Chiropractic Services in the Canadian Armed Forces:

A Pilot ProjectThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Military Medicine 2006 (Jun); 171 (6): 572–576 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Luke A. Boudreau, BSc DC; Jason W. Busse, DC MSc PhD (Cand.); Graeme McBride, BSc DC

173 Waterloo Avenue,

Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

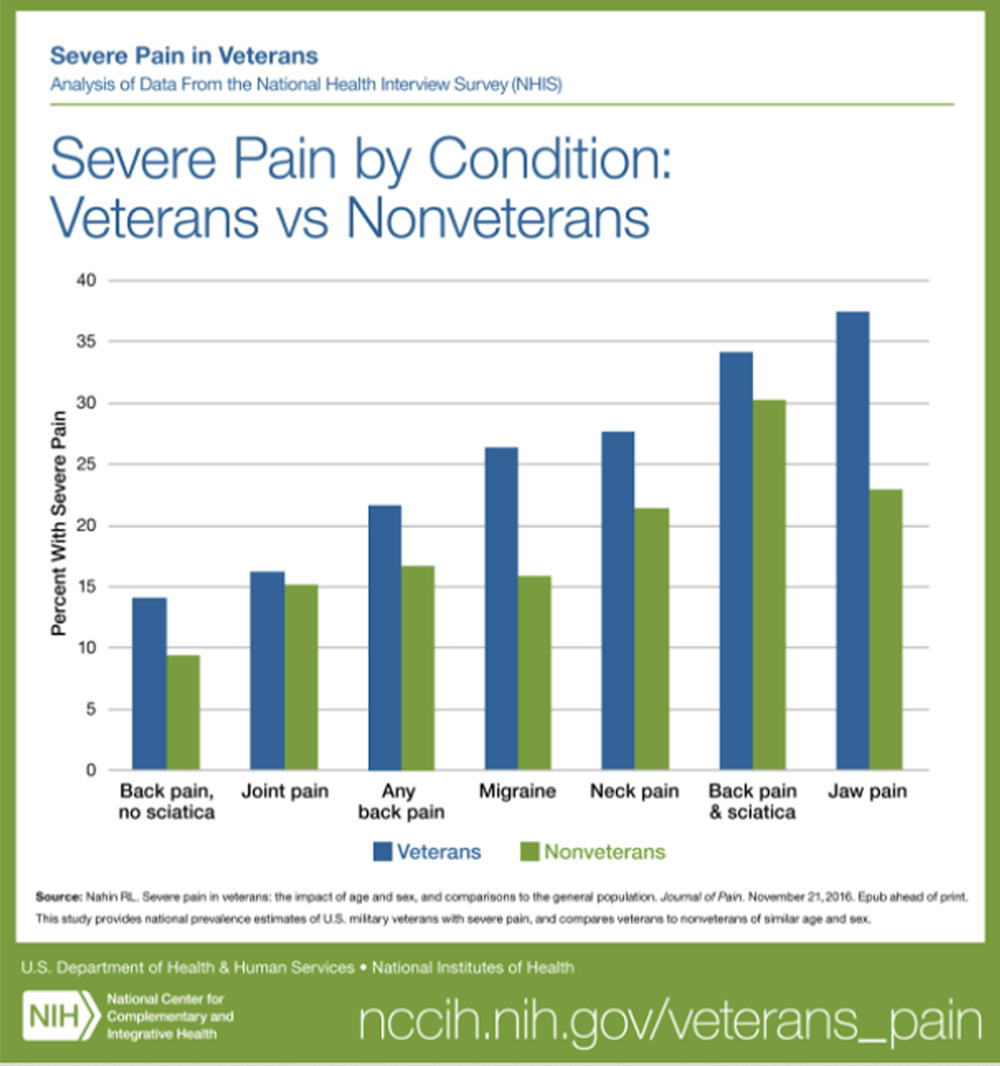

FROM: Nahin ~ Pain 2017

This article reviews results of surveys of 102 military personnel referred for chiropractic services in a Canadian Armed Forces Pilot Project. Traditionally, Canadian forces have had to self-pay for chiropractic services outside of the military system. The military personnel were all referred by the medical staff for chiropractic services. 52% of the patients complained of low back pain and their average initial onset was over 6 years. 94% of the patients responded that they were satisfied with the chiropractic care received while 80% of the referring physicians expressed satisfaction.

This article reports on satisfaction associated with the introduction of chiropractic services within a military hospital, through a Canadian Armed Forces Pilot Project. We distributed a 27-item survey that inquired about demographic information and satisfaction with chiropractic services to 102 military personnel presenting for on-site chiropractic services at the Archie McCallum Hospital in Halifax, Nova Scotia. We provided a second 3-item survey, designed to explore referral patterns and satisfaction with chiropractic services, to all referring military physicians. A multivariable linear regression model was constructed to explore which factors were associated with patients’ satisfaction with chiropractic services. The response rate to the patient and physician satisfaction surveys was 67.6% (69 of 102) and 83.3% (10 of 12), respectively. Chronic low back pain accounted for most presentations to the hospital chiropractic clinic. The majority of military personnel (94.2%) and referring physicians (80.0%) expressed satisfaction with chiropractic services. Our adjusted analysis found that older age (β = –0.37; 95% confidence interval = α0.73 to α0.02) and a presenting complaint of knee pain (= α15.56; 95% confidence interval = α29.61 to α1.51) was associated with decreased satisfaction with chiropractic care. Although our finding of high satisfaction with chiropractic services is encouraging, formal studies on functional outcomes and cost effectiveness of chiropractic care are required to better inform the role

There is more like this at our

CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS Page

From the FULL TEXT :

Introduction

Musculoskeletal complaints have been identified as a substantial source of morbidity among military personnel, leading to high attrition rates and retraining costs.1 Back pain and overuse injuries are major contributors to this problem. [1, 2] In 1993, the U.S. Congress passed a bill authorizing the Department of Defense to commission chiropractors, which led to a pilot project at 10 military hospitals3 that progressed to full integration of chiropractic practices into the American military health care system in 2001. [4]

Canadian Forces members have traditionally accessed chiropractic services outside the military system and have been paying out-of-pocket in many cases for these services. Recently, the Canadian military introduced chiropractic services into its spectrum of care in the form of a pilot project in one of its largest military hospitals. This study reports the findings of a survey of armed forces members attending the Archie McCallum Hospital at Canadian Forces Base Stadacona, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, which was designed to investigate patient demographics and satisfaction with chiropractic services.

Methods

On July 5, 2000, a 6-month trial of on-site chiropractic services was initiated through the outpatient department of the Archie McCallum Hospital at the Canadian Forces Base Stadacona in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Two chiropractors (G.M. and L.A.B.) were contracted to provide all chiropractic treatment.

Chiropractic services were restricted to the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders and referral from either a general practitioner or a medical specialist was required to access these services. Chiropractors were expected to provide the referring physician with an initial report for the medical file, including examination findings, clinical impressions, treatment plan and prognosis. Progress updates were also expected after 10 treatments on any particular case for further approval of care. Chiropractors were free to employ any treatment they deemed appropriate (within their scope of practice) and were encouraged to work with other hospital departments on shared patients.

Chiropractic scope of practice for the purpose of the trial included joint manipulation of the spine and extremities, soft tissue massage, stretches, and instruction on home exercise. Interferential current and acupuncture were also used as an adjunct therapy in some instances. Direct access to diagnostic imaging in the hospital was limited to x-rays, with medical referral required for computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging studies or any other diagnostic tests.

Patient Satisfaction Survey

For a 6-week period, beginning on September 1, 2000, each military personnel presenting for chiropractic services to the outpatient department of Archie McCallum Hospital was asked by the attending chiropractor to complete a 27-item survey. Patients were informed that the purpose of the survey was to collect data on perception of chiropractic services. Patients were also informed that their submissions would be anonymous and they were under no obligation to complete the survey. For those who consented, a survey was provided and they were asked to return the completed survey to the outpatient department front desk personnel within the week.

The timing of the survey was relatively early in the trial (approximately 2 months after initiation); however, sufficient time was needed for data collection and processing for a 6-month review of the project required by Formation Health Services at Canadian Forces Base Stadacona. A report on the pilot was then sent to National Defense Headquarters in Ottawa, Canada for further evaluation.

The 27-item satisfaction questionnaire used for this study was adapted from the chiropractic satisfaction survey by Sawyer and Kassek5 and was approved by Formation Health Services. The questions in the survey addressed several dimensions of patient care and environment (Table I). Any questions dealing with financial aspects of care were omitted, as members of the Canadian Forces are not required to pay out-of-pocket for health care provided on-site. The word “doctor” was also changed to “chiropractor” to prevent any confusion, as patients were often under concurrent medical care. Each question was accompanied by a 5-point Likert scale with response options from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The total score of the questionnaire was calculated by adding up the individual scores (1–5) for each of the 27-questions and could therefore range from 27 (lowest satisfaction) to 135 (highest satisfaction). For the purposes of analyses, response options were collapsed into “agree,” “unsure,” or “disagree.” Respondents were also provided with space to include additional written comments.

Patient Demographics

We reviewed the clinical files of all patients who completed a survey, and abstracted the following information: (1) gender, (2) presenting complaint, (3) initial time of onset of presenting complaint, (4) duration of presenting episode, and (5) total number of visits to the on-site chiropractic clinic. For the purpose of this study, acute was considered any complaint with duration of 3 months or less on presentation, subacute was considered between 3 and 6 months, and chronic was ≤6 months.

Physician Feedback Survey

We distributed an additional survey to gather physicians’ impressions concerning chiropractic services offered at the hospital outpatient clinic. The questionnaire was adapted from Verhoef [6] and was administered to all 12 referring physicians, approximately 1 month before the end of the 6-month trial. The survey consisted of three items, which queried perceived patient demand for chiropractic care, physician’s reasons for referral to chiropractic treatment (asked to list their top three reasons), and physician satisfaction with chiropractic services.

Analysis

Cronbach's α coefficient was used to determine the internal consistency of the survey. We generated frequencies for all collected data and created a linear regression model to assess the relation of the independent variables to the total score on the patient satisfaction questionnaire. Briefly, we tested each of the independent variables in univariable regression models for significance, and any variable that resulted in a p ≤ 0.10 was entered into a multivariable regression model. For the purpose of the multivariable regression model, significance was considered at p ≤ 0.05. All data were analyzed using the SPSS Advanced Statistics software package (version 10.0.5, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

The response rate for the patient survey was 67.6% (69 of 102). Cronbach’s α coefficient (internal consistency), for all 69 respondents, was 0.91. The first item on the survey asked about the respondent’s general satisfaction with chiropractic care. The Spearman correlation coefficient between responses to that question and the total score on the questionnaire (excluding that question) was 0.65 (p < 0.001), which provides preliminary evidence of the construct validity of the questionnaire. For the survey administered to the referring physicians, the response rate was 83.3% (10 of 12).

Most patients were male at a mean age of 36.9 ± 8.0 years. Axial complaints accounted for the majority of presentations (96.6%), the majority of which were low back pain (51.7%), with only 3.4% of complaints involving extremities (Table I). The initial onset of respondent’s presenting complaint was typically substantial, averaging over 6 years. Of the 61 respondents who provided data on the duration of their current episode, 41% were acute on presentation, 3.3% were subacute, and the majority of complaints were chronic (55.7%). The average number of total chiropractic treatments per respondent was 5.7 ± 4.1.

The large majority of respondents (94.2%) were satisfied with their chiropractic care, with none reporting being dissatisfied. Respondents were 100% in agreement that the office was easy to get to and that the attending chiropractor treated them with respect and concern. A large percentage of respondents (97.1%) agreed that their chiropractor thought that they were important and was careful to check everything during the examination. Other areas of high satisfaction included the clinic hours of operation (98.5%), which was from 7:00 a.m.to late afternoon (based on demand), and the chiropractor’s ability to answer patient questions (98.6%). Some respondents (37.6%) either disagreed that, or were unsure if, their chiropractor’s office had the appropriate equipment to provide good care (Table II). Comments provided in the survey indicated, in each of these cases, noted criticism of the medical treatment tables provided by the hospital and many respondents suggested that proper chiropractic tables were needed. Some respondents indicated that they expected better results from treatment or were unsure if they should have expected better results (30.3%), and 33.2% relayed that improvements took longer than expected or that they were unsure if their time to improvement was too long (Table II).

Our univariable linear regression models revealed three factors that were significantly associated with respondents’ satisfaction with chiropractic care (Table III). All significant variables were entered into a multivariable regression model, with the backward conditional model of variable entry. In this adjusted analysis, only older age (β = –0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI] = –0.73 to –0.02) and a presenting complaint of knee pain (β = –15.56; 95% CI = –29.61 to –1.51) remained significantly associated with lower satisfaction with chiropractic care (Table III).

With regard to the survey completed by referring physicians, all respondents perceived a demand from patients for chiropractic services. The majority were satisfied with chiropractic services provided (80.0%), with two respondents reporting being unsure as they had not been involved with the pilot project long enough to provide comment. The remaining 10 physicians each indicated their three main reasons for referring to chiropractic services, which were aggregated into five distinct categories. The majority of respondents indicated they referred to chiropractic services for predominantly axial, musculoskeletal complaints (8 of 10), with other reasons being the complaint was unresponsive to physiotherapy (2 of 10), specific patient request (2 of 10), waiting list was too long for physiotherapy (1 of 10), and previous patient history of positive response to chiropractic care (1 of 10).

Discussion

Our surveys found a high rate of satisfaction with use of chiropractic services in a Canadian military hospital setting for both patients (94.2%) and referring medical physicians (80.0%). All patient respondents agreed that the location of the chiropractic clinic was easy to get to, suggesting that a hospitalbased clinic was favorable. Patients also felt they were treated with respect and concern by their attending chiropractor and were highly satisfied with the clinic hours of operation and the ability of the chiropractors to answer questions. Lower satisfaction among patients was associated with older age and presenting with a knee complaint. Despite a high rate of satisfaction with care among patients, one-third of respondents indicated that they expected better results, were unsure whether they should have expected better results, and relayed that improvements took longer than expected, or were unsure whether improvements had taken too long.

In a Swedish study of 30 chiropractors and 336 patients, Sigrell [7] found that chiropractors and patients had many similar goals concerning care, but patients had lower expectations of chiropractic treatment than the chiropractors and greater expectations of being given advice and exercises. There was also a trend that patients expected to get better faster than the chiropractors expected them to. Sigrell did not explore whether fulfillment of expectations impacts on patient satisfaction. [7]

In general, low back pain patients tend to be more satisfied with chiropractic care as compared to other heath providers; [8, 9] however, clinical outcomes appear to be similar among different health care providers and Carey et al [9] have speculated that the patient-chiropractor relationship may be responsible for higher satisfaction. Health attitudes and beliefs of chiropractors and their patients tend to be similar [10] and a number of recent studies have established that treatment by a chiropractor can provide substantial nonspecific benefit and that communication of advice and information to patients accounts for much of the difference between chiropractic and medical patients’ satisfaction. [11–13]

Scarcity of resources is an accepted reality in health care, and in addition to patient satisfaction there is a need to consider both clinical outcomes and economic factors when evaluating treatment options. Cost-effectiveness studies of chiropractic care compared to other musculoskeletal care providers have focused on low back pain, and results have been conflicting. [9, 14–18] A recent systematic review that included nine studies was unable to establish the cost-effectiveness of chiropractic treatment for low back pain versus medical care, and several methodological limitations of reviewed trials were noted. [19] A more recent systematic review concluded that chiropractic management did not lead to a reduction of costs related to back pain when compared to physiotherapy or an educational booklet; however, this conclusion was based solely on the results of 644 patients included in two randomized trials. [20] The largest study done to date that explored the cost-effectiveness of chiropractic care was a 4-year retrospective claims data analysis of more than 1 million members of a health care plan, comparing health care expenditures between those with and those without chiropractic coverage. [21] Access to chiropractic care was significantly correlated with a reduction in the cost of caring for neuromuscular complaints and back pain and was associated with lower utilization of radiography, magnetic resonance imaging, back surgery, and hospitalization.

As far as we are aware, ours is the first study to explore the implementation of chiropractic services in a Canadian military hospital setting. Our findings are limited by our modest sample size. Although surveys were anonymous and left with front desk staff upon completion, we cannot exclude the possibility that some respondents may have felt pressure to provide more favorable ratings of their chiropractic care. Furthermore, the high satisfaction scores in our patient survey present challenges to our linear regression model, as marginal variation in this data provided limited opportunity to establish associations between variables. We did not collect data on functional outcomes or costs, and the practical implications of our high patient satisfaction rates are not known.

Despite these initially encouraging results, a number of important questions remain to be answered. It is not known whether provision of chiropractic services to Canadian military personnel promotes advantages in functional recovery from musculoskeletal complaints, or what impact the addition of chiropractic might have on existing rehabilitation services. Research on cost-effectiveness and health outcomes should be conducted to further inform the role of chiropractors in the Canadian military.

Acknowledgments

Luke A. Boudreau was responsible for conception and implementation of the study design, collection of the data, and preparation and critical revision of the final manuscript. Jason W. Busse was responsible for design and implementation of the data analysis, interpretation of the data, and preparation and critical revision of the final manuscript. Graeme McBride was responsible for conception and implementation of the study design and critical revision of the final manuscript. No funds were received for the preparation of this manuscript. Jason W. Busse is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship Award.

References:

Kaufman KR, Brodine S, Shaffer R:

Military training-related injuries: surveillance, research, and prevention.

Am J Prev Med 2000; 18: 54–63.Visuri T:

Impact of chronic low back pain on military service.

Milit Med 2001; 166: 607–11.Lott CM:

Integration of chiropractic in the armed forces health care system.

Milit Med 1996; 161: 755–9.Lowe DT:

The military and chiropractic: answers to FAQ.

Dynamic Chiro 2004; 22: 15.Sawyer CE, Kassek K:

Patient Satisfaction With Chiropractic Care

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1993 (Jan); 16 (1): 25–32Verhoef MJ, Page SA:

Physicians’ Perspectives on Chiropractic Treatment

J Can Chiro Assoc 1996 (Dec); 40 (4): 214–219Sigrell H.

Expectations of Chiropractic Treatment: What Are the Expectations of New Patients Consulting

a Chiropractor, and Do Chiropractors and Patients Have Similar Expectations?

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002 (Jun); 25 (5): 300–305Cherkin, D.C. and MacCornack, F.A.

Patient Evaluations of Low Back Pain Care From

Family Physicians and Chiropractors

Western Journal of Medicine 1989 (Mar); 150 (3): 351–355Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, et al.

The Outcomes and Costs of Care for Acute Low Back Pain Among Patients

Seen by Primary Care Practitioners, Chiropractors, and Orthopedic Surgeons

New England J Medicine 1995 (Oct 5); 333 (14): 913–917Coulter ID, Hurwitz EL, Adams AA, Genovese BJ, Hays R, Shekelle PG.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002; 27 (3) Feb 1: 291–298Meeker, W., & Haldeman, S. (2002).

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216–227Hertzman-Miller RP, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, et al.

Comparing the Satisfaction of Low Back Pain Patients Randomized to Receive Medical or Chiropractic Care:

Results From the UCLA Low-back Pain Study

Am J Public Health 2002 (Oct); 92 (10): 1628–1633Breen A, Breen R.

Back Pain and Satisfaction with Chiropractic Treatment: What Role Does the Physical Outcome Play?

The Clinical Journal of Pain 2003 (Jul); 19 (4): 263–268Stano M, Smith M:

Chiropractic and Medical Costs of Low Back Care

Medical Care 1996 (Mar); 34 (3): 191–204Skargren EI, Carlsson PG, Oberg BE:

One-year follow-up comparison of the cost and effectiveness of chiropractic and physiotherapy as primary

management for back pain: subgroup analysis, recurrence, and additional health care utilization.

Spine 1998; 23: 1875–83.Stano M, Haas M, Goldberg B, Traub PM, Nyiendo J:

Chiropractic and medical care costs of low back care: results from a practice-based observational study.

Am J Manag Care 2002; 8: 802–9.Kominski GF, Heslin KC, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, Harber PI:

Economic evaluation of four treatments for low-back pain: results from a randomized controlled trial.

Med Care 2005; 43: 428–35.Shekelle PG, Markovich M, Louie R:

Comparing the Costs Between Provider Types of Episodes of Back Pain Care

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995 (Jan 15); 20 (2): 221–227Baldwin ML, Cote P, Frank JW, Johnson WG:

Cost effectiveness studies of medical and chiropractic care for occupational low back pain:

a critical review of the literature.

Spine J 2001; 1: 138–47.Cherkin, DC, Sherman, KJ, Deyo, RA, and Shekelle, PG.

A Review of the Evidence for the Effectiveness, Safety, and Cost of Acupuncture,

Massage Therapy, and Spinal Manipulation for Back Pain

Annals of Internal Medicine 2003; 138: 898–906Legorreta, AP, Metz, RD, Nelson, CF, Ray, S, Chernicoff, HO, and Dinubile, NA.

Comparative Analysis of Individuals With and Without Chiropractic Coverage:

Patient Characteristics, Utilization, and Costs

Archives of Internal Medicine 2004 (Oct 11); 164 (18): 1985–1892

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 9-20-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |