Veteran Experiences Seeking

Non-pharmacologic Approaches for PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Military Medicine 2018 (Nov 1); 183 (11-12): e628-e634 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Karleen Giannitrapani, PhD, Matthew McCaa, BS, Marie Haverfield, PhD,

Robert D Kerns, PhD, Christine Timko, PhD, Steven Dobscha, MD, Karl Lorenz, MD

VA Palo Alto Health Care System,

Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i),

Menlo Park, CA.INTRODUCTION: Pain is a longstanding and growing concern among US military veterans. Although many individuals rely on medications, a growing body of literature supports the use of complementary non-pharmacologic approaches when treating pain. Our objective is to characterize veteran experiences with and barriers to accessing alternatives to medication (e.g., non-pharmacologic treatments or non-pharmacologic approaches) for pain in primary care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: Data for this qualitative analysis were collected as part of the Effective Screening for Pain (ESP) study (2012-2017), a national randomized controlled trial of pain screening and assessment methods. This study was approved by the Veterans Affairs (VA) Central IRB and veteran participants signed written informed consent. We recruited a convenience sample of US military veterans in four primary care clinics and conducted semi-structured interviews (25-65 min) elucidating veteran experiences with assessment and management of pain in VA Healthcare Systems. We completed interviews with 36 veterans, including 7 females and 29 males, from three VA health care systems. They ranged in age from 28 to 94 yr and had pain intensity ratings ranging from 0 to 9 on the "pain now" numeric rating scale at the time of the interviews. We analyzed interview transcripts using constant comparison and produced mutually agreed upon themes.

RESULTS: Veteran experiences with and barriers to accessing complementary non-pharmacologic approaches for pain clustered into five main themes: communication with provider about complementary approaches ("one of the best things the VA has ever given me was pain education and it was through my occupational therapist"), care coordination ("I have friends that go to small clinic in [area A] and I still see them down in [facility in area B] and they're going through headaches upon headaches in trying to get their information to their primary care docs"), veteran expectations about pain experience ("I think as a society we have shifted the focus to if this doctor doesn't relieve me of my pain I will find someone who does"), veteran knowledge and beliefs about various complementary non-pharmacologic approaches ("how many people know that tai chi will help with pain?… Probably none. I saw them doing tai chi down here at the VA clinic and the only reason I knew about it was because I saw it being done"), and access ("the only physical therapy I ever did… it helped…but it was a two-and-a-half-hour drive to get there three times a week… I can't do this"). Specific access barriers included local availability, time, distance, scheduling flexibility, enrollment, and reimbursement.

CONCLUSION: The veterans in this qualitative study expressed interest in using non-pharmacologic approaches to manage pain, but voiced complex multi-level barriers. Limitations of our study include that interviews were conducted only in five clinics and with seven female veterans. These limitations are minimized in that the clinics covered are diverse ranging to include urban, suburban, and rural residents. Future implementation efforts can learn from the veterans' voice to appropriately target veteran concerns and achieve more patient-centered pain care.

Topic: pain veterans pain management pharmacology

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

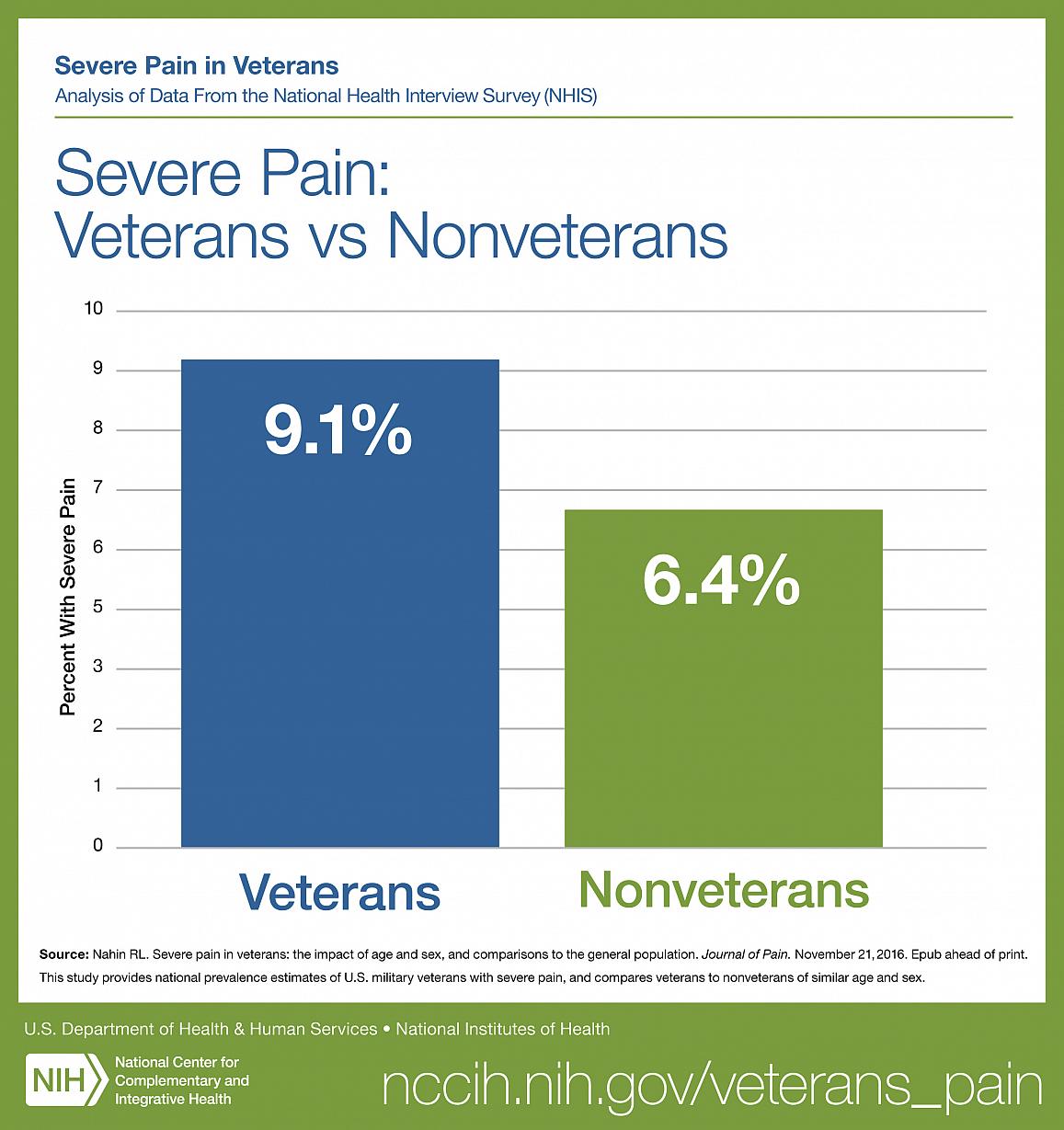

Pain is a longstanding and growing concern among US military veterans. Combined data from the 2010–2014 National Health Interview Survey indicated veterans under 70-yr old reported pain at a higher prevalence than non-veterans. Younger veterans aged 18- to 39-yr old had more than three times the odds of having severe pain, compared with older peers. [1] With approximately 30% of the American adult population affected by chronic pain, access to high-quality multidisciplinary treatment, including medications and complementary non-pharmacologic approaches, is a current public health priority. [2, 3] The most recent National Pain strategy called for increased access to multidisciplinary care and less reliance on medications as a singularly offered treatment for chronic pain. [4]

Given how common pain is among US military veterans, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has implemented the Veterans Choice Act (VCA) in April 2014, which bolstered longstanding efforts in improving pain management within the VA. [5] [Editors Note: The Veterans Choice Act has been eclipsed by the VA MISSION Act of 2018, which empowers veterans to seek care from community providers.]

To improve access to care that is not always available at specific VA facilities, the Act augments veterans’ access to community providers. By fiscal year 2016, the VA processed 18.9 million community care claims, many of which are pain-related and include non-pharmacologic approaches such as chiropractic care. Non-pharmacologic approaches are among the top six types of non-VA services sought by Veteran Choice Program users. [6]

Although several studies have assessed implementation to expand access to non-pharmacologic approaches for pain within the VA, to our knowledge, none have directly assessed veteran-perceived experiences. [7, 8] The current analysis aims to identify and understand veteran-perceived experiences with and barriers to complementary non-pharmacologic approaches for pain, adding the voices of veterans themselves to the literature. Very few other studies include the voice of veterans in regard to their experience of pain management. [9] A thorough understanding of veterans’ perceptions can inform patient-centered approaches for improving pain management in VA primary care

Methods

Approach

Data for this qualitative analysis were collected as part of the Effective Screening for Pain (ESP) study (2012–2017), a national randomized controlled trial (RCT) of pain screening and assessment methods. [10] This study was approved by the VA Central IRB and veteran participants signed written informed consent.

We recruited a convenience sample of US military veterans in five primary care clinics (four general clinics and one women’s health clinic), from three VA health care systems in California, Oregon, and Minneapolis, to participate in the ESP RCT. To be included, participants had to be military veterans who were waiting to see a provider for a visit where their vital signs, which includes RN documented “pain now,” would be documented. They also had to be capable of reading and answering questions rationally, for example, no obvious demonstration of cognitive impairment. Participants signed an informed consent. During initial recruitment, we asked veterans if they would be willing to participate in semi-structured phone interviews about pain care. From those recruited, they were not eligible to participate in interviews if they(1) had no working phone or

(2) were hearing impaired and unable to complete a phone survey.From the RCT sample, we recruited a convenience sample to participate in the interviews. We strategically over-sampled female respondents to ensure that their voice was represented, until they reached approximately 20% of the total interview group. Those who subsequently participated in interviews received a $30 voucher for the VA canteen store.

This analysis represents one piece of a larger evaluation effort using veteran interviews. Interviews occurred between January and March 2017 and lasted approximately 1 h (range 27–75 min). We used a semi-structured interview guide that elucidated patient perceptions of pain screening and assessment (e.g., risks, benefits, data, and process), and pain management and follow-up (e.g., care process; team involved; communication; coordination; challenges; management options including non-pharmacological approaches such ascognitive behavioral therapy [CBT],

exercise therapy,

massage,

mindfulness,

occupational therapy [OT],

physical therapy [PT],

Tai Chi, and yoga;

self-management;

treatment decision process; and

satisfaction with care).

[Editors Note: Isn't it curious that chiropractic care is not mentioned, or even considered in this report?]Veterans were also asked their gender, age, and current pain score on a numeric rating scale (e.g., what is your “pain now” on a scale of 0–10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable).

To encourage veterans to feel comfortable sharing their experiences and discuss sensitive issues, the investigators emphasized that all responses would be anonymous and presented in aggregate. Veterans were also explicitly told that there are no right or wrong answers and that answers would not be shared with their providers. All interviews were audio-recorded with veteran knowledge, professionally transcribed, and any identifying information was omitted. Transcripts were reviewed for accuracy.

For the ESP study, a code list for the veteran interviews was developed and iterated by three investigators via coding of five transcripts. In the larger evaluation, one high-level code “pain management” was applied to all transcripts; this included all references to pain management including medication, non-pharmacologic approaches, and self-management. All mentions of approaches other than medication including self-management and non-pharmacologic approaches (including CBT, exercise therapy, massage, mindfulness, occupational therapy [OT], physical therapy [PT], Tai Chi, and yoga) were then identified through manual review of all “pain management” output by one investigator.

A three-investigator team then evaluated transcribed statements relating to non-pharmacologic approaches using the method of constant comparison and produced five mutually agreed upon themes to describe veteran experiences. [11] The final list, of emergent themes, was then systematically applied to every mention of alternatives to medication. Secondary coders then reviewed each transcript for inconsistencies. Team meetings fostered consensus for code development and resolutions for coding discrepancies. All analyses used qualitative analytic software ATLAS.ti. [12]

Results

Table 1 We completed interviews with 36 veterans: 29 males and 7 females. They ranged in age from 28 to 94 yr and had pain scores ranging 0–9 on the NRS scale. Veteran experiences with accessing complementary non-pharmacologic approaches for pain clustered into five main themes: communication with provider about complementary non-pharmacologic approaches, care coordination, veteran expectations about pain experience, veteran knowledge and beliefs about various therapies, and accessing complementary non-pharmacologic approaches (Table 1).

Theme 1: Provider Communication About Alternative Pain Management Approaches

Veterans highlighted communication with providers about complementary non-pharmacologic approaches as a key factor to whether they tried or used alternative pain management approaches.

Veterans actively advocate for providers to communicate with them about alternatives to medication.“Every drug’s got side effects to it, and you want to know if you’re taking something else… how that’s going to interact with this pain killer… Just to minimize the amount that gets used and also if there are alternatives to it before it’s prescribed. So even if I’m in a lot of pain can we do some physical exercises? Can we get a new mattress because it’s painful at night? Get a new sofa because it’s painful when you sit or a new desk chair at work? Think about the alternatives before prescribing a real strong painkiller.”

[male veteran, Age 50-60, Pain now 2].One veteran even explained communication from a VA provider about pain and options for treatment as “one of the best things” the VA had ever given them.

“I’m 115 lbs., so every prescription that they gave me was way too powerful, made me drowsy. I was going through a really hard time in the last year of trying not to be homeless, so I was not willing to be on any drugs that kept me from being completely alert and able to think ahead and take care of myself., one of the best things the VA has ever given me was pain education and it was through my occupational therapist [I learned about non-pharmacologic approaches].”

[female veteran, Pain now 4].Just as good communication facilitated use of non-pharmacologic approaches, challenges with provider–patient communication can be a barrier to the uptake of complementary non-pharmacologic approaches. The challenges veterans identified included not being able to reach providers to discuss alternatives.

“He [Provider] said to me [Veteran], “We’ll go ahead and look at other alternatives and I’ll contact you.” And I was like, “All right, cool.” so I figured he’d probably research a few things and get back to me. Nope! …the ability to get a hold of the doctor is… a challenge.”

[male veteran, Age 30-40, Pain now 7-8].

Theme 2: Care Coordination for Alternative Pain Management Approaches

In contrast to Theme 1 in which veterans expressed positive and negative experiences in communication with providers, veterans generally had negative experiences with care coordination and offered many suggestions for improvement. Veterans faced challenges in coordinating pain care at multiple levels: between VA facilities, and between the VA and non-VA programs available in the community. One veteran with a painful condition gave an example of limited care coordination between two VA facilities in two different VA administrative areas.“I live in [area A]. So, before I wasn’t coming to [facility in area B] for primary care. I was going to [clinic in area A] which… doesn’t have the specialty care providers that I need [for complex painful condition]. They would still have to refer me to [large facility in area B-100 miles away]. So rather than deal with part of the regional difference between [facility in area A] and [facility in area B], I just decided to stick with one-stop shop… because all my specialty care is going to be there anyway… I have friends that go to small clinic in [area A] and I still see them down in [facility in area B] and they’re going through headaches upon headaches in trying to get their information to their primary care docs…”

[male veteran, Age 32, Pain now 7-8].Veterans also reported that despite the expanded treatment options offered by the Veterans Choice Program with regard to community care, challenges persisted with authorizations for accessing non-pharmacologic approaches in the community.

“Veterans Choice [program office] always calls me and says, “Hey, we’re setting up an appointment for you to go to this place and get physical therapy. You got an authorization in the system. We need to know what date and time works best for you”… so I tell them, “Hey, anytime is good, whenever you can get me in.” I don’t hear from them so I call… Veterans Choice is like… “We don’t show any authorizations or any appointments for you in the computer”… this happened to me many, many times now.”

[male veteran, Age 30-40, Pain now 2].

Theme 3: Veteran Expectations About Experiencing Pain

Veterans agreed that expectations of pain experience matter and even impact pain experience. For example, one veteran described that learning how pain “works” helped her have better expectations about and reactions to experiencing pain.“Just teaching me how the nerve system works, how the brain works, the pain signals, your new life with chronic pain. That has actually reduced my pain a little bit, just learning not to freak out every time I feel pain. It helps me to manage it better.”

[female veteran, Pain now 4].Veteran expectations vary in terms of pain management. Some veterans expect to live with some pain as opposed to being “pain free.” One veteran described how this expectation needs to be reset:

“There’s mental anguish. We believe as a society we should be inoculated from pain. We shield our kids from pain. We don’t want them to go through painful experiences. We have instant remedies for pain everywhere. Everything is pain-free. Right? Even filling out a form on the Internet, pain-free. You want to apply for a mortgage, pain-free. So, when we start talking about pain we have all kinds of messages coming to us about being free of pain … but we now have things like fibromyalgia and some strange things that are painful [where we have to accept some pain]”

[male veteran, Age 40-50, Pain now 2].Some veterans will change doctors when seeking the potentially unrealistic goal of being pain-free.

“I think as a society we have shifted the focus to if this doctor doesn’t relieve me of my pain [by prescribing medication I ask for] I will find someone who does, and that’s the doctor shopping phenomenon, right?”

[male veteran, Age 40-50, Pain score 2].Veterans also shared how cultural expectations regarding pain can inhibit seeking appropriate non-pharmacologic approaches. An African-American veteran demonstrates how cultural pressures dissuade her from seeking treatment for mental health dimensions of her pain:

“People will hide because of shame, because of what family members say, because of the way they were raised, because of societal image. It’s like it’s not okay to see a therapist, it’s not okay to see a psychiatrist. You’re not strong if you have to see a mental health professional, you know. I happen to be a black woman and one of the things that I used to hear growing up all the time, and even as a grown woman, “that’s for white people. White people go and lay on the couch and talk to a psychiatrist. Black women don’t do that. You suck it up”

[female veteran, Age 50-60, Pain score 9].

Theme 4: Veteran Knowledge and Beliefs About Alternative Pain Management Therapies

Veterans had a range of knowledge and beliefs about complementary non-pharmacologic approaches. Some veterans were aware of VA services for non-pharmacologic approaches, but others indicated not being aware that non-pharmacologic approaches are helpful for pain management.“I think yeah, for pain management, the best thing out there is word-of-mouth and educating people on it. How many people know that tai chi will help with pain?… Probably none. I saw them doing tai chi down here at the VA clinic and the only reason I knew about it was because I saw it being done. I had no idea.”

[male veteran, amputee with intermittent phantom pain, Pain now 0].Others demonstrated a lack of understanding that completing exercises at home was their responsibility and externalized the responsibility to their providers.

“I went to physical therapy for a while. Nobody ever followed up with me to ask me if I was continuing that physical therapy program… but if you’re going to have me do these exercises, I would expect that you would call me and make sure that I’m doing those exercises. Hold me accountable to it.”

[female veteran, Age 31, Pain now 7].

Theme 5: Access to Alternative Pain Management Therapies

Veterans identified access barriers to non-pharmacologic approaches that included availability. Here, one veteran describes only being offered transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) as an alternative to medication.“The only kind of non-pharmaceutical thing that they offer was that TENS unit… and I don’t want to give the perception that I’m seeking drugs because I’m not. (LAUGHS) …It’s just I feel like if I bring pain to the doctor, like they expect to think, yeah, here’s a pill, try this [so I don’t bring it up].”

[male veteran, Age 29, Pain now 3].Veterans highlighted their time as a potential barrier to considering complementary non-pharmacologic approaches. Veterans gave examples of the challenges of alternative therapy that requires multiple visits.

“I’m a consultant and I get paid by the hour when I’m onsite. So often times for me to go have a 20-min or 30-min PT session it costs me like $300 a day. So, when they say, “Oh, we’re going to prescribe PT two times a week or three times a week,” not only do I lose the money driving there, but then the waiting time, then the PT, and then driving back.”

[male veteran, Age 41, Pain now 1-2].Some veterans felt like some providers do not have time to consider complementary non-pharmacologic approaches.

“I’m [Veteran] going to find someone who will solve this [pain] because, obviously, you [provider] cannot. so often times doctors go, “Here, have a narcotic. Have a nice day.” And they have too much caseload to pay attention.”

[male veteran, Age 40-50, Pain now 7].Veterans explained how distance made certain treatments prohibitive. This veteran experienced relief doing physical therapy in a swimming pool, but could not continue with it because it was too far from home.

“They said you can try physical therapy, physical therapy helps. The only physical therapy I ever did and it helped some was basically in a swimming pool, but it was a two-and-a-half-hour drive to get there three times a week. Five hours round trip…I can’t do this.”

[male veteran, Age 68, Pain now 4].Veterans also indicated challenges with scheduling. One veteran describes losing his prescription to PT due to a mistakenly missed appointment, which caused him to give up on seeking PT as an option.

“There was a few times when I called ahead and said I couldn’t make it because I had meetings or whatever and I had canceled like a couple days in advance, they never cancelled my appointments, so then I got marked down as no-show for appointments and I got dropped from the program… They said… “you need to go get a new prescription for PT.” And I was like *** this.”

[male veteran, Age 40-50, Pain now 2].Veterans also indicated challenges with enrollment as a barrier to exercise therapy (e.g., pool/gym use).

“She [VA provider] put me in that program where you start exercising in the swimming pool. Then after I got out of that, I got access to the gym. Matter of fact, I’m going to ask her can she get me back in there, because my card expired and I can’t get back in there. Why do you need a card to go into the gym? A lot of people just like going to the gym and working out, that’ll do a lot of veterans good… you only get like a year on the card.”

[male veteran, Age 67, Pain now 0].Challenges with getting reimbursed for mileage for community appointments were also raised.

“You have to have them [community providers] set up a consult in the computer and the consult has to be in the computer before your appointment then you can file a travel voucher against it. Otherwise, the travel voucher gets kicked back as ineligible. And then you have the people over in the [VA] travel eligibility… that tell you, “Oh, it’s around 30 days.” I’m like, “No, it’s actually about 20 days,” or “No, it’s two weeks old.” And they’re like, “Oh, well, that’s just too much. You should have filed your travel voucher ahead of time.” “Well, no, you have 30 days. It’s still good, it can still be filed.” “Well, you should have filed it before.”

[male veteran, Age 30-40, Pain now 7].

Discussion

The veterans in our study raised multiple considerations for improving uptake of complementary non-pharmacologic approaches for pain. They noted that their use of non-pharmacologic approaches would be abetted by better communication with their providers, improved care coordination, and reduced access barriers. Veterans also highlight how the importance of education and communication in shaping knowledge, beliefs, and expectations about the course of pain and treatment options may also affect utilization of non-pharmacologic approaches.

Overall, our respondents wanted providers to offer non-pharmacologic approaches for pain. They are interested in both improved access to passive therapies that require in-person treatment as well as guidance on accommodations they can make to their life. Making recommendations about lifestyle changes such as changing mattresses or chairs may be outside the scope of what clinicians typically think to offer in primary care. Social work or therapist involvement to address home and lifestyle accommodations was recommended in the provider interviews collected in the ESP parent study. [8] Similarly, veteran results indicate that efforts to facilitate lifestyle changes might be helpful in reducing reliance on medications for pain management.

Historically, non-pharmacologic therapies for pain have not been widely available in US hospital facilities and their utility was less established in the scientific literature and not taught in medical school curriculum. [13, 14] In more recent years, the evidence for many non-pharmacologic approaches has expanded and now many patients and providers seek non-pharmacologic options for pain. [15–18] Individual providers, however, may have disparate understandings of the evidence and uses for non-pharmacologic approaches. [16, 19] The veterans in our study highlighted the fact that veterans also have varying knowledge and may not be aware of non-pharmacologic approaches local availability or potential helpfulness for pain.

Some veterans we interviewed did recognize the value of non-pharmacologic approaches but experienced frustration and multiple barriers to access. These barriers occurred at the patient, provider, and organizational levels. Specifically, many non-pharmacologic approaches (e.g., CBT, exercise therapy, massage, mindfulness, OT, PT, Tai Chi, and yoga) require multiple in-person appointments. This is in contrast to pharmacologic approaches where veterans can visit a facility intermittently or call into fill a prescription. Flexibility and accommodation are essential to make non-pharmacologic approaches that require multiple sessions a viable option. Specifically, veterans need appointments that accommodate their schedules as well as the flexibility to reschedule when work might interfere.

Programs such as the Veterans Choice Act have the potential to allow veterans to seek care closer to home. As the VA shifts toward being both provider and payer for community-based care, process improvements are needed to ensure the feasibility of accessing these external community-based appointments.

The challenges of care coordination serve as a reminder of how the complexity of pain as a condition is amplified by the complexity imposed by treatment. Veterans noted challenges based on geography; poor coordination can vitiate the seeming benefit of involving appropriate specialists. In order to receive care in the nearest facilities, veterans facing such a situation would need to enroll simultaneously in two regions. Our respondent had to un-enroll in his home region and re-enroll in a new one to see a primary care provider near home while receiving specialty care in the closest available medical center. As the VA is working to enhance access, simplifying care coordination between regional areas could improve the patient experience.

This study should be considered in light of the following limitations. First of all, the participants were sampled from only five clinics. These clinics, however, are diverse in that they serve a range of urban, suburban, and rural residents. Second, the VA population comprised only a small percentage of women, and our interview sample includes only seven female veterans. Due to the fact that our sample is not gender-balanced, we cannot make conclusive thematic comparisons. However, our data suggested that there may be differences between the male and female perspective in the emergent themes. We do consider it a strength that the study includes the voices of female veterans as it adds range to the perspectives we are able to represent.

Future analysis might comment further on the differences of perceptions of barriers between men and women. Third, due to the fact that this was a convenience sample, not all veterans interviewed had chronic pain. Because pain is a dynamic experience, and most veterans have experienced pain, veterans with low pain scores were still able to add valuable information about their expectations, experiences, and beliefs. Finally, we did not capture information about the type of pain or location of pain in the interviews and therefore cannot provide more descriptive patient characteristics. We include their pain score after their quote, not to reduce the individuals’ experience of pain to a number but to demonstrate that we capture the perspectives of veterans with diverse pain realities.

VA has been working to improve clinician and patient access to multidisciplinary, non-pharmacologic resources for pain (5). Veterans’ views further validate the importance of these efforts and inform health care providers of the need for additional steps including strengthening education and patient–provider communication about pain and expectations, providing information about availability and evidence for non-pharmacologic approaches including complementary and integrative health modalities, simplifying service delivery, and improving care coordination.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank R. Thomas Day, Holly Williams, Derek Vang, and Agnes Jenson for recruiting patients to the ESP study. We would also like to thank Jesse Holliday for scheduling phone interviews and acknowledge the other investigators on the greater ESP project team Erin Krebs, Peter Glassman, and Sangeeta Ahluwalia, whose intellectual contribution helped inform the development of this work. Finally, we would like to thank all the veterans who agreed to participate in our interviews.

Funding

Dr. Giannitrapani's and Mr. McCaa’s effort was funded by a locally initiated project granted by the Center for Innovation to Implementation (ci2i): Locally Initiated Project GIK0001134 (PI Giannitrapani). Data were collected as part of the Effective Screening for Pain study part of the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development CREATE program 13–020 (PI LORENZ). Dr. Timko was supported by VA HSR&D (RCS 00-001).

References:

Nahin, RL.

Severe Pain in Veterans: The Effect of Age and Sex,

and Comparisons With the General Population

J Pain 2017 (Mar); 18 (3): 247–254Kolodny A , Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. :

The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction.

Annu Rev Public Health 2015; 36: 559–74. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122957.Tsang A , Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. :

Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries:

gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders.

J Pain 2008; 9(10): 883–91.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health.

National Pain Strategy: A Comprehensive Population

Health-Level Strategy for Pain

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services,

National Institutes of Health; 2016.United States Department of Veterans Affairs :

Veterans Choice Program [cited 2017 07/01/2017]. Available from:

https://www.va.gov/opa/choiceact/Vanneman M

Optimizing Resources to Respond to the VA Access Crisis.

Academy Health Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA. 2017.Becker WC , Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L:

Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain.

BMC Fam Pract 2017; 18(1): 41.Giannitrapani K , Ahluwalia S, McCaa M, Pisciotta M, Dobscha S, Lorenz K:

Barriers to using nonpharmacological alternatives and reducing opioid use in primary care.

[cited 2017 October 23]. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx220.Matthias MS , Kukla M, McGuire AB, Bair MJ:

How do patients with chronic pain benefit from a peer-supported pain self-management intervention?

A qualitative investigation.

Pain Med 2016; 17(12): 2247–55.United States National Institutes of Health :

Clinical Trial: Effective Screening for Pain Study (ESP)

[cited 2017 July 01]. Available from:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01816763Glasser B , Strauss A:

The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research Aldine Transaction .

New Brunswick, NJ, 1967.ATLAS t.i: Version 7.

[computer program]. ATLAS.ti GmbH ; 2016.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575Eisenberg DM. Kessler RC. Foster C, et al.

Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use

New England Journal of Medicine 1993 (Jan 28); 328 (4): 246–252Baldwin CM , Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR:

A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and

alternative medicine: implications for integrated care.

Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(15): 1697–704.Fletcher CE , Mitchinson AR, Trumble EL, Hinshaw DB, Dusek JA:

Perceptions of other integrative health therapies by veterans with pain who are receiving massage.

J Rehabil Res Dev 2016; 53(1): 117.Kroesen K , Baldwin CM, Brooks AJ, Bell IR:

US military veterans’ perceptions of the conventional medical care system and their use of

complementary and alternative medicine.

Fam Pract 2002; 19(1): 57–64.McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D.

Use of Selected Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Treatments in Veterans with

Cancer or Chronic Pain: A Cross-sectional Survey

BMC Complement Altern Med 2006 (Oct 6); 6: 34Halpin SN , Perkins MM, Huang W:

Determining attitudes toward acupuncture: a focus on older U.S. veterans.

J Altern Complement Med 2014; 20(2): 118–22.

Return to VETERANS CARE

Return to NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Since 9-01-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |