Complementary and Integrated Health Approaches:

What Do Veterans Use and WantThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Gen Intern Med. 2019 (Jul); 34 (7): 1192–1199 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Stephanie L. Taylor, PhD, Katherine J. Hoggatt, MPH, and Benjamin Kligler, MD, MPH

Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation,

Implementation and Policy,

Greater Los Angeles VA Healthcare System,

Los Angeles, CA, USA.

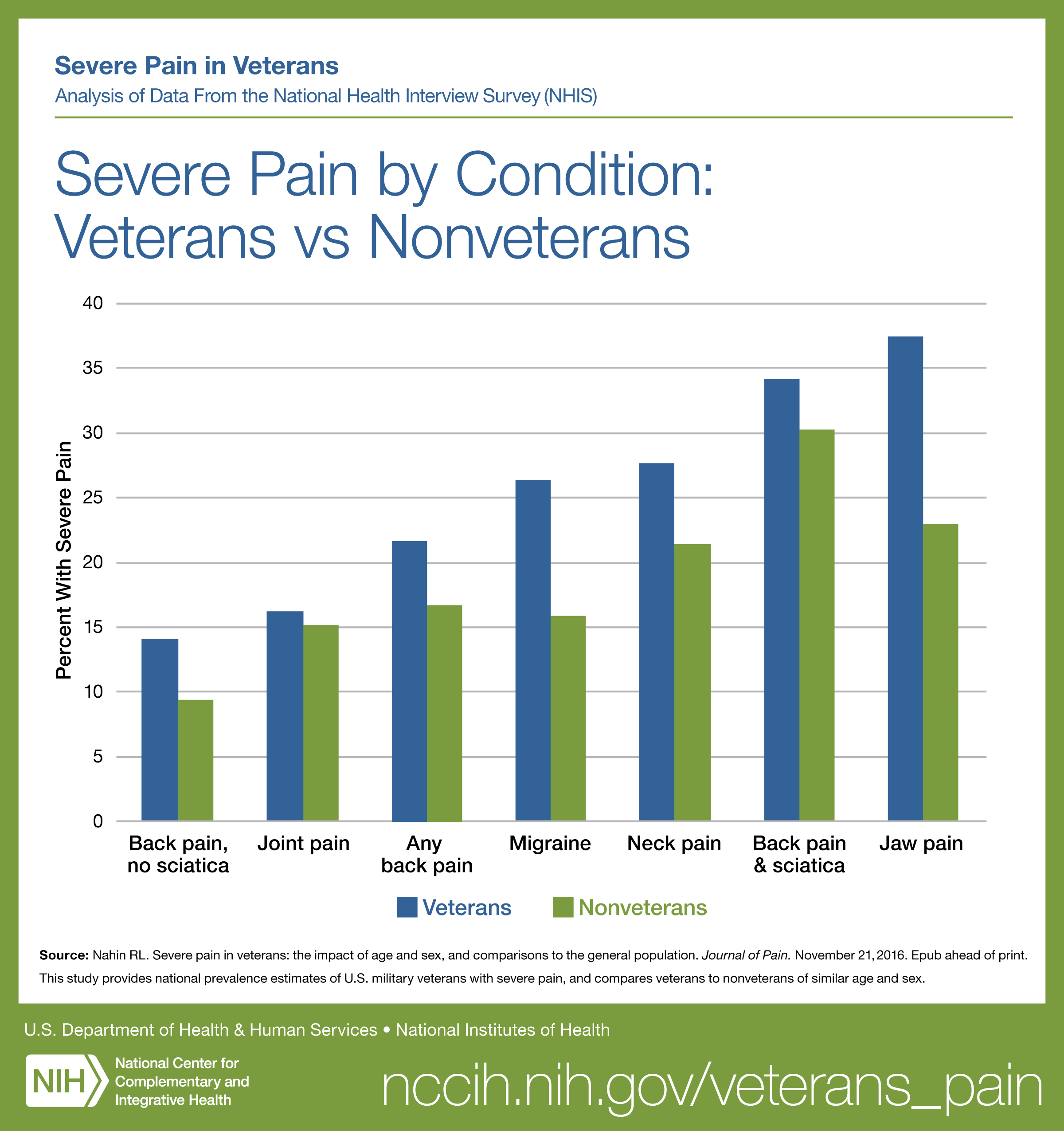

FROM: Nahin ~ Pain 2017OBJECTIVES: Non-pharmacological treatment options for common conditions such as chronic pain, anxiety, and depression are being given increased consideration in healthcare, especially given the recent emphasis to address the opioid crisis. One set of non-pharmacological treatment options are evidence-based complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, such as yoga, acupuncture, and meditation. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the nation's largest healthcare system, has been at the forefront of implementing CIH approaches, given their patients' high prevalence of pain, anxiety, and depression. We aimed to conduct the first national survey of veterans' interest in and use of CIH approaches.

METHODS: Using a large national convenience sample of veterans who regularly use the VHA, we conducted the first national survey of veterans' interest in, frequency of and reasons for use of, and satisfaction with 26 CIH approaches (n?=?3346, 37% response rate) in July 2017.

RESULTS: In the past year, 52% used any CIH approach, with 44% using massage therapy, 37% using chiropractic, 34% using mindfulness, 24% using other meditation, and 25% using yoga. For nine CIH approaches, pain and stress reduction/relaxation were the two most frequent reasons veterans gave for using them. Overall, 84% said they were interested in trying/learning more about at least one CIH approach, with about half being interested in six individual CIH approaches (e.g., massage therapy, chiropractic, acupuncture, acupressure, reflexology, and progressive relaxation). Veterans appeared to be much more likely to use each CIH approach outside the VHA vs. within the VHA.

There is more like this at our

CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS PageCONCLUSIONS: Veterans report relatively high past-year use of CIH approaches and many more report interest in CIH approaches. To address this gap between patients' level of interest in and use of CIH approaches, primary care providers might want to discuss evidence-based CIH options to their patients for relevant health conditions, given most CIH approaches are safe.

KEYWORDS: alternative medicine; chronic pain; complementary and alternative medicine; veterans

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Non-pharmacological treatment options for common conditions such as chronic pain, anxiety, and depression are being given increased consideration in healthcare. For example, in part to address the opioid epidemic, the Department of Health and Human Services’ National Pain Strategy [1] and the American College of Physicians’ low back pain clinical practice guidelines [2] recommend complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, such as tai chi, yoga, and acupuncture among the suggested non-pharmacological treatment options.

These recommendations are based largely on the evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CIH approaches. For example, NIH researchers’ review of RCTs found evidence supporting the effect of several CIH approaches on several types of pain, [3] with similar results found in other reviews of systematic reviews. [4–11] Recent RCTs of mindfulness approaches show they appear to improve chronic low back pain, [12, 13] and mindfulness and yoga may help with depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. [14, 15] The National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) [16] and others report that patients often prefer to use CIH approaches because they prefer nonpharmacological self-management options, experienced unwanted side effects, or had limited response to pharmacologic and other common treatments. [17, 18]

Given the evidence, a desire to satisfy patient demand for non-pharmacological treatment options, and the potential to reduce healthcare costs, [19] some healthcare systems have increasingly been making CIH approaches available. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is being implemented throughout the UK’s National Health Service [20]; almost half of American Hospital Association-affiliated hospitals offered CIH therapies in 2010 [21]; and 93% of facilities in the nation’s largest integrated healthcare system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), offered CIH in 2011. [22] Currently, the VHA is undergoing a significant expansion in the provision of evidence-based CIH approaches to fulfill the requirements of the 2016 Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA) legislation. [23] According to a new policy directive as of May 2017, the VHA considers the following evidencebased CIH approaches as part of the standard medical benefits package: acupuncture, therapeutic massage, guided imagery, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, tai chi, yoga, and meditation. Chiropractic has been part of standard VHA care since 2005

In part to guide this expansion of evidence-based CIH, VHA leaders sought current information on veterans’ interest in and use of various CIH approaches, both inside and outside the VHA system because existing surveys of veterans’ use of CIH approaches use very small or old samples. [24, 25] Veterans represent 7% of the population and are similar to the Medicaid population in that they tend to have less income and education, are predominately male, and are more disabled than the general population. [26] Veterans have high need for management of chronic pain and symptoms of anxiety or depression, [27–29] conditions for which some types of CIH might be effective.

This paper presents the results of a survey of a large sample of veterans on their interest in, use of, and satisfaction with 26 CIH approaches. The results are being used not only to guide national VHA policy and operations supporting CIH delivery but also to inform other healthcare systems as they decide which CIH approaches to offer patients among their non-pharmacological treatment options to improve patient health and satisfaction. Knowing which types of treatments patients prefer, especially for prevalent conditions like pain and stress, is a key issue for most healthcare organizations, not only the VA. Patient satisfaction matters more than ever because many healthcare systems need to report on patient satisfaction for reimbursement issues or need to respond to patient advocacy groups and councils.

METHODS

Overview. A total of 3364 members of the national VHA’s Veteran Insights Panel (VIP) were invited via email to participate in the survey fielded July 17–25, 2017, with 1,230 completing the survey. The survey was designed in consultation with the VHA office overseeing CIH policy, the Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation, and the VIP sponsor, the VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients Program (SHEP) under the Office of Reporting, Analytics, Performance, Improvement and Deployment (RAPID). This survey received IRB approval as an operations project.

Veteran Insights Panel. The VIP is a national online group of veterans who regularly use VA care and is organized to enable veterans to provide feedback on VA programs and services. Panel members originally were identified from a sample extracted from the VHA database and were contacted via a recruitment email. The panel is periodically refreshed, purging panelists with a history of non-participation and recruiting new panelists. Panel members are not incentivized or compensated monetarily for their participation on the VIP. For their participation in this survey, VIP members were given a survey link and asked to complete it within 2 weeks. To describe the full VIP (N = 3,364) to potential VHA users, the panel are periodically surveyed on four descriptive characteristics (although data from this descriptive survey is unavailable to be linked with individual surveys such as ours). In July 2017, the full VIP panel reported the following: (1) their health status as very good or excellent (32%), good (38%), or poor (31%); (2) their residence as urban (63%) or rural (37%); and (3) their length of time of using the VA as:10 or more years (39%), 5–9 years (26%), 1–4 years (29%), less than 1 year (2%), and do not use (4%) (although the VA attempts to survey only VA users, a very small percent actually did not use the VA). Lastly, they reported their level of VHA utilization as at least once/month (28%) or every few months or less (68%), with the 4% who were non-users not responding to this question.

Variables. We assessed veterans’ use of and interest in 26 CIH approaches by providing brief descriptions for each (shown in Table 3) and asking about the following:(1) frequency of pastyear use;

(2) reasons for use (e.g., pain, stress/relaxation, sleep, post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD), or other);

(3) how helpful it was for addressing the endorsed reasons;

(4) veterans’ knowledge of CIH approaches being offered at their VA medical center;

(5) whether it was used in or outside a VA setting or both;

(6) reasons for using it outside the VA;

(7) interest in trying or learning more about it; and

(8) reasons if any for not being interested in trying or learning more about it.The 26 approaches were those we were aware of being provided at some VA medical centers, although the evidence base for some are stronger than for others. We also created a summary variable for any use of CIH (used at least one vs. no use). To improve access to care, the VA has recently started contracting with community-based providers to deliver some care (including acupuncture and chiropractic care). Our item asking whether respondents used care within or outside the VA setting was intentionally not designed to discern if the care was paid for by the VA or not. For policy reasons, we cared less about who provided the care and more about whether care was used within the VA medical setting or in the community.

Analysis. We first computed descriptive statistics for patients who reported any use of CIH vs. no use of CIH. We then fit a multiple-variable logistic regression model of any CIH use on age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and income, with all terms entered simultaneously (categories for all predictors are shown in Table 2). Using the fitted model, we computed adjusted odds ratios (point and 95% confidence interval estimates) to estimate the associations between patients’ demographic characteristics and any use of CIH. We then determined, for each CIH approach, the most frequently reported reason for using that CIH approach and the setting of CIH use in the past year (the proportion reporting BVA, “Somewhere else,” or “Both”).

Reasons for using CIH approaches were summarized by first determining, for each CIH approach, the reasons participants reported for using that approach. We then computed the proportion of VIP members who endorsed the most frequently reported reason for using that CIH approach.

We also summarized frequency of use for each CIH approach as the proportion of veterans endorsing each frequency option (no use, a few times a year, a few times a month/about once a month, and almost every day/a few times a week).

We assessed the helpfulness of each CIH approach for the most frequently reported reason for using that CIH approach by computing the proportion of VIP members who reported the approach was “Very” or “Moderately” helpful.

Finally, interest in trying or learning more about each CIH approach was summarized as the proportion in each interest category (interest in learning more at the local VA, interest in trying the approach at the local VA, interest in trying the approach in the Veteran’s neighborhood, or no interest in the approach). Analyses were conducted using R (version 3.2.2).

RESULTS

Almost two-thirds (63%) of the veteran survey respondents were married, 8% were single, and 29% were separated, divorced, or widowed. A majority (86%) were Non-Hispanic White, while 6% were Hispanic, 7% were Non-Hispanic Black, 2% were Asian, and 5% were Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander or American Indian/Native American. About half (56%) reported an annual income of less than $60,000, and 11% reported an annual income of $100,000 or greater.

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4 In the past year, almost half (52%) used any type of CIH approach. Table 1 presents the descriptions of CIH users and non-users, and presents use within and outside the VA. It shows that patients who used CIH approaches were more likely to be under age 65, female, and have higher incomes than patients not using CIH approaches.

Table 2 presents the adjusted associations between predictors of any CIH use vs. no CIH use. It shows users were more likely to be middle-aged, women, and non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander or American Indian/Native American, and users were less likely to have annual incomes of $10,000 or less or to be non-Hispanic Black.

Table 3 presents past-year utilization of CIH approaches by setting of use (within the VA setting, outside the VA setting, both within and outside the VA, and total). Massage therapy was the most frequently used CIH approach in the past year, with 44% using it, followed by 37% using chiropractic and 34% using mindfulness. Except for Battlefield acupuncture, which is not readily available outside of VA or military settings, veterans appeared to be much more likely to use each CIH approach outside the VA vs. within the VA.

When asked about the frequency of use, “at least weekly” use was reported by 8% for mindfulness and 7% for animal-assisted therapy, and “a few times amonth”/“about once a month” was reported by 12% for massage, 11% for chiropractic, and 6% for mindfulness.

The first column in Table 4 shows veterans’ most frequently reported reasons for using each CIH approach. For nine CIH approaches, pain and “stress reduction/relaxation” were the two most frequent reasons for using those approaches, followed by “improve overall health and well-being” for five CIH approaches and PTSD for one approach. The second column in Table 4 shows the percent of veterans reporting that that particular approach was “moderately helpful” or “very helpful” for the most frequently reported reason for its use. For example, 81.7% of people reported using acupressure for pain and over half of those (56.6%) said it was moderately or very helpful for pain.

It appears the most helpful approaches for pain were chiropractic and massage therapy, and the most helpful approaches for stress reduction/relaxation were “hypnotherapy/hypnosis” and animal-assisted therapy.

Table 5 Table 5 describes veterans’ interest in trying or learning more about each CIH approach among those not using each CIH approach in the past year. Overall, 84% said they would be interested in trying/learning more about at least one CIH approach. Of those 84%, 43% were veterans who had not used a CIH approach in the past year (not in the table). When considering each specific CIH approach, about half (45% or more) said they were interested in six individual CIH approaches (e.g., massage therapy, chiropractic, acupuncture, acupressure, reflexology, and progressive relaxation).

DISCUSSION

Our survey of a national convenience sample of veterans who regularly use VA care found that about half of participants had used any of the 26 CIH approaches in the past year. The most frequently used approaches were massage therapy, chiropractic, mindfulness or some other type of meditation, progressive relaxation, and yoga, with at least 20% or more of veterans using each of these. It is interesting that these most frequently used approaches appear somewhat split between passive, provider-delivered and active, self-care approaches. Additionally, about a third of veterans who had not used a particular type of CIH were interested in trying it or learning more about it, for all but one CIH approach (Battlefield Acupuncture). For six CIH approaches, these levels of interest were even higher, in some cases twice or more the percentage of veterans using most of the CIH approaches. Pain and stress reduction/ relaxation were the two most frequent reasons given for using CIH approaches, with improving overall health and well-being the third. Veterans reported for all but two types of CIH that it was moderately or very helpful for the reason for which they used it.

The prevalence of CIH utilization we found among veterans appears much higher than that reported for the general population in 2012. [30] This may reflect the shift of some CIH approaches (e.g., meditation and yoga) to becoming more mainstream in the last few years or it could reflect the fact that CIH approaches are typically being provided at no or relatively low cost to veterans using the VHA healthcare system. It also might be that veterans who were interested in CIH approaches were more likely than other veterans to complete the survey, meaning that the rates of use and interest among the wider veteran population could be lower. These self-reported utilization rates were higher than those found in our earlier examination of 2010–2013 medical record-reported utilization rates among VHA users having chronic musculoskeletal pain. [31] However, that examination used natural language processing to extract CIH utilization from medical records and most likely did not completely account for community-based CIH utilization as we do in this examination, so those estimates could be less reliable. Veterans’ CIH utilization will likely increase in the near future given the expansion of CIH provision as a non-pharmacological treatment for pain in the VHA mandated by Congress in the 2016 Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. [23]

The gap we found between veterans’ interest in CIH approaches and their use of CIH approaches might point to an opportunity for primary care providers to educate their patients about evidence-based CIH approaches for particular health conditions. There is a large amount of scientific evidence for some types of CIH approaches for some types of health conditions, while the evidence is nascent or nonexistent for many others. As such, it can be difficult for providers and patients to understand the array of potentially appropriate non-pharmacological treatment options. Our earlier research among veterans and their providers found patients are particularly responsive to CIH-based demonstrations, provider-delivered education, videos, and brief written materials. [32]

It is not surprising that pain is one of the two most frequently reported reasons for using CIH approaches, given the high prevalence of pain among veterans [33, 34] and the efforts among healthcare providers to offer non-opioid alternatives for pain management. [2] Half or more of veterans reported that acupressure, acupuncture, healing touch/reiki, chiropractic, massage therapy, movement therapy, and biofeedback helped their pain. The evidence for some of these is stronger than others. As such, it might be prudent to offer patients a variety of CIH treatment options shown to have evidence of effectiveness for their particular condition.

Our study has some limitations. First, our sample is not representative of the veteran population in general in that we used a large convenience sample. However, it is the first large examination of CIH use among veterans nationally. Second, the veteran patient population is not generalizable to the entire population, even when considering those of the same age, [26] and they may have incurred their health conditions through active duty situations that incur psychological as well as physical stress not experienced by the general population. Additionally, we achieved a 37% response rate, which is rather standard for patient surveys. However, as noted above, it likely resulted in overestimates of the use of and interest in CIH approaches. Also, due to survey length restrictions, we were unable to survey the VIP sample on four characteristics (length of time using the VHA, level of VHA utilization, health status, and urban/ rural residence) so we could not include these data in the analysis. We did receive this information for the full sample of 3,364 VIP members as a whole, but due to privacy restrictions could not link it with the survey responses. Also, fewer than 50 people reported using 7 of the 26 approaches we examined, which limited our ability to explore the correlates of these approaches.

Most CIH approaches are safe non-pharmacological strategies to improve health. We found that about half or more of veterans thought the CIH approach they used was helpful for a particular type of health condition. Given this, primary care providers might consider informing their patients about some CIH approaches as potential options to improve their health.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Alison Whitehead and Amanda Hull at the VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation; Mark Meterko at the VA SHEP Program under the Office of Reporting, Analytics, Performance, Improvement and Deployment (RAPID); and the IPSOS team for input on the survey content and executing the survey.

Funders

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative Program (PEC 16-354).

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References:

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health.

National Pain Strategy: A Comprehensive Population

Health-Level Strategy for Pain

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services,

National Institutes of Health; 2016.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Nahin RL, Boineau R, Khalsa PS, Stussman BJ, Weber WJ.

Evidence-Based Evaluation of Complementary Health Approaches for Pain Management in the United States

Mayo Clin Proc. 2016 (Sep); 91 (9): 1292–1306Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 493–505Paige NM, Myiake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al.

Association of Spinal Manipulative Therapy with Clinical Benefit and Harm

for Acute Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

JAMA. 2017 (Apr 11); 317 (14): 1451–1460Hempel, S., Taylor, S. L., Solloway, M., Miake-Lye, I. M., Beroes, J. M.

Evidence Map of Acupuncture

Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014 (Jan)Goode AP, Coeytaux RR, McDuffie J, Duan-Porter W, Sharma P.

An evidence map of yoga for low back pain.

Complement Ther Med 2016;25:170–7Solloway M, Taylor SL, Miake-Lye IM, Beroes JM, Shanman R.

An evidence map of the effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes.

Syst Rev 2016; 5(1):126.Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B.

Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Metaanalysis.

Ann Behav Med 2017;51(2):199–213.Hempel, S., Taylor, S. L., Marshall, N. J., Miake-Lye, I. M., Beroes, J. M.

Evidence Map of Mindfulness

Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2014 Oct.Miake-Lye IM, Lee JF, Luger T, Taylor S, Shanman R, Beroes JM, Shekelle PG.

Massage for Pain: An Evidence Map.

VA ESP Project #05-226; 2016.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Anderson ML, Hawkes RJ.

Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on

Back Pain and Functional Limitations in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA 2016 ;315(12):1240–9.Morone NE, Greco CM, Moore CG, Rollman BL, Lane B, Morrow LA, Glynn NW.

A Mind-Body Program for Older Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(3):329–37.Duan-Porter W, Coeytaux RR, McDuffie J, et al.

Evidence Map of Yoga for Depression, Anxiety and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder.

J Phys Act Health 2016;13(3):281–8.Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, Moran A, Lamberty, GJ, Collins RC.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: a randomized trial.

JAMA 2015;314(5): 456–465.Institute of Medicine (U.S.)

Complementary and alternative medicine in the United States/

Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public,

Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.

Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005.Barnes PM , Bloom B , Nahin RL:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children:

United States, 2007

US Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2008.Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Strouse TB, Bodenheimer BJ.

Contemporary, unorthodox treatment in cancer medicine: a study of patients, treatments and practitioners.

Ann Intern Med 1984; 101:105–112.Stahl JE, Dossett ML, LaJoie AS, Denninger JW, Mehta DH, Goldman R, et al.

Relaxation Response and Resiliency Training and Its Effect on Healthcare Resource Utilization.

PLoS One 2015. 10(10): e0140212.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140212Crane RS, Kuyken W.

The Implementation of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Learning From the UK Health Service Experience.

Mindfulness 2013;4:246–254.Ananth S.

2010 Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals.

Samueli Institute, Alexandria, VA. Available at:

http://www.samueliinstitute.org/File%20Library/Our%20Research/OHE/CAM_Survey_2010_oct6.pdfEzeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM.

State of Care: Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Veterans Health Administration–

2011 Survey Results.

Fed Pract 2013; 14–19.Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) of 2016.

TITLE IX–DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS. Subtitle C–Complementary and Integrative Health.

Section 931. Expansion of research and education on and delivery of complementary and integrative health to veterans.

Section 932. Expansion of research and education on and delivery of complementary and integrative health to veterans.

Section 933. Pilot program on integration of complementary and integrative health and related issues

for veterans and family members of veterans.Lozier CC, Nugent SM, Smith NX, Yarborough BJ, Dobscha SK, Deyo RA, Morasco BJ.

Correlates of Use and Perceived Effectiveness of Nonpharmacologic Strategies for

Chronic Pain Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioid Therapy.

JGIM; 2018, 33 (Supp.1): 46–53.Edmond SN, Becker WC, Driscoll MA, Decker SE, Higgins DM, Mattocks KM, et al.

Use of Non-Pharmacological Pain Treatment Modalities Among Veterans with Chronic Pain:

Results from a Cross-Sectional Survey

J Gen Intern Med. 2018 (May); 33 (Suppl 1): 54–60Wong ES, Wang V, Liu C-F, Hebert PL, Maciejewski ML.

Do Veterans Health Administration Enrollees Generalize to Other Populations?

Med Care Res Rev; 2015:1–15.Clark M, Bair MJ, Buckenmaier CI, Gironda R, Walker R.

Pain and OIF/OEF combat injuries: implications for research and practice.

J Rehabil Res Dev 2007;44:179–94.Lang KP, Veazey-Morris K, Andrasik F.

Exploring the Role of Insomnia in the Relation Between PTSD and Pain in Veterans with Polytrauma Injuries.

J Head Trauma Rehabil 2014;29(1):44–53.Clark ME, Walker RL, Gironda RJ, Scholten JD.

Comparison of pain and emotional symptoms in soldiers with polytrauma: unique aspects of blast exposure.

Pain Med 2009;10(3):447–55.National Center for Health Statistics

Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults:

United States, 2002-2012

National Health Statistics Report 2015 (Feb 10); (78): 1–16Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, Zeng Q, Yuan A, Chu K, Shou Y.

Use of Complementary and Integrated Health:

A Retrospective Analysis of by U.S. Veterans with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Nationally.

J Altern Complement Med 2018 Oct 12.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0276. [Epub ahead of print]Clark DJ.

Chronic Pain Prevalence and Analgesic Prescribing in a General Medical Population.

J Pain Symp Mgmt February 2002 Volume 23, Issue 2, Pages 131–137.Kerns RD, Dobscha SK.

Pain among veterans returning from deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan:

update on the Veterans Health Administration Pain Research Program.

Pain Med 2009;10(7):1161–4.Taylor SL, Giannitrapani K, Yuan A, Marshall N.

What Patients and Providers Want to Know About Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies.

J Altern Complement Med 2018. Jan;24(1):85–89.

Return to REHABILITATION DIPLOMATE

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 5-02-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |