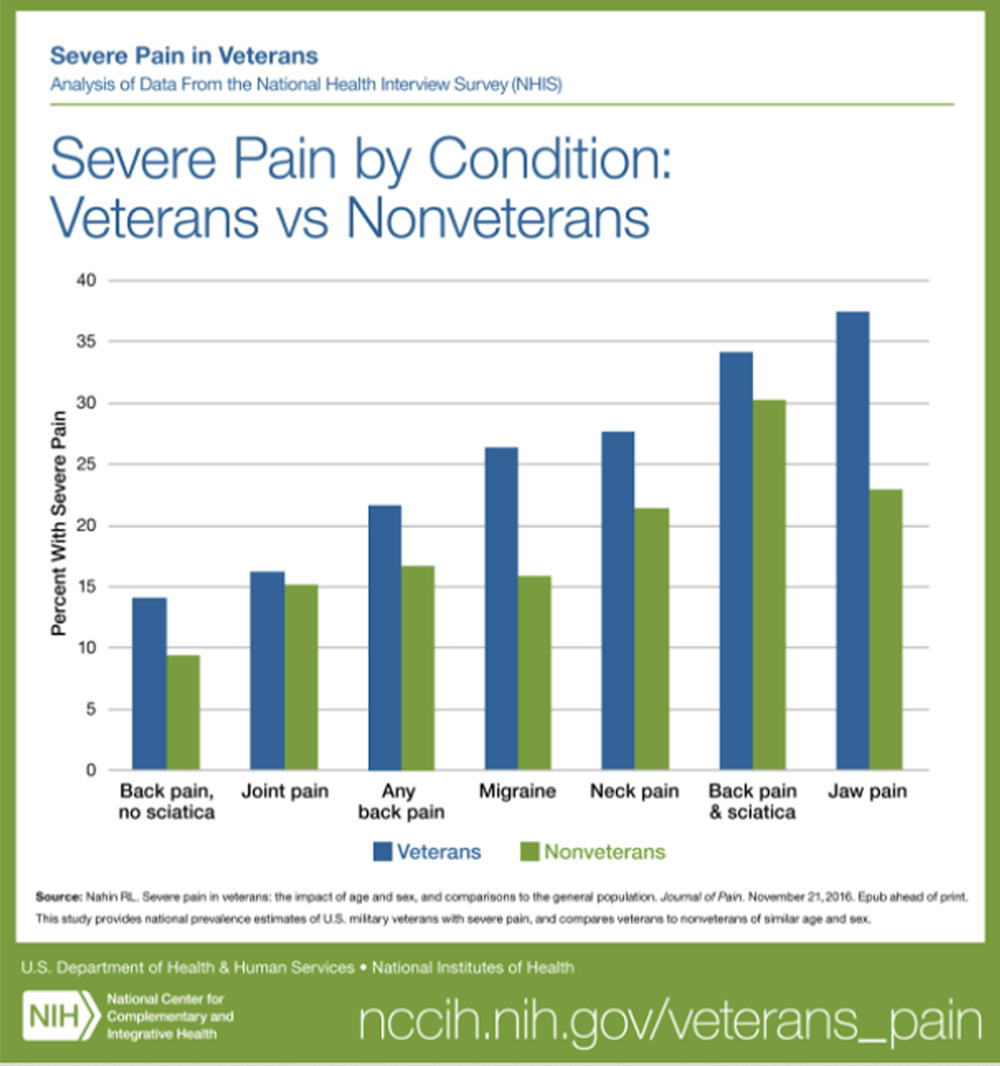

FROM: Nahin ~ Pain 2017OBJECTIVES: Limited published literature is available on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use and attitudes toward CAM in the military community. We sought to evaluate past experiences with CAM, common conditions for which CAM is used, and willingness to use acupuncture for acute conditions in an Emergency Department (ED) setting by patients and family members presenting to a tertiary military treatment facility (MTF).

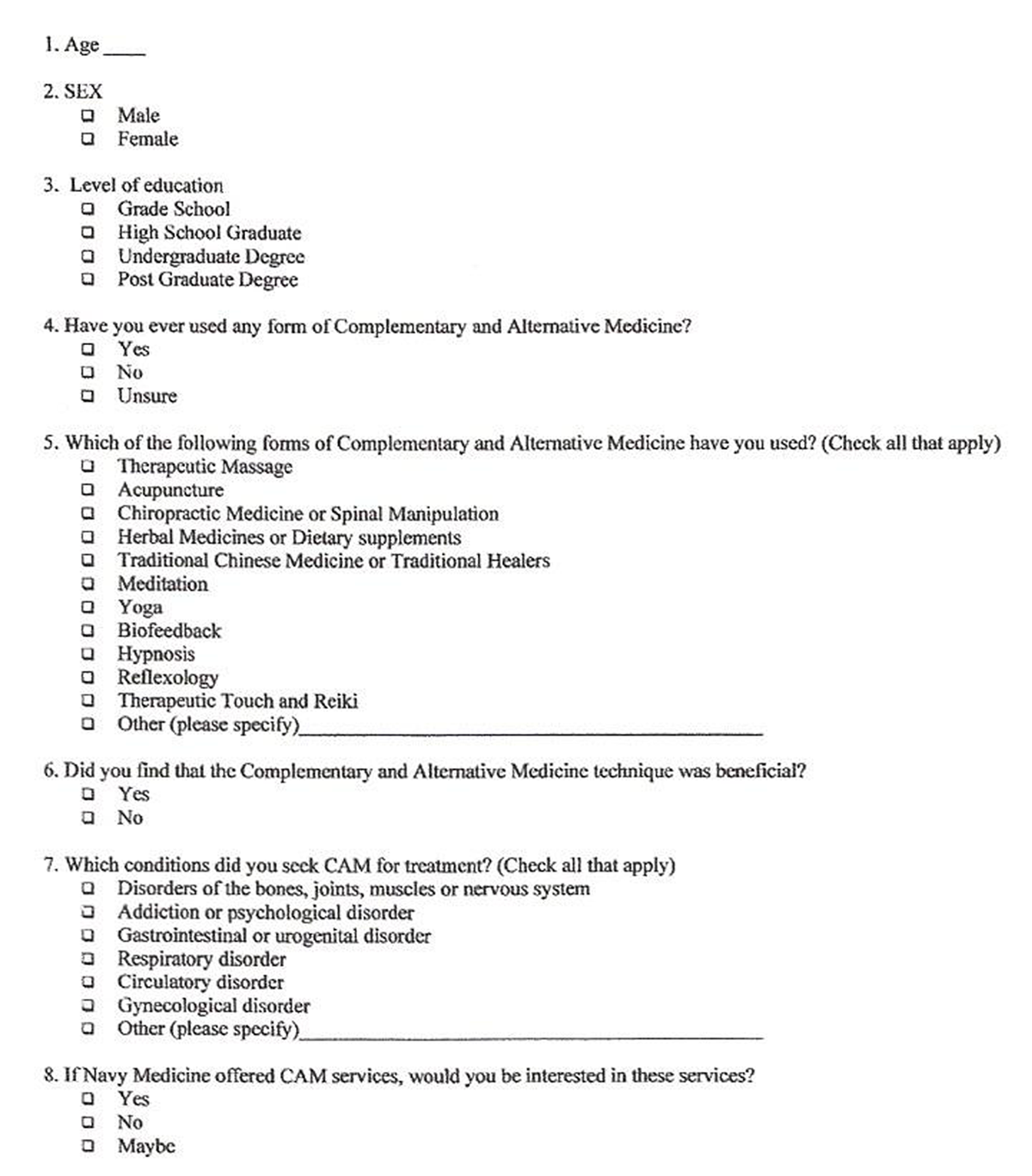

METHODS: After institutional review board approval, an 18-item questionnaire was distributed to a convenience sample of ED patients presenting to a Navy MTF.

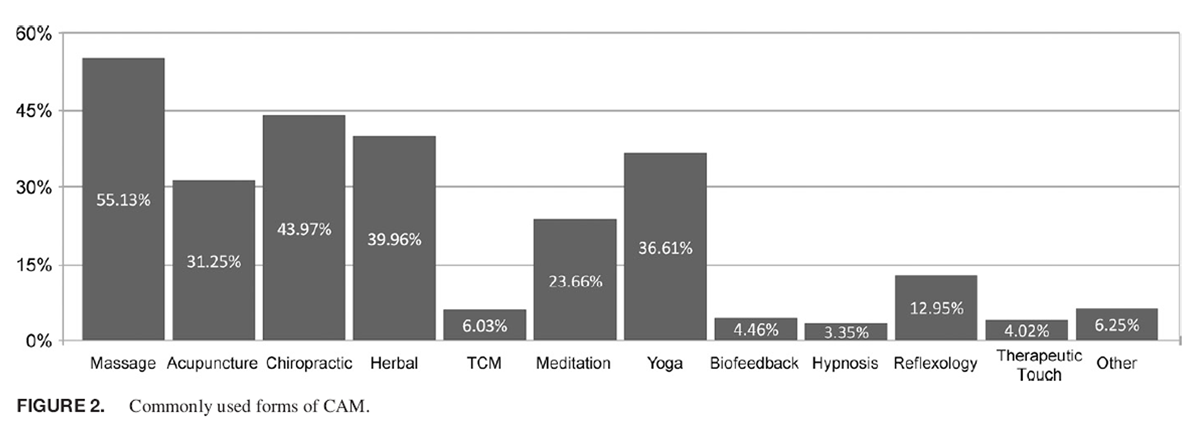

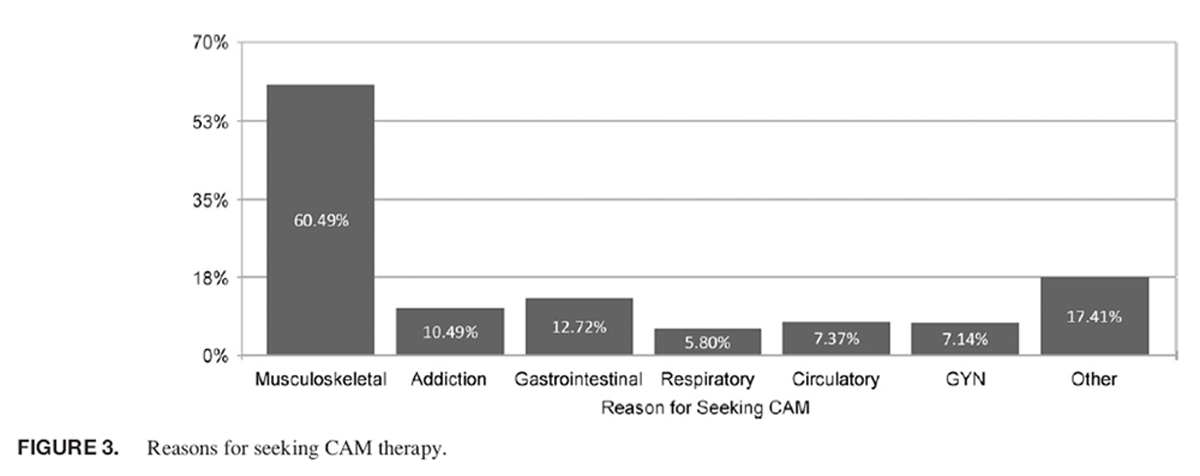

RESULTS: A response was obtained from 1,005 respondents with 45% describing previous or current CAM use. Massage, chiropractic, herbal, and acupuncture were most frequently employed. The most common reasons for use of CAM therapies are described. The majority (88%) of surveyed participants reported that CAM therapies should be offered by the MTF and 80% reported a willingness to use acupuncture in the ED setting.

There is more like this at our

CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS PageCONCLUSION: CAM therapies are used by the military community for a wide variety of conditions. The use of acupuncture in the ED for treatment of presenting complaints was met with interest by respondents. Further studies are necessary to determine indications, efficacy, and patient satisfaction with such therapy in an emergent setting.

From the FULL TEXT :

INTRODUCTION

First established as the Office of Alternative Medicine in 1991 and later reestablished in 1998, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) is one of the centers of the National Institutes of Health. The mission of NCCAM is to define, through rigorous scientific investigation, the usefulness and safety of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) interventions and their roles in improving health and health care. [1] NCCAM defines CAM as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally part of western or allopathic medicine, [2] as generally practiced by medical doctors and allied professionals such as physical therapists, psychologists, and registered nurses. Complementary medicine refers to the use of CAM therapies together with conventional medicine whereas alternative medicine refers to the use of CAM therapies in lieu of conventional medicine. [2] CAM therapies are defined by NCCAM as the use of a variety of herbal products (botanicals), mind and body medicines, such as yoga and meditation, and a variety of manipulative and body-based practices such as massage, acupuncture, qi gong, and tai chi. [2]

Previous population-based studies have demonstrated the use of CAM therapies by Americans. A study conducted in 2002 revealed that 62% of those surveyed had used one or more forms of CAM in the previous 12 months. [3] A follow-up study in 2007 showed continued use of CAM by those surveyed, but an overall increase in the prevalence of use of acupuncture. [4] A 2004 study conducted by Madigan Army base revealed that 81% of those surveyed had used 1 or more CAM therapies in the preceding year. The most popular therapies included massage and herbals for pain, stress, and anxiety. Patients generally experienced positive results and 69% of those surveyed felt that these therapies should be offered at military treatment facilities (MTFs). [5] A study conducted in an urban civilian Emergency Department (ED) in 2004 further demonstrated the use of CAM therapies with 47% of those surveyed reporting use of CAM within the previous 12 months. [6]

Most recently, the Department of Defense has funded additional research into the use of CAM, specifically acupuncture, in the treatment of a variety of conditions endemic to the military population, including traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and chronic pain syndromes in a wide variety of settings including while deployed. [710]

To date, there is a general paucity of literature regarding the use of CAM in the military ED setting. We sought to describe the regional use of and opinions regarding CAM by active and retired military personnel and their dependents presenting to a U.S. Navy tertiary care facility ED for care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Figure 1

Table 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Table 2

Table 3 In this Committee on Human Research-approved study, we approached all English-speaking individuals presenting to a U.S. Navy MTF ED for medical evaluation and treatment between January 1, 2012 and March 30, 2012 and requested that they complete a written survey regarding their personal use, experiences with, and opinions regarding CAM therapies. Research assistants were available to answer questions. Demographic data including age, gender, and level of education were also collected. See Figure 1 for the survey tool. All data were transcribed into a standardized Microsoft Excel 2008 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) spreadsheet for further analysis. Descriptive statistics were performed on the results.

RESULTS

There were 1,005 surveys collected during the study period. Not all questions were answered by all respondents. The average age of those surveyed was 36 with a median age of 31 (range 193). There were 516 females who completed the survey at least in part (51.4%). Questions regarding education were completed by 989 participants. High School graduate (550, 55.6%), completion of college (288, 29.1%), and postgraduate education (109, 11%) were the most frequently reported levels of education. Completion of grade school was described by 42 survey participants (4%) (Table I).

CAM use was described by 993 with 448 (45%) having described previous or current use. Of those reporting previous or current use of CAM therapy, massage (247, 55%), chiropractic (197, 44%), herbal (179, 40%), and acupuncture (140, 31.2%) were used most frequently (Figure 2). A perceived benefit was reported by 397 (74%) of those who had used 1 or more forms of CAM. The most commonly reported reasons for use of CAM therapies included musculoskeletal disorder or chronic pain (271, 60.5%), gastrointestinal disorder or pain (57, 12.7%), addiction (47, 10.5%), circulatory disorder (33, 7%), gynecological (32, 7%), and respiratory disorder (26, 5.8%) (Figure 3). Specific questions regarding acupuncture use were completed by 886 participants with 140 (15.7%) reporting previous use of acupuncture. An additional 487 (55%) reported a willingness to use in the future (Table II). Satisfaction with acupuncture was reported as follows: 36 extremely satisfied (26%), 44 very satisfied (31%), 36 somewhat satisfied (26%), 11 not satisfied (8%), and 13 not at all satisfied (9%).

CAM therapy recommendations by a primary care provider was described by 876 participants with 735 (84%) reporting using CAM independent of a recommendation. Discussions with a primary care provider were described by 868 survey participants with 479 (55%) reporting that they had not discussed use with their primary provider. The majority (88%) of surveyed participants (716/812 responses) reported that they felt that CAM therapies should be offered by the Department of the Navy in MTFs (Table III). A response regarding potential use of acupuncture in the ED was achieved from 832 participants. A willingness to use ED acupuncture was reported by 355 (43%) and an additional 308 (37%) reported that they might be willing to try ED acupuncture.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies evaluating the use of CAM in military populations demonstrate considerable regional variations in the use of these therapies. One study in the Pacific Northwest showed 81% of respondents had used one or more CAM therapies. [5] One from an overseas MTF in Hawaii found CAM use to be approximately 51% within the past year [11] and another looking specifically at patients in the southwestern United States showed a prevalence of 49%. [12] Prior studies looking at active duty and reserve Navy and Marine personnel show 37% of respondents had used CAM. [13]

The majority of these previous surveys evaluated patients presenting to Family Medicine or Internal Medicine clinics. [514] These patients are more likely to have adequate access to primary care. The ED is the gateway to the health care system and unfortunately is often used as the primary point of care for many individuals. For this reason, we believe that patients presenting to the ED are different in many ways from those presenting to their primary care provider. Studies looking at CAM use, specifically in the ED population, have shown that more than half (55%) of those presenting to the ED have used CAM therapies. [15] They have also shown that those who use CAM are more likely to utilize primary care and when hospitalized have a shorter length of stay. [15]

It is important to remember as Emergency Medicine providers that at least half of our patients are utilizing these therapies and including questions regarding CAM use in the history may provide important answers. Multiple studies evaluating CAM use in the ED population have found that herbals and medicinal plants were very commonly used. [1620] These can contribute to multiple drug interactions and are associated with their own toxicities. [21] Although CAM use is less prevalent in the pediatric population, herbal medications tend to be the most commonly form used. [17, 19]

Our study looked closely at acupuncture use within a specific population of patients and family presenting to the ED both historically and as a potential method of active treatment. Previous studies looking at acupuncture use in the ED setting have shown that acupuncture can be used effectively for multiple medical complaints. [2232] One study looking at auricular acupuncture for treatment of acute pain in a military ED setting found immediate improvement in pain while in the department. [31] Other studies have found similar results with immediate pain relief and a trend toward reduction in time spent in the ED for those treated with acupuncture. [32] The reasons for this perceived benefit are debated and currently lack widely accepted physiological explanation; further studies may help to elucidate these findings and potential benefits. The current body of research regarding acupuncture treatment in the ED is limited as there is no standardized treatment protocol, leaving the actual acupuncture point placements up to the individual providers. [3234]

Our study demonstrates there is an interest among the active duty military and dependent patient populations for this treatment modality with 80% either interested or willing to try acupuncture in the ED.

The results of the present study and available published literature suggest a patient interest in CAM and an openness to acupuncture as a treatment modality. This suggests acupuncture treatment in the ED as a potential modality to meet the patient interest and desire. The ideal treatment would be fast, low risk (i.e., avoid potentially dangerous needle placements with known complications), effective, and standardized for multiple painful complaints. One study used an acupuncture treatment model with only two auricular acupuncture points and had promising results in the alleviation of a variety of painful conditions. [31]

CONCLUSION

CAM therapies are used by a population presenting to a U.S. Navy MTF ED for care. The majority of those who had used CAM therapies in the past reported a perception of benefit. The most popular forms of CAM were massage, herbal, chiropractic medicine, and acupuncture. The majority of respondents sought out CAM therapies without a recommendation by their medical provider. Slightly more than half had not discussed the use of CAM with their primary provider. Respondents felt that CAM should be offered in Navy MTFs and were willing to use or potentially use acupuncture as therapy in the ED. Further studies are necessary to determine the appropriate indications, efficacy, and patient satisfaction with acupuncture and other CAM therapies in the emergent setting.

References:

NCCAM

Facts-at-a-Glance and Mission. Available at

http://nccam.nih.gov/about/ataglance;

accessed July 19, 2012.Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What's in a Name?

Available at http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam;

accessed July 19, 2012.Barnes PM , Powell-Griner E , McFann K , Nahin RL:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults:

United States, 2002

Advance Data 2004 (May 27); 343: 119Barnes PM , Bloom B , Nahin RL:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children:

United States, 2007

US Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2008.McPherson F, Schwenka MA

Use of complementary and alternative therapies among active duty soldiers, military retirees,

and family members at a military hospital.

Mil Med 2004; 169(5): 3547.Rolniak S, Browning L, Macleod BA, Cockley P

Complementary and alternative medicine use among urban ED patients: prevalence and patterns.

J Emerg Nurs 2004; 30(4): 31824.Acupuncture Makes Strides in Treatment of Brain Injuries, PTSD. Available at

http://science.dodlive.mil/2011/06/20/acupuncture-makes-strides-in-treatment-of-brain-

injuries-ptsd-video/

accessed November 12, 2013.Sniezek DP

Guest Editorial: Community-based Wounded Warrior Sustainability Initiative (CBWSI):

an integrative medicine strategy for mitigating the effects of PTSD.

J Rehabil Res Dev 2012; 49(3): ixxix.Williams JW, Gierisch JM, McDuffie J, Strauss JL, Nagi A

An Overview of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies for Anxiety and Depressive Disorders:

Supplement to Efficacy of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies for Posttraumatic

Stress Disorder [Internet].

Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011 August. Available at

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22238805

accessed September 11, 2014.Koffman RL

Downrange acupuncture.

Medl Acupunct 2011; 23(4): 2158.Kent JB, Oh RC.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Military Family Medicine Patients in Hawaii

Military Medicine 2010 (Jul); 175 (7): 534538Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, et al.

A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and

alternative medicine: implications for integrated care.

Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(15): 1697704.Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among US Navy and Marine Corps Personnel

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007 (May 16); 7: 16White MR, Jacobson IG, Smith B, et al.

Health care utilization among complementary and alternative medicine users in a large military cohort.

BMC Complement Altern Med 2011; 11: 27.Li JZ, Quinn JV, McCulloch ED, Jacobs BP, Chan PV

Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use in ED patients and its association

with health care utilization.

Am J Emerg Med 2004; 22(3): 18791.Allen R, Cushman LF, Morris S, et al.

Use of complementary and alternative medicine among Dominican emergency department patients.

Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18(1): 514.Losier A, Taylor B, Fernandez CV

Use of alternative therapies by patients presenting to a pediatric emergency department.

J Emerg Med 2005; 28(3): 26771.Weiss SJ, Takakuwa KM, Ernst AA

Use, understanding, and beliefs about complementary and alternative medicines among

emergency department patients.

Acad Emerg Med 2001; 8(1): 417.Sawni A, Ragothaman R, Thomas RL, Mahajan P

The use of complementary/alternative therapies among children attending an urban pediatric

emergency department.

Clin Pediatrics 2007; 46(1): 3641.Gulla J, Singer AJ

Use of alternative therapies among emergency department patients.

Ann Emerg Med 2000; 35(3): 2268.Taylor DM, Walsham N, Taylor SE, Wong L

Use and toxicity of complementary and alternative medicines among emergency department patients.

Emerg Med 2004; 16(56): 4006.Kaptchuk TJ

Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice.

Ann Intern Med 2002; 136(5): 37483.Alimi D, Rubino C, Pichard-Leandri E, et al.

Analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture for cancer pain: a randomized, blinded, controlled trial.

J Clin Oncology 2003; 21(22): 41206.Ernst E, Pittler MH

The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating acute dental pain: a systematic review.

Br Dent J 1998; 184(9): 4437.Ezzo J, Hadhazy V, Birch S, et al.

Acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review.

Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44(4): 81925.Berman BM, Ezzo J, Hadhazy V, et al.

Is acupuncture effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia?

J Fam Practice 1999; 48(3): 2138.Skilnand E, Fossen D, Heiberg E

Acupuncture in the management of pain in labor.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002; 81(10): 9438.Ernst E, White AR, Wider B

Acupuncture for back pain: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and an update

with data from the most recent studies.

Schmerz 2002; 16(2): 12939[in German].Leibing E, Leonhardt U, Koster G, et al.

Acupuncture treatment of chronic low-back pain: a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial

with 9-month follow-up.

Pain 2002; 96(12): 18996.White AR, Ernst E

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for neck pain.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999; 38(2): 1437.Goertz C, Niemtzow R, Burns S, et al.

Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of acute pain syndromes: a pilot study.

Mil Med 2006; 171(10): 10104.Grout M

Medical acupuncture in the emergency department.

Med Acupunct 2002; 14(1): 3940.Zhang T, Smit D, Taylor D, Parker S, Xue C P02.195.

Acupuncture for acute pain management in an emergency department: an observational study.

BMC Complement Altern Med 201212(Suppl 1): P251.Arnold AA, Ross BE, Silka PA

Efficacy and feasibility of acupuncture for patients in the ED with acute,

nonpenetrating musculoskeletal injury of the extremities.

Am J Emerg Med 2009; 27(3): 2804.

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 3-24-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |